Introduction

This chapter discusses various aspects of inflight maneuvers. It covers the standard burn, level flight, ascents and descents, maneuvering and lateral control, and contour flying. This chapter also includes information on chase crew management, landowner relations, and tethering.

The Standard Burn

To fly with precision, the balloon pilot needs to know how much heat is going into the envelope at any given time and how that heat affects the balloon’s performance. Balloon pilots have few outside sources, instruments, or gauges to help them fly. When a balloon pilot uses the burner, there is no direct way of knowing exactly how much lift is increased. Because there are few mechanical aids to help balloon pilots fly, some methodology must be devised to standardize a pilot’s input action, so the outcomes of those actions are predictable and the balloon is controllable. The standard burn is one way to gauge in advance the balloon’s reaction to the use of the burner. [Figure 7-1]

The standard burn is an attempt to calibrate the amount of heat being used, and is defined as a burn of four seconds. If each burn can be made identical, the balloon pilot can think and plan, in terms of number of burns, rather than just using random, variable amounts of heat with an unknown effect. The standard burn is based on using the blast valve or trigger valve found on most balloon burners. Some brands use a valve that requires only a fraction of an inch of movement between closed and open, and some require moving the blast valve handle 90°. While the amount of motion required to change the valve from fully closed to fully open varies, the principle remains the same—make each burn identical to another.

The inexperienced pilot should begin with the premise that the average balloon requires one standard burn of four seconds every 25 to 40 seconds in order to maintain level flight. Experience determines the exact length of time between burn intervals, and how other variables such as weight and ambient air temperature affect those intervals. The primary goal is to determine the rhythm of burns necessary to maintain level flight. All other maneuvers, then, become a departure from this point. The burn begins with the brisk, complete opening of the blast valve and ends with the brisk, complete closing of the valve at the end of the burn. During their training, some pilots count “one, one thousand; two, one thousand; three, one thousand; four, one thousand” to develop the timing.

The standard burn does not mean a burn that is standard between pilots, but rather, it is an attempt for the individual pilot to make all burns exactly the same length. The goal is not only to make each burn exactly the same length, but also to make each burn exactly the same. The pilot must open and close the valve exactly the same way each time. Most balloon burners were designed to operate with the blast valve fully open for short periods of time. When the blast valve is only partially opened, two things happen:

- The burner does not operate at full efficiency, and

- The pilot is not sure how much heat is being generated.

Burner Ratings

During any discussions of burner output, talk usually turns to the issue of “burner ratings”; that is, the amount of heat actually produced by a specific burner. Invariably, the talk turns into a “my burner is better than yours” type of exchange. In reality, there is virtually no difference between the burners produced by the major manufacturers and their respective output.

A pilot needs to understand the concept of British Thermal Units, or BTU, as a measurement of output. A BTU is defined as the quantity of heat required to raise the temperature of one pound of water by one degree Fahrenheit. While not particularly relevant to heating air, this has come to be a generally accepted form of measure for burner output. Of the four major manufacturers, three rate their burners at 18 to 19 million BTU output; the fourth at 43.9 million (with the caveat that that is produced at a supply line pressure of 200 PSI, well above the pressures that most balloonists use). A pilot needs to be aware that BTU output in a balloon burner equates to the amount of propane that is burned in an hour; BTU output is usually computed on this basis. Referring to the Propane Primer in Chapter 2, propane has a nominal value of 91,600 BTU per gallon under ideal circumstances. A simple mathematical calculation indicates that the average burner (a

18.5 million BTU rating) consumes approximately 202 gallons of fuel per hour. (18.5 million BTU divided by 91,600 BTU per gallon of propane = 201.96 gallons of fuel)

However, balloon burners are not used for an hour at a time; instead, they are used for very short periods of time, as discussed on page 7-2. If the numbers above are recalculated, it can be said that the standard burn of four seconds, as described in this section, puts approximately 5,139 BTU of heat into the balloon’s envelope. Remember, this is a theoretical statement of heat available, as no burner is 100 percent efficient.

There are numerous factors involved in burner design, such as volume backpressures, restrictions in the internal plumbing design, and more, all of which contribute to the final output rating. It is helpful to remember that the mathematics of burner design reveals the fact that output is a linear equation, when compared to pressure input; there is a direct correlation between the fuel line pressure and the burner’s output. This is not the case with the noise output of the burner, as the noise output increases exponentially as the pressure is increased. Reduction of burner noise represents the next hurdle in burner design; perhaps someday it will be possible to enjoy an almost silent balloon flight.

—Mark West and Martin Harns, Aerostar International, Inc.

Figure 7-1. Burner ratings and calculations.

A partially opened valve is producing a fraction of the heat available, but there is no way of knowing what the fraction is. [Figure 7-2]

Figure 7-2. Activated burner.

Another advantage of briskly opening and closing the valve is to minimize the presence of a yellow, soft flame. During inflation, for instance, a strong, narrow, pointed flame that goes into the mouth opening without overheating the mouth fabric or crew is desirable. A partial-throttle flame is wide and short and subject to distortion by wind or the inflation fan. If less than a full burn is desired, shorten the time the valve is open and not the amount the valve is open. Due to burner design (and the inefficiency of a partially opened valve), four 1-second burns do not produce as much heat as one 4-second burn.

If the mechanical aspects of flying can be learned, the systematic cadence can be converted into a rhythm that is smooth and polished. With practice, the rhythm becomes second nature and pilots fly with precision, without thinking about it. Using the standard burn, pilots can better predict the effect of each burn, minimize the potential danger of a burn to the envelope, and have a better flame pattern. The standard burn is referred to when discussing specific maneuvers.

Straight and Level Flight

Level flight, or equilibrium, is probably the most important of all flight maneuvers, as it serves as a baseline from which all other maneuvers are derived. A good pilot maintains level flight with a series of standard burns.

