Introduction

No other aircraft has as many different types of landings as a balloon. Rarely are two landings in a balloon the same, and each has its own unique characteristics. The prime consideration in any balloon landing is the safety of the pilot and passengers. While accessibility, ease of recovery, and possible damage to the balloon are certainly considerations in any balloon landing, these do not override the simple fact that preventing injury to occupants must be the primary goal of any balloon pilot.

Accident statistics indicate that the landing sequence is the portion of flight in which the most injuries occur.

The Approach

An axiom of ballooning is “the best altitude for landing is the lowest altitude.” Anyone can land from one foot above the ground; it takes skill to land from 100 feet. The pilot’s ultimate goal in making the approach is to set himself up to make a smooth, gentle landing in the best possible location without causing damage to the balloon or injury to the passengers.

Conventional wisdom indicates three types of approaches to landing in ballooning—stair step, straight line, and steep (previously discussed in Chapter 7, Inflight Maneuvers). In reality, the stair step and straight line approaches are considered the same type of approach, a controlled approach, while the steep approach is viewed as an accelerated approach. Any approach is considered to be a variation of one of these two or perhaps a combination.

Figure 8-1. Horizontal approach path as normally visualized and performed.

Of more importance, and a point frequently missed by newer or inexperienced pilots, is that the approach is being performed in two different planes or dimensions. Pilots are accustomed to thinking of the approach in vertical terms, but frequently discount the fact that the approach is also being performed on the horizontal plane.

Refer to Figure 8-1. This is the approach path to the selected landing site for this pilot. Most pilots presume that this will happen after making a determination of lower level winds, evaluating obstacle clearance, noting the presence of powerlines, and making the decision to commit to the landing. After that, the primary focus becomes making the descent without further consideration of the lateral or horizontal movement. In Figure 8-2, the pilot has determined the winds below, and has set up for the same approach ensuring obstacle clearance, powerline considerations, and making the commitment to land. The difference here is that the pilot has a higher level

Figure 8-2. The horizontal plane’s “reality” approach to landing

of situational awareness and understands the horizontal component, and therefore begins the approach with many more options available. In this example, if the pilot is tending more towards the road, he or she can “extend” the approach to remain in more favorable winds, and then continue the descent when the turn is more advantageous to the landing.

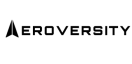

The vertical component of the landing profile is represented in Figure 8-3. This may be referred to as a “natural” descent profile. For example, the pilot may see a large field in the distance ahead and elect to initiate a shallow or low profile approach. The pilot would let the balloon cool naturally until it reached the point depicted as Point A in Figure 8-3. A normal descent rate at that point would project the balloon out on a line tangent with the descent curve at that moment. From that point, the pilot must maintain that line much like the control necessary for contour flying.

If, however, the winds are somewhat lighter or the landing site is tight, conducting the approach from Point B, Figure 8-3 might be more appropriate. Again, the pilot should wait until the tangent of the descent curve aligns with the targeted

Figure 8-3. Vertical profile for landing.

landing site. At that point, the pilot should make a half burn and the balloon will follow the desired path.

As a final illustration, steep descents, as previously discussed in Chapter 7, are usually initiated and controlled from the point or area depicted as C in Figure 8-3. The pilot must take both planes of movement, the horizontal as well as the vertical, into consideration when making the approach.

Again, the balloon pilot must visualize the landing by imagining the path through the air and across the ground. Constant scanning in all directions while on the desired approach is imperative. Target fixation can cause a pilot to miss potentially dangerous objects or situations. Look for obstacles, especially powerlines, near the imagined track. Note surface wind velocity and direction by looking for smoke, dust, flags, moving trees, and anything else that indicates wind direction. Do not be influenced too much by a wind indicator at a distance from the proposed site if there is a good indicator closer.