Level flight is achieved when lift exactly matches weight and the balloon neither ascends nor descends, but remains at one altitude. For every altitude, there is an equilibrium temperature. If a pilot is flying at 500 feet mean sea level (MSL) and wants to climb to 1,000 feet MSL, the balloon temperature must be increased. This is not only to attain equilibrium at the new (higher) altitude, but some excess temperature must also be created to overcome inertia and get the balloon moving.

Theoretically, if a pilot were to hold a hot air balloon at a constant temperature, the balloon would float at a constant altitude. However, there is no practical way to hold the envelope air temperature constant. Each time the pilot burns, the balloon tends to climb. The air in the envelope is always cooling and the balloon tends to descend. If the subsequent burns are perfectly timed, the balloon flies in a series of very shallow sine waves. [Figure 7-3, Line A] Of course, any variable changes the balloon flight. A heavier basket load, higher ambient temperature, or sunny day all require more fuel (by shortening the interval between burns) to maintain level flight.

In discussions of level flight, the terms “flying light” and “flying heavy” are sometimes used and bear explanation. A balloon is said to be “flying light” when the sine wave being described in the air is predominately on the high side of the desired altitude [Figure 7-3, Line B]. Many new or inexperienced pilots tend to fly light, and use the vent line in order to return to the desired altitude; this may create a situation where the pilot gets into a constant overcontrolling exercise and is best avoided. “Flying heavy” can be described as a scenario where the sine wave is predominately on the low side of the desired altitude [Figure 7-3, Line C]; if the balloon is left alone, it tends to fall. Flying heavy can be hazardous when contour flying. A balloon pilot must use all visual cues available and exercise a “finesse” type of control when contour flying (described later in this chapter).

Through experimentation, standards can be established that may be used as a basis for all flights. With practice and using the second hand of a wristwatch, a new pilot can fly almost level. The exercise of learning the pattern of burns (each day and hour is different) is an interesting training exercise, but not a practical real-life technique. The ability to hold a hot air balloon at a given altitude for any length of time is a skill that

Figure 7-3. Example of normal flight (Line A), flying light (Line B), and flying heavy (Line C).

comes only with serious practice. Unfortunately, most pilots do not spend enough time practicing level flight. During the practical test, given a choice of altitudes, it is easier to fly level at a lower altitude, due to the ease of acquiring visual references. However, the pilot must exercise care not to violate minimum safe altitude requirements (explained later in this chapter), and must be constantly alert for obstacles such as power lines in the flightpath.

Ascents and Descents

The temperature of the air inside the envelope controls balloon altitude. A balloon that is neither ascending nor descending is in equilibrium. To cause the balloon to ascend, increase the temperature of the air inside the envelope. If the temperature is increased just a little, the balloon seeks an altitude only a little higher and/or climb at a very slow rate. If the temperature is increased significantly, the balloon seeks a much higher altitude and/or climbs faster. If the balloon is allowed to cool or hot air is vented, the balloon descends.

Even without the input action by the pilot, it must be remembered that the air inside the envelope is dynamic. The air mass is constantly moving within the confines of the envelope, attempting to seek a level of equalization. While it varies with each envelope, input action by the balloon pilot can take from 6 to 15 seconds to be realized as a reaction by the balloon. Planning the maneuver, anticipating the reaction time, inputting the proper burn, and observing the reaction must result in smooth and natural movement by the pilot.

Ascents

Using evenly spaced, identical standard burns to fly level, a pilot needs to make only two consecutive burns to have added excess heat to make the balloon climb. For example, if the pilot can maintain level flight with a standard burn every 35 seconds, and then makes two burns in succession instead of one, the balloon has an extra burn and climbs. How fast the balloon climbs depends on how much extra heat has been added. Under nominal conditions, if the standard burn has been made to hold the balloon at level flight and a second burn is within a few seconds (not waiting the 35 seconds), the average balloon starts a slow climb. Three consecutive burns results in a faster climb.

Once the desired climb rate is established, return to the level flight routine to hold the balloon at that rate. The higher the altitude, or the faster the rate of climb, the shorter the interval between burns. In an average size balloon (usually a 77, 000 or 90,000 cubic foot envelope) at 5,000 feet, the pilot may be required to make a standard burn every 15 to 20 seconds to keep the balloon climbing at 500 feet per minute (fpm). At sea level, the same rate may require burning only every 30 to 40 seconds. Burn rates cannot be predicted in advance, but practice provides a basis to begin with and experimentation finds the correct burn rate for a particular day’s ambient temperature, altitude, envelope size, and balloon weight.

Another skill to develop in ascents is knowing when to stop burning so the balloon will slow and level at the chosen altitude. The transition from a climbing mode to level flight involves estimating the momentum and coasting up to the desired or assigned altitude. One methodology is illustrated in Figure 7-4. During this flight, the pilot has decided to leave his current altitude (A) and climb to another (C). While climbing, the pilot adjusts burn times to be at a 100 fpm rate of climb by the time he or she is at a point 100 feet below the desired altitude (B). Under most circumstances, the balloon “coasts” the additional 100 feet and rounds out, or resumes level flight, at the desired altitude. It may be necessary to use the vent for a short time to stop the ascent with caution not to vent excessively, thereby causing the balloon to go into a descent. The balloon pilot must remember that each manufacturer has a specific interval that the vent can be opened while in flight. Should that interval be exceeded, it can have a disastrous result. With practice and application, the pilot can learn this skill without the use of the vent, not only conserving fuel, but also flying a much more controlled flight. Generally, to achieve a smooth transition to the new altitude, the rate of ascent should not exceed the distance to the new altitude. For example, if the balloon pilot is 500 feet below the desired new altitude, the rate of climb should not exceed 500 fpm. When the pilot is 300 feet below the desired altitude, the rate of climb should not exceed 300 fpm. An ascent of 200 to 300 fpm is slow enough to detect wind changes at different altitudes, which is helpful in maneuvering. Above 500 fpm, it is possible to fly through small, narrow wind bands or wind with very small direction changes without noticing. It is a good idea to launch and climb at a slow speed (100 to 200 fpm) to make an early decision regarding which direction to fly.

Figure 7-4. Ascent schematic.

Descents

The only direct control of the balloon the pilot has is vertical motion; the pilot can make the balloon go up by adding heat. Therefore, the pilot can make it come down by venting or not adding heat. For horizontal or lateral motion, a balloon pilot must rely on wind, which may or may not be going in the desired direction. A good pilot learns to control vertical motion precisely and variably for maximum lateral choice.

To start a descent from level flight, skip one burn, and then return to the level flight regimen to hold the descent at a constant rate. Alternatively, hot air balloons are equipped with a vent. When opened, the vent releases hot air from the envelope and draws cooler air in at the mouth, thus reducing the overall temperature and allowing the balloon to descend. A pilot should learn to calibrate the use of the vent, as well as the burners, and know how much air is being released in order to know what effect to expect. For predictability, time the vent openings and open the vent precisely. Parachute vent balloons usually have a manufacturer’s limitation on how long the vent may be open. Use the vent sparingly; it should not be used instead of patience, unless a rapid change in altitude is needed.

Figure 7-5. Descent schematic.

A new pilot can learn the classic balloon flare by matching the vertical speed indicator (VSI) to the altimeter, i.e., descend 500 fpm from 500 feet above ground level (AGL), 400 fpm from 400 feet AGL. Below 200 feet, a pilot should not use instruments, but look below for obstacles, especially power lines. This maneuver is illustrated in Figure 7-5. Departing from the altitude indicated at “A,” the pilot allows the balloon to start a descent. During the descent, the pilot maintains a reasonable rate of descent, slowing to a rate of 200 fpm at

B. By the time the balloon reaches C, the pilot should have a rate of descent of 100 fpm, and by using one or two standard burns, should be able to level off (“round out”) at the desired new altitude.

Rapid/Steep Descents

A rapid, or steep, descent in a balloon is a relative term. A 700 fpm descent started at 3,000 feet AGL is not necessarily rapid; however, if started at 300 feet AGL, it is rapid and may be critical. Rapid descents should be made with adequate ground clearance and distance from obstacles.

To execute a steep descent, the balloon pilot must be well aware of the balloon’s response times and have sufficient altitude for the maneuver. In Figure 7-6, the pilot has initiated a steep descent at Point A. For this discussion, assume that altitude is 1,500′ AGL. The descent may be initiated either through the use of the vent or by holding two or three burns. By the time the balloon reaches the point indicated at B, it may be descending in excess of 500 fpm; the pilot should make a standard burn at this point, as the air passing over the envelope fabric accelerates cooling. A standard burn ensures that the balloon maintains a temperature sufficient to keep it under control throughout the maneuver. This burn should not slow the descent.

At a point halfway between the ground and the previous burn [Figure 7-6, Point C], the pilot should make a long (twice standard length) burn; if there is no reaction from the balloon, then the pilot should do another burn. Immediately upon sensing a reaction from the balloon, the pilot should stop the burn and allow the balloon to descend to a proper pullout altitude. [Figure 7-6, Point D] If done properly, the deceleration burns stops the balloon’s descent just above the desired altitude or the ground. This maneuver requires experience and practice; timing is critical.

During the initial stages of learning this maneuver, the pilot should set a “floor” (altitude lower limit) to practice with.

Figure 7-6. Steep descent schematic (not to scale).

As the pilot gains more skill, as well as confidence, that “floor” may be lowered until the pilot is able to execute the maneuver to ground level.

Maneuvering

The art of controlling the horizontal (lateral) direction of a free balloon is the highest demonstration of ballooning skill. The balloon is officially a nonsteerable aircraft. Despite the fact that balloons are nonsteerable, some pilots seem to be able to steer their balloons better than others. Being knowledgeable of the wind at various altitudes, both before launch and during flight, is the key factor for maneuvering.

Maneuvering, or steering, comes indirectly from varying one’s time at different altitudes and different wind directions. The pilot must have knowledge of the winds at different levels, as previously discussed in Chapter 3, Preflight Planning, as well as being able to determine the balloon’s direction in flight.

Winds Below

When in flight, winds below can be observed in many ways. Observe smoke, trees, dust, flags, and especially ponds and lakes to see what the wind is doing on the ground. To determine what is happening between the balloon and the ground, watch other balloons, if any.

Another means of checking winds below is to drop a very light object and watch it descend to the ground. However, exercise caution with this method. Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations (14 CFR) part 91 allows objects to be dropped from the air that will not harm anything below. 14 CFR section 91.15, Dropping Objects, states “No pilot in command of a civil aircraft may allow any object to be dropped from that aircraft in flight that creates a hazard to persons or property. However, this section does not prohibit the dropping of any object if reasonable precautions are taken to avoid injury or damage to persons or property.”

Some items that may dropped without creating a hazard are small, air-filled toy balloons, small balls made of a single piece of tissue, or a small glob of shaving cream from an aerosol can. A facial tissue, about 8″ x 8″, rolled into a sphere about the size of a ping-pong ball works well. These balls fall at about 350 fpm, can be seen for several hundred feet, and are convenient to carry. Counting as the tissue ball descends, a pilot can estimate the heights of wind changes by comparing times to the ground with the altimeter reading. Experiment by dropping some of these objects, practice reading the indications, and plan accordingly.

Direction

There are several methods of accurately determining the balloon’s direction at any given moment, particularly with the advent of low-cost hand-held global positioning system (GPS) units. However, the pilot should be familiar with “old-school” methods, as GPS units break or fall overboard, and batteries fail.