As an example, imagine flying level at 700 feet above ground level (AGL) and it is time to land. Checking the fuel, there is 30 percent remaining in each of the two 20-gallon tanks. The balloon’s track across the ground is toward the southeast, but a farmer’s tractor is observed making a column of dust that is traveling nearly due east. The dust cloud rises from the ground at about a 45° angle. From this information, it is believed that the balloon turns left as it descends. This means the pilot is looking to the left of the line the balloon now travels. By dropping small tissue balls, the pilot determines that the wind changes about halfway to the ground and continues to turn left about 45°. As an initial plan, visualize the descent being no faster than about 500 feet per minute (fpm) initially and slowing to about 300 fpm about 400 feet AGL where the turn to the left can be expected. Because the balloon loses some lift from the cooling effect of the wind direction change, the rate of descent should be closely monitored during the turn.

With this imagined descent in mind, the pilot searches for an appropriate landing site. The next fallow field to the left of the present track is blocked by tall powerlines. The landing site is rejected as unsuitable. The next field that seems appropriate is an unfenced grain stubble field bordered by dirt roads with a 30-foot high power line turning along the west side to the left and parallel to the balloon’s present track. Under the powerlines is a paved road with a row crop of sugar beets to the right and directly in the balloon’s ground track.

The pilot selects a landing site at the intersection of the two dirt roads at the southeast corner of the field. The planned path would be across the field diagonally giving the greatest distance from the powerlines. Extending the final approach line back over the powerlines and into the sugar beet field, the pilot selects a point where the balloon is likely to begin its surface wind turn. Then, reverse planning from that point, a point should be determined in order to begin the initial descent.

Now, the balloon pilot performs the descent, turn, and landing that is visualized. If all goes as planned, the balloon cools and accelerates to about 500 fpm. The pilot applies some heat to arrest the descent while approaching the imagined turning point over the beets, levels off (or actually climbs a bit) while crossing over the power lines (about 100 feet above), and allows the balloon to cool again while setting up another descent across the stubble field. Due to the seven mile per hour (mph) estimated wind, the pilot allows the basket to touch down about 150 feet away from the dirt road intersection to lose some momentum as the basket bounces and skids over to the road, just as planned.

Imagine, how the landing might have occurred not knowing the surface wind was different from that of the flight path. Perhaps a less considerate pilot would plan on landing in the beets, believing the crop would not be hurt and the farmer would not care. Unfortunately, the balloon turns unexpectedly toward the power lines, causing the pilot to make several burns of undetermined amount, setting up a climb that prevents the pilot from landing on the dirt road. The road is directly in line with the balloon’s track but disappearing behind the balloon. Another good landing site becomes unusable because of the lack of planning.

The prudent pilot makes a nice landing on a dirt road with 25 percent fuel remaining, while the unprepared pilot dives, turns, climbs, and is now back at 600 feet in the air looking for another landing site. For the next attempt, the pilot has less fuel and is under more pressure, all because of not noticing the power lines to the left and not checking the wind on the ground before making the descent.

Step-Down Approach

The step-down approach method involves varying descent rates. This procedure is used to determine lower level wind velocities and directions so that options may be considered until beginning the final descent phase to landing. There are other methods to evaluate lower level wind conditions, such as dropping strips of paper, small balloons, etc. While the descent path can be varied and sometimes quite shallow,

Figure 8-4. The step-down approach.

it is important to avoid long, level flight segments below minimum safe altitudes without intending to land. Level flight at low altitudes could lead an observer to believe that the pilot has discontinued the approach and established level flight at less than a minimum safe altitude. [Figure 8-4]

Low Approach

The second type of approach is a low or shallow approach. If there are no obstacles between the balloon and the proposed landing site, a low or shallow approach allows a pilot to check the wind closer to the surface. The closer the balloon is to the surface, the easier it is to land. Low approaches are suitable in open areas with a wide field of view and few obstacles.

Obstacles and Approach Angles

Most good landing areas are not very large and generally have obstacles somewhere close by. The classic approach requires the balloon pilot to fly the balloon at a descent angle that clears the highest obstacle in its path to the intended landing site. However, if the pilot allows the balloon to descend below that angle, a rapid adjustment of that angle is necessary to avoid the top of the obstacle. In many cases, the attempt to miss an obstacle by a close margin may result in a period of overcontrolling or excessive burns and vents.