The pilot should first be positioned in the front of the basket, relative to the direction of flight. Then, the pilot should create a “sight picture,” using part of the basket’s superstructure, making an allowance for any possible spin of the basket, and then select a landmark along the route of flight. This process takes a few seconds if the landmark does not change position in relation to the “sight picture.” Then, the line that may be drawn between the balloon’s current position and the selected landmark is the ground track of the balloon. It is important that the pilot maintain a constant altitude while performing this evaluation; any change in altitude may put the balloon into a different wind flow, which requires the evaluation to be performed again.

It can be helpful to carry a magnetic sighting compass on the flight. Identifying the bearings to a couple of distant landmarks and comparing this to the ground track can provide useful information to the balloon pilot.

Examine Figure 3-12 in Chapter 3. If the pilot can make the mental extrapolation between known wind directions at different altitudes and the desired direction of travel, maneuvering the balloon becomes a simple exercise in direct control, that is, vertical movement.

Contour Flying

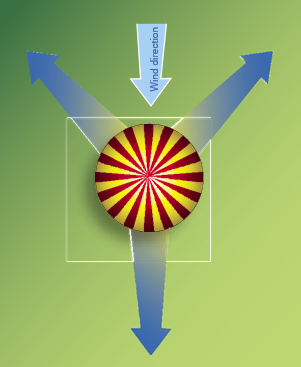

Contour flying may be the most fun and most challenging, but, at the same time, may also be the most hazardous and misunderstood of all balloon flight maneuvers. A good definition of contour flying is flying safely at low altitude, while obeying all regulations, considering persons, animals, and property on the ground. Safe contour flying means never creating a hazard to persons in the basket or on the ground, or to any property, including the balloon. [Figure 7-7]

At first glance, the definition is subjective. One person’s hazard may be another person’s fun. For instance, a person who has never seen a balloon before may think a basket touching the surface of a lake is dangerous, while the pilot may think a splash-and-dash is fun.

Minimum Safe Altitude Requirements

Legal contour flying has a precise definition. While the FAA has not specifically defined contour, it has specified exactly what minimum safe altitudes are. 14 CFR part 91, section 91.119, refers to three different areas: anywhere, over congested areas, and over other than congested areas, including open water and sparsely populated areas.

More balloonists are issued FAA violations for low flying than for any other reason. Many pilots do not understand the minimum safe altitude regulation. Many balloonists believe the regulation was written for heavier-than-air aircraft and that it does not apply to balloons. That is a false belief; the regulation was written to protect persons and property on the ground and it applies to all aircraft, including balloons. Since this regulation is so important to balloonists, the following is the applicable portion of 14 CFR part 91, section 91.119—Minimum safe altitudes: General.

“Except when necessary for takeoff or landing, no person may operate an aircraft below the following altitudes:

- Anywhere. An altitude allowing, if a power unit fails, an emergency landing without undue hazard to persons or property on the surface.

- Over congested areas. Over any congested area of a city, town, or settlement, or over any open air assembly of persons, an altitude of 1,000 feet above the highest obstacle within a horizontal radius of 2,000 feet of the aircraft.

Figure 7-7. Contour flying.

- Over other than congested areas. An altitude of 500 feet above the surface, except over open water or sparsely populated areas. In those cases, the aircraft may not be operated closer than 500 feet to any person, vessel, vehicle, or structure.”

14 CFR part 91, section 91.119(a) requires a pilot to fly at an altitude that allows for a power unit failure and/or an emergency landing without undo hazards to persons or property. All aircraft should be operated so as to be safe, even in worst-case conditions. Every good pilot is always thinking “what if…,” and should operate accordingly. This portion of the regulation can be applied in the following way. When climbing over an obstacle, a pilot can make the balloon just clear the obstacle, fly over it with room to spare, or give the obstacle sufficient clearance to account for a problem or miscalculation. An obstacle can be overflown while climbing, descending, or in level flight. Descending over an obstacle gives the greatest opportunity to misjudge clearance over an obstacle. In level flight, the danger is reduced. Hazards are minimized by climbing. Most instructors teach minimizing the hazard by climbing when approaching an obstacle, thus giving room to coast over the obstacle in case of a burner malfunction.

14 CFR part 91, section 91.119(b) concerns flying over congested areas, such as settlements, towns, cities, and gatherings of people. There is no standard definition of “congested area” or “open air assembly of persons” but case law has indicated that a subdivision or homes, constitute a congested area, as does a small rural town.

A balloon pilot must stay 1,000 feet above the highest obstacle within a 2,000-foot radius of the balloon. This is a straightforward regulation and easy to understand. Note that the highest obstacle is probably an antenna, tower, or some other tall object, not the rooftops. Two thousand feet is almost one-half mile. This portion of the regulation is often forgotten or ignored. [Figure 7-8]

A conscientious pilot includes livestock of any form—dairy cows, horses, poultry—in the 1,000-feet above rule. Domestic animals, while not specifically mentioned in the regulations, are considered to be property; and experienced pilots know that almost all poultry, exotic birds, swine, horses, and cows may be spooked by the overflight of a balloon. Livestock in large fields seem to be less bothered by balloons; however, it is always a good idea to stay at least 1,000 feet away from domestic animals. This is discussed in detail on page 7-16.

Figure 7-8 Minimum safe altitudes over a congested area

14 CFR part 91, section 91.119(c) refers to two area types: sparsely populated and unpopulated. Here, the pilot must stay at least 500 feet away from persons, vehicles, vessels, and structures. “Away from” is the key to understanding this rule. The regulation specifies how high above the ground the pilot must be and also states the pilot may never operate closer than 500 feet. There exists a possibility for misunderstanding in interpreting the difference between congested and other than congested, as neither of these terms are defined by the FAA regulations. As an example, operating below 1,000 feet AGL within 2,000 feet of a congested area is in violation of 14 CFR part 91, section 91.119(b), even though the bordering area may be used only for agricultural purposes. Therefore, when flying over unpopulated land near a housing tract, the balloon must fly either above 1,000 feet AGL or be 2,000 feet away from the houses.

To stay 500 feet away from an isolated farmhouse, imagine a 1,000-foot diameter clear hemisphere centered over the building. [Figure 7-9] If the balloon is 400 feet away from the structure on the horizontal plane, the balloon pilot only need fly about 300 feet AGL to be 500 feet away from it. If the balloon passes directly over the building, then there must be a minimum of 500 feet above the rooftop, chimney, or television antenna to be legal.

In summary, regulations require:

- Flying high enough to be safe if a problem occurs;

- 1,000 feet above the highest obstacle within a 2,000- foot radius above a congested area; and

- An altitude of 500 feet above the surface, except over open water or sparsely populated areas.

Figure 7-9 Minimum safe altitude over a sparsely populated area

In those cases, the balloon may not be operated closer than 500 feet to any person, vessel, vehicle, or structure. This is an easy to understand regulation that requires compliance from all pilots.

Contour Flying Techniques

Aside from the legal aspects, contour flying is probably the most difficult flying to perform. The balloon pilot must see all obstacles on or near the balloon path, remember their location, and maintain situational and spatial awareness. Terrain or obstacle height must be estimated and allowed for, and the pilot must always be prepared for an unexpected situation. A relationship must be established between the balloon altitude and the terrain or obstacle height. All these mental calculations must occur in a few seconds, in a continuous cycle, as the pilot executes a complicated flight profile.

The balloon practical test standards (PTS) asks the applicant to demonstrate contour flying by using all flight controls properly to maintain the desired altitude based on the appropriate clearance over terrain and obstacles, consistent with safety. The pilot must consider the effects of wind gusts, wind shear, thermal activity and orographic conditions, and allow adequate clearance for livestock and other animals.

Since most contour flying is done in unpopulated areas, the balloon is rarely higher than 300 feet AGL and frequently much lower; therefore, the balloon’s flight instruments are seldom observed. Because mechanical instruments have several seconds lag and electronic instruments are very sensitive, pilots must rely on their observation and judgment.

When flying at low altitude, the pilot must be vigilant for obstacles, especially powerlines and traffic, and not rely solely on instruments inside the basket. The pilot should always face the direction of travel, especially at low altitude. The pilot’s feet and shoulders should be facing forward. The pilot should turn only his or her head from side to side (not the entire body) to gauge altitude and to detect or confirm climbs and descents. Facing the direction of flight cannot be overemphasized; there are many National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) and FAA accident reports describing balloon contacts with ground obstacles because the pilot was looking in another direction.

Contour flying requires somewhat shorter burns than the standard burn. To fly at low altitudes requires half or quarter burns. One disadvantage in using small burns is the possibility of losing track of the heat being created. Precise altitude control requires special burner techniques. Another hazard of a series of too small burns is the accumulation of added heat before the effects of the last burn have been evaluated. The balloon actually responds to a burn 6 to 15 seconds after the burner is used.

One technique to determine if the balloon is ascending, flying level, or descending is to sight potential obstacles in the flightpath of the balloon, such as the power lines shown in Figure 7-10. As the balloon approaches the wires, the pilot should determine how the wires (or other obstacles) are moving in his or her field of vision relative to the background. If they are moving up in the pilot’s field of vision (shown by the red arrow), or staying stationary, then the balloon is on a descent that may place the pilot and passengers at risk. Conversely, if the wires are moving down in the pilot’s field of vision (as indicated by the green arrow), then the balloon is either in level flight or ascending, and able to clear the obstacle.

Figure 7-10 The movement of the power lines either up or down in the pilot’s field of vision can indicate whether or not the balloon has sufficient obstacle clearance.

Some favorite sighting objects are a power pole as the near object and the line of a road, field, or orchard as the far object—lines may be observed moving up and down the poles. Water towers with checkerboard or striped markings are also good sighting objects. Vigilance is required for constant scanning of the terrain along the flightpath, and the pilot must be alert to avoid becoming fixated on sighting objects. Again, the pilot should look where he or she is going, not where he or she has been. When flying in proximity to other balloons, particularly at lower altitudes, it is easy to become fixated on the other balloon(s) and attempt to follow their lead. The balloon pilot should remember to fly his or her balloon and let the other pilots fly theirs.

The particular pleasures of contour flying can best be enjoyed in a balloon. It is wonderful to fly at low level over the trees, drop down behind an orchard, float across a pond just off the water, watch jackrabbits scatter—see sights up close. No other aircraft can perform low level contour flying as safely as in a balloon, and in no other aircraft is the flight as beautiful. Contour flying can be great fun, but remember that the balloon should always be flown at legal, safe, and considerate altitudes.

Contour Flying Cautions—Aborted Landings

The line between contour flying and unsafe, inconsiderate, and misunderstood practices can sometimes be very fine. Observers often misinterpret aborted landings on the ground as buzzing or rude flying. Sometimes landing sites seem to be elusive. A typical situation is the pilot descending to land at an appropriate site, but miscalculating the winds below and the balloon turns away from the open field toward a farmhouse. The farmer sees the balloon descend, turn towards the house, and, with noisy burners roaring, zoom back into the air and proceed. The pilot was not being rude or inconsiderate, just inexperienced. The pilot did not mean to swoop down to buzz the house; the wind had changed. If the pilot had watched something drop from the basket to gauge the winds below or been more observant, the pilot would have known the balloon would turn towards the house as it descended. A squirt of shaving foam from an aerosol can or a small piece of rolled up tissue could have alerted the pilot of the different wind at lower altitudes.

Two or three of these swoops over a sparsely populated area, and people on the ground may not only think the pilot is buzzing houses, some people may think the pilot is having a problem and is in trouble. That is when the well-meaning landowner calls the police to report a “balloon in trouble.” Flying too close to a house (a friend’s house, for example) to say hello, dragging the field, or giving people a thrill by flying too low over a gathering are examples of buzzing, which is illegal and can be hazardous.

Use of Instruments

14 CFR part 31 and the balloon manufacturers’ equipment lists specify certain instruments to be in the balloon. However, most pilots find they use instruments less and less as they gain experience and familiarity with the balloon.