Figure 8-5. In this approach, the pilot has elected to clear the obstacle at a minimal distance. Any overcontrol after Point A is likely to send the balloon past the intended landing area, and a very close clearance will be necessary over the obstacle at Point B in order to preserve the desired approach angle.

The inexperienced pilot usually misses the intended landing site and is forced to find another or has an undesirably hard landing, if the pilot manages to make the landing site. See Figure 8-5 for an illustration of this effect. This type of approach is helpful by keeping the intended landing area in focus so that the descent results in the balloon touching down precisely where intended. Benefits to this methodology are straight line control and immediate visual feedback from the landing site. The disadvantage of using this specific methodology is that, again, any deviation from the depicted flight path may result in overcontrol or, at best, a “close shave” over the obstacle at Point B to preserve the approach.

Figure 8-6. This approach is virtually the same as the one in Figure 8-5, but with subtle differences. In this case, the pilot has aimed for a location above the obstacle at Point B with appropriate obstacle clearance. Minor deviations after Point A on the approach path, if compensated for, still allow the pilot to make the intended landing area.

Figure 8-6 illustrates the same vertical profile but with a few subtle and important differences. The initial approach is identical, but the initial target is different. Rather than focusing on the landing site past the barn requiring a clearance of two or three feet, this pilot has elected to “aim” for a point of safe obstacle clearance of the barn (about ten feet above the silo), knowing that a short vent on the other side “sharpens” the descent. It is clear that the balloon drops into the landing site somewhat closer to the obstacle, the conscientious pilot having already evaluated that possibility prior to committing to the landing. This methodology minimizes the possibility of overcontrolling and dramatically increases the chances of a successful landing .

To summarize, if there is an obstacle between the balloon and the landing site, the following are the three safe choices.

- Give the obstacle appropriate clearance and drop in from altitude.

- Reject the landing and look for another landing site.

- Fly a low approach to the obstacle, fly over the obstacle allowing plenty of room, and then make the landing.

The first choice is the most difficult, requiring landing from a high approach and then a fast descent at low altitude. The second choice is the most conservative, but may not be available if the pilot is approaching the last landing site. The third choice is preferable. Flying toward the site at low altitude provides an opportunity to check the surface winds. By clearing the obstacle while ascending—always the safest option—the pilot ends up with a short, but not too high, approach.

Some Basic Rules of Landing

When a landing site is being considered, a balloon pilot should first think about the suitability of the site. “Is it safe, is it legal, and is it polite?”

Plan the landing early enough so that fuel quantity is not a distraction. Always plan on landing with enough fuel so that even if the first approach to a landing site is unsuccessful, there is enough fuel to make a couple more approaches.

The best landing site is one that is bigger than the balloon needs and has alternatives. If the balloon has three prospective sites in front of it, the pilot should aim for the one in the middle in case the surface wind estimate was off. If the balloon has multiple prospective landing sites in a row along its path, the pilot should take the first one and save the others for a miscalculation. Unless there is a 180° turn available, all the landing sites behind are lost. Before beginning the approach, the pilot should plan to fly a reasonable descent path to the landing site using the step-down approach, the low (shallow) approach, or a combination of the two.

Congested Areas

Making an approach in a congested area, and subsequently discovering the site to be impossible or inappropriate, is another example of a situation in which a pilot could be falsely accused of low flying. There are some inconsiderate pilots who fly too low in congested areas without reason, but they are rare. Every pilot has an occassional aborted landing situation. According to Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations (14 CFR) part 91, section 91.119, a balloon may fly closer to the ground than the minimum altitude, if necessary for landing. For example, during the approach the balloon turns away from the obviously preferred landing site, but there is another possible site only one-half mile in the proper direction. The pilot has two choices: (1) go back up to a legal altitude and try again, or (2) stay low in the wind that the balloon pilot is sure will carry the balloon to a good site and try to make the second landing site.