For instance, while the VSI and the altimeter can be used to execute a smooth descent and transition to level flight, the experienced pilot refers only occasionally to the instruments during maneuvers. This is especially so in maneuvers involving descents where more reliance is placed on sight pictures and visual references.

Some beginner pilots become fixated on the instruments and forget to scan outside for obstacles. If a pilot spends too much time looking at the flight instruments, the instructor may cover the instrument pack with a spare glove or a hand to try to break the formation of a bad habit. Instruments are required and useful, but should not distract the pilot from obstacle avoidance. Always practice see-and-avoid.

InFlight Emergencies

An emergency is a sudden, unexpected situation or occurrence that requires immediate action. In aviation, an emergency is a critical, possibly life-threatening or property- threatening occurrence that may require outside assistance. In an emergency, the pilot may violate any regulation as necessary to safely resolve the emergency, but must be prepared to justify his or her actions.

Because of its basic simplicity, there are few catastrophic failures or emergencies in a hot air balloon. Virtually all emergency situations involving balloons can be grouped into three categories:

- Loss/malfunction of vent or deflation line

- Loss/malfunction of pilot light

- Fuel leak

Loss/Malfunction of Vent or Deflation Line

This is usually thought of as a loss of the envelope valve control line. This could occur after a particularly windy inflation, during which the pilot has inadvertently burned through the control line and failed to notice it prior to launch. Another variation could be a control line stuck in a guide pulley, preventing the pilot from being able to control the parachute vent.

Regardless of the reason, loss of a control line must be handled. A pilot experiencing this problem must be prepared to land the balloon with a minimal amount of control, as he or she has use only of the burner to affect the descent. The pilot should maintain minimum altitudes and land in the largest area possible. If a high wind landing is expected, the pilot should anticipate rebound and dragging after touchdown; the pilot also needs to consider the prospect of deliberately landing the balloon in a less than desirable area in order to avoid potential power line contacts.

Loss/Malfunction of Pilot Light

Hot air balloon burner pilot lights are extremely reliable; however, they do fail at times. This is usually caused by a failure in the valve controlling the pilot light, or clogging of the orifice in the pilot regulator due to contamination in the fuel supplying the pilot light.

In a dual burner system, the failure of a pilot light is not a serious issue, as the balloon can still be controlled through the use of the second burner. The pilot may attempt to relight the pilot light by using both burners at the same time. To some extent, the pilot may be able to utilize this procedure to fly the balloon until able to land in a suitable location, should the extinguished pilot light not relight.

Pilot light failure in a single burner balloon is of more concern, as the pilot’s options for continued flight are reduced. The pilot needs to take immediate action to relight the pilot light, either through the use of a piezoelectric igniter (if equipped), or by using a striker or other ignition source. Many balloon burners are not designed to be conveniently relit while standing in the basket; this should be practiced on a periodic basis by the pilot, at a minimum during flight reviews. Should the pilot light not relight immediately, many burners can still be utilized by “cracking” the main blast valve very slightly, and then lighting the fuel stream from the burner’s jets. Other sources may include the backup system fitted in that particular balloon. The pilot may slightly open the valve controlling the backup system, and attempt to light that stream of propane. In any case, a landing as soon as practical is probably the best course of action

Fuel Leak

Fuel leaks in flight have the potential for catastrophic results and must be acted upon immediately. Because of the design of most balloon fuel systems, there are numerous potential “leak points” which may be the source for a fuel leak. Fuel lines and fuel line fittings, tank valves, and blast valves all have the potential for failure, and the balloon pilot must be aware of the various circumstances, and be prepared to deal with them.

Virtually all in-flight fuel leak emergencies in a balloon can be dealt with by shutting off the fuel source. Small fires from leaks around a fuel line fitting may be extinguished by shutting off the fuel source and then wrapping a gloved hand around the fitting and “snuffing” out the flame before it can spread further.

Because of the variety of systems, valve types, and differences in operations, a pilot should review the flight manual for his or her particular balloon system, and be familiar with and regularly practice the emergency procedures. The previously listed information is general in nature, and is not specific to any particular type of balloon, nor should it be taken as a specific procedure to be followed in the event of an in-flight emergency. In all cases, the information contained in the manufacturer’s flight manual should be followed.

In all emergencies, it is imperative that the pilot maintain control of the balloon. Many minor problems can quickly become major problems if the pilot fails to continue to fly the balloon. Additionally, the use of a checklist for in-flight emergencies is not appropriate. First, the pilot must resolve the situation, and then refer to an appropriate checklist or the balloon’s flight manual to verify the appropriate action.

Tethering/Mooring

Tethering a hot air balloon, despite its apparent simplicity, is perhaps the most demanding and stressful operation in ballooning, both in terms of equipment and the pilot. Balloons are designed to be free flown, not tied to the ground, and tethering incurs forces on a balloon that can, under certain circumstances, exceed design limits. The pilot conducting a tether is often called upon to conduct two or three hours of precise, “finesse” flying, which many times he or she is not prepared for. The crew must endure 2 to 3 hours of non- stop handling to manage this complex and often exhausting operation. Safe conditions fall within narrow ranges and a safe tether often demands more attention and management than flying in marginal conditions.

Every tether situation is unique enough to require tailoring the operation to specific needs and equipment. However, the idea of a “simple” tether should not lure the pilot into underestimating the very real demands and risks that come with it. A skilled and knowledgeable crew allows a pilot to take advantage of the many benefits tethering offers. Under suitable conditions, a well planned multi-hour commercial tether can last for hours, reach a media audience of millions, and offer several hundred people their first brief balloon ride. Regardless of the reasons for tethering a balloon, all forms of tethering require the same basic preparations and guidelines for safety.

The balloon pilot contemplating a tether operation should remember that the requirements of 14 CFR Part 91, General Operating and Flight Rules, apply to all operations conducted with a type-certified hot air balloon. There is a popular misconception that tether operations are conducted under the provisions of 14 CFR Part 101, Applicability; this is an incorrect assumption. Tether operations must be conducted by a certificated pilot, and may not, under any circumstances, be performed by an individual not in possession of an airman’s certificate.

Laying out the balloon for a properly executed tether operation requires a little more preparation than a normal launch layout. Initial planning needs to take into consideration the winds, both current and forecast, for the period of time the tether is to be conducted. The tether site should be at least twice, and preferably three times, the size of a normal launch area for that particular balloon. It may be surrounded by trees, buildings, and other obstacles. Under certain circumstances, this may work to the pilot’s advantage, as these may block low-level, lower velocity winds. Higher winds may create turbulence that significantly affects the balloon. [Figure 7-11]

There are two primary methods of tethering, the three-line method and the six-line method. In the three-line method, lateral lines are attached at the top of the basket, generally to the suspension of the balloon, to transfer stress loads from the balloon directly to the lateral lines, and not through the basket’s superstructure. In the six-line method, three vertical “bridle” lines are connected from the top of the balloon to the top of the basket’s superstructure and three additional lines

Figure 7-11 Layout schematic for a balloon tether.

(laterals) are attached to the vertical bridles. [Figure 7-12] The six-line system is preferable in windier conditions, as it allows the balloon to move within the framework created by the bridles and laterals, but keeps the balloon upright and confined to a relatively small area. The specific setup required is dependent on the intent of the tether and whether rides are being offered.

In almost all cases, the manufacturer’s flight manual specifies procedures and techniques for tethering the balloon, and the prudent pilot is aware of these instructions and possible limitations prior to conducting a tether.

Tether safety often depends more on flight team skills and preparation than anything else. The following tethering safety tips are drawn from the book, Hot Air Balloon Crewing Essentials, by Gordon Schwontkowski, and is an excellent reference text for balloon pilots as well as crew.

- Whether you use a commercially available tether system or your own quality ropes matters less than how well and how thoroughly you prepare. Securely attach two or three tether lines minimum to load rings, envelope carabiners, or other brand specific point on your equipment.

- Triangulated wind protection is the goal. Attach tether lines to secure objects such as parked vehicles so that two lines always distribute wind loads. This protects you on all sides from turbulence and potential downdrafts from buildings.

- Focus! Constantly watch weather conditions and line tensions for changes or needed adjustments. Listen to the crew for feedback and instruction. Direct spectators and participants according to your needs and their safety rather than chatting with them.

- Note and adjust for weather changes. Weather places great unnatural stresses on tethered balloons. Be prepared to suspend or cancel a tether at any moment due to changing weather. Allow extra time for packing lines and other tether equipment when considering whether to shut down.

- Plan for any one line to fail or come untied with no notice. Create a backup plan you can implement immediately to maintain control and safety.

- Watch for spectators and children who want to hang onto tether lines and ride them off the ground. Keep all noncrew away from lines; suddenly tight or rising lines pose risks for all concerned. At NO TIME should any crew member ever leave the ground (riding or hanging on the basket, holding ropes, etc.).

- Devote one crew member exclusively to organizing passengers in a line far back from the balloon and tether lines. Select groups by number, weight, age, or an appropriate combination of factors.

- Adding weight is necessary on landing and during passenger switches, giving many opportunities for someone’s toes or a foot to slip beneath a fully loaded basket. Keep everyone similarly clear of lines running to the basket or lower envelope.

- Inspect lines frequently to ensure they are attached securely at both ends, particularly under heavy loads or in stronger wind conditions.

Figure 7-12 A six-line tether.

Inflight Crew Management

The balloon chase crew does much more during the flight than merely drive and wait for the balloon to land. As an integral part of the flight team, the crew can often have a significant impact on flight safety. Rather than passively follow behind the balloon’s perceived route, a knowledgeable chase crew can assist in the execution of the flight and play a large role in flight safety and management.

Immediately after the launch, the crew should promptly load equipment and prepare to leave the launch field. At a large fun fly of local pilots, or perhaps a competitive event, there may be a temptation for the crew to remain on the field and socialize; a crew on the field is of little or no use to a pilot who may be in difficulty. The crew chief, in conjunction with the pilot, should have a planned route off the launch site and a methodology for conducting the chase. Some pilots prefer for the chase crew to be ahead of the balloon, while other pilots have the chase crew follow the balloon throughout the entire flight. This is a matter of personal preference and may have an impact on the comfort level of the pilot. Either way is acceptable, as long as the pilot and crew remain in contact, and there is a plan in place for the eventual recovery of the balloon.

Chasing the balloon is, at times, grossly oversimplified. The crew should always bear in mind that they may have to plan on how to be in one of two places at any given moment: where the balloon currently is and where it appears to be heading in the next few minutes. A good rule during the first half of the planned flight is to leapfrog ahead of the balloon, let the balloon catch up, and then repeat the process. Even in familiar flying areas, the crew should frequently check maps to determine the flightpath, likely landing areas, and the best routes to get there. The crew must constantly be aware of changing conditions that may affect the flight; winds increasing, decreasing, or changing directions, or perhaps traffic situations that affect how the crew gets to the balloon after landing.

Crew Behavior

During the chase, the crew should remember to drive legally and politely. Driving at high rates of speed with no justification creates a sense of emergency where there is not one, and can draw unwanted attention to the chase crew. The chase crew is useless to the pilot if they have been stopped by the authorities.

While chasing, the crew should observe all “No Trespassing” and “Keep Out” signs, and stay on public, paved roads. Vehicular trespass is common and the laws are very restrictive regarding vehicles on private property. Pilots and their chase crews should adhere to local trespass laws.

If possible, the chase crew should try to keep the chase vehicle in sight of the balloon. The pilot needs to know the crew is nearby and not stuck in a ditch or off somewhere changing a flat tire. When the vehicle is stopped at the side of the road, park it so the entire vehicle is visible to the balloon pilot.

Pilot/Crew Communications

Radio communications between the balloon and the chase vehicle are fairly common. If radios are used, obey all Federal Communications Commission (FCC) regulations. Use call signs, proper language, and keep transmissions short. Many balloonists prefer not to use radios to communicate with their chase vehicle because it can be distracting to both pilot and chase vehicle driver. In any case, it is a good idea to agree on a common phone number before a flight in case the chase crew loses the balloon. [Figure 7-13]

Figure 7-13 This crew chief has stopped safely off the road to talk to her pilot. Communications are important, but safety is paramount.

Use of a Very High Frequency (VHF) Radio

There is confusion among pilots regarding frequencies that may be used from air-to-ground, balloon-to-chase crew, for instance. Many balloonists use 123.3 and 123.5 for air-to- ground (pilot-to-chase crew), as these frequencies are for glider schools and not many soaring planes are in the air at sunrise. Since all users of the airwaves must have an ID or call, ground crews may identify themselves by adding “chase” to the aircraft call sign. For example, the chase call for “Balloon 3584 Golf” would be “3584 Golf Chase,” or perhaps simply “84 Golf Chase.”

The air-to-air frequency is 122.75. Remember that everyone in the air is using this frequency; transmissions should be kept brief. A balloon pilot trying to contact a circling airplane would try 122.75 first.

Weather information is available on VHF radio. A balloon pilot could obtain nearby weather reports by tuning to the Automatic Terminal Information Service (ATIS). The appropriate frequency is listed on the cover of the sectional chart and in the airport information block printed on the chart near the appropriate airport.

Landowner Relations

Identification of Animal Populations

Balloonists must learn how to locate and identify animals on the ground. Even though it may be legal to fly at a certain low altitude, animals do not know the laws—nor do most of their owners. If a pilot causes dogs to bark, turkeys to panic, or horses to run, even while flying legally, it may provide legitimate cause for complaint.

Horses and ponies can be anywhere from the smallest paddock and roughest fields to the largest pasture. Boarding stables and breeding farms are easily identified by their painted wooden fences, stacked bales of hay and straw, and horse trailers. Assume all horses are valuable: race horses, breeders, and those privately boarded. While horses generally behave the same way when frightened, each one’s alarm level differs. Anything from the glow of the back-up burner to the balloon’s shadow can spook them. In a pasture, they may buck, neigh, or even charge; in extreme cases, they might try to jump the fence and may injure themselves. As horses are accustomed to hearing human voices, talking to them may help calm them down. [Figure 7-14]

Figure 7-14 Flight in areas of horse activity requires caution and consideration.

Cattle need more space than horses, about one acre per cow. Dairy cows tend to stay near the barn; corn near the pasture and a muddy yard usually means milk production. If they are out in more remote pastures, they are probably beef producers. When startled, cattle usually bunch together to face a threat but can just as easily panic and run. A stampede can break down a fence or locked gate. Once out, cattle can be herded by driving them from behind where they need to go by blocking sideways means of escape (with people or vehicles). Brood cows can be unpredictable, especially during breeding, and are capable of damaging a truck. As with horses, the sound of human voices may help calm cattle. [Figure 7-15]

Figure 7-15 While cattle in a field may appear undisturbed, they can spook and stampede at the least provocation.

Pigs are perhaps the most difficult livestock for farmers to raise. Easily disturbed, it is best to avoid them at all costs. When frightened, they bunch together and bolt, and are virtually unstoppable, almost impossible to catch, and potentially dangerous (especially boars). Pigs run until they are exhausted; rounding them up can take days. Pork prices fluctuate dramatically, and monetary claims against a balloonist who upsets pigs can be quite high.

Poultry (chickens and turkeys) are more often raised in confinement buildings than free range. A long windowless building with fans on the ends and atop the roof usually indicates a poultry production facility. With the lights and fans off, tens of thousands of birds can be amazingly quiet. Any disruption of this tightly controlled environment, however, can severely affect production. A sudden blast of a balloon’s burner can start an all-out panic; birds trying to flock in a confined space trample and crush each other, leading to mass-scale suffocation. Ducks and geese raised outside average about 200 birds per pen. When panicked, they also tend to flock which can lead to injury and death.

Livestock will appear along a balloon’s flightpath, as well as landing sites. Follow these livestock tips to minimize disruptions during these encounters:

- Always watch for signs of livestock: barns, sheds, silos, fences, muck heaps, tractors, trailers, stacked bales of straw and hay, and mudded areas all point to some form of livestock nearby.

- Stay away from barns and building clusters – livestock are most likely inside or nearby.

- Livestock are most active in the morning and early evening. When hot, they seek shade near buildings or under trees. When cold, they gather together to conserve heat and seek shelter from wind anywhere.

- Livestock breaking out of their field or enclosures as the balloon flies by demands immediate attention. A cow in the road can total a car; the driver will not do well either. The chase crew should either find the farmer or take steps to contain or protect the livestock without endangering themselves.The sound of a human voice can often calm agitated or frightened livestock—talk to them. Use calm and easy tones.

- Horses with riders warrant particular caution. A highly visible wave from the basket to the rider acknowledges their presence and says that all possible care is being taken.

Chapter Summary

As with the previous chapter, this chapter explains techniques and procedures that have come to be generally accepted throughout most of the ballooning community. They are by no means an exhaustive explanation of “how to fly.” Some of the procedures may seem unduly complex, but with practice and experience, these maneuvers come naturally.

A good pilot observes other pilots and incorporates techniques that are safe and acceptable. New pilots sometimes fly with different instructors, in order to gain a perspective on “how the other guy does it”; other, more experienced pilots fly with another commercial pilot during a flight review. Almost all flight methodology, as long as it is safely conducted, and with a plan and purpose behind it, is acceptable for use as long as the performance requirements of the PTS can be met.