In making the first choice, the pilot could be accused of intentionally flying too low. However, with the second choice, he or she flies lower for a longer period of time, which might appear to be a blatant violation of the minimum altitude regulation. This is not an argument in favor of either technique. Many pilots prefer the second choice on the “once the pilot goes down to land, he or she had better land” theory. [Figure 8-7]

Figure 8-7. A good landing is something to watch.

Practice Approaches

Approaching from a relatively high altitude with a high descent rate down to a soft landing is a very good maneuver to practice periodically, regardless of the experience level of the pilot. This is used when landing over an obstacle and maneuvering to the selected field is possible only from a higher than desired altitude. This maneuver can also be used when, due to inattention or distractions, the pilot is at a relatively high altitude approaching the last appropriate landing site. Practicing this type of approach should take place in an uninhabited area and the obstacle should be a simulated obstacle.

A drop-in landing or steep approach to landing is another good maneuver to practice. Being able to perform this maneuver can get the balloon into that perfect field that is just beyond the trees or just the other side of the orchard. A pilot that is able to drop quickly, but softly, into the fallow field between crops is more neighborly than making a low approach over the orchard. Being able to avoid frightening cattle or other animals during an approach is a valuable skill.

Having the skill to predict the balloon’s track during the landing approach, touching down on the intended landing target, and stopping the balloon basket in the preferred place can be very satisfying. It requires a sharp eye trained to spot the indicators of wind direction on the ground. Dropping bits of tissue, observing other balloons, smoke, steam, dust, and tree movement are all ways to predict the balloon track on its way to the landing site. During the approach, one of the pilot’s most important observations is watching for power lines. In ballooning, approaches can be practiced more often than landings. A good approach usually earns a good landing

Figure 8-8. Anatomy of a thermal. A thermal is created by the uneven heating of the surface of the Earth by solar radiation (insolation). As the sun heats the ground, the ground in turn warms the air above it. Warmer air is less dense, and therefore rises; as it rises, it cools due to expansion. This heating/cooling pattern sets up a cycle, whereby a downward flow is created outside the thermal column one the air has cooled to a temperature equal to that of the surrounding air. This can create a hazardous situation for a balloon pilot; the best action is to maintain buoyancy, and wait for the column to dissipate.

Thermal Flight

The experience of being caught in a thermal can certainly occur at any altitude, but is more common during the landing phase of balloon flight. This is primarily due to the balloon’s proximity to the ground and being exposed to the conditions that cause thermals. [Figure 8-8]

There are indicators of thermal conditions that may be visible to the pilot, such as “dust devils” or small tornados visible from the ground. An uncommanded ascent, usually at a significant climb rate, may be experienced, or perhaps significant changes in direction. In the extreme, a balloon caught in a tight (compact) thermal may even create small horizontal circles in the sky.

There are two rules to thermal flight. First, the pilot must continue to fly the balloon. Many pilots are distracted by the thermal flight experience and may forget that the balloon is cooling at a faster than normal rate. The pilot should ensure that the temperature of the balloon’s envelope is kept at or above that required to maintain normal flight, and under no circumstance should the pilot allow the balloon to cool. The temperature noted at equilibrum should be a minimum temperature to maintain. Additionally, the pilot should not vent in an effort to descend and land; if the balloon falls out of the thermal, the pilot may not have sufficient altitude to recover control.

The second rule of thermal flight is the axiom, “altitude is your friend.” Thermals are usually short-lived phenomena and dissipate after a brief period of time. If the pilot keeps the balloon at flight temperature, the thermal usually “spits” the balloon out at a higher altitude. When this happens, the balloon can again be controlled by the pilot and a safe landing may be executed.

Landings

Landing Considerations

When selecting a landing site, three considerations in order of importance are: safety of passengers, as well as persons and property on the ground; landowner relations; and ease of recovery.

Some questions the pilot should ask when evaluating a landing site are:

- Is it a safe place for my passengers and the balloon?

- Would my landing create a hazard for any person or property on the ground?

- Will my presence create any problems (noise, startling animals, etc.) for the landowner?

High-Wind Landing

When a high-wind landing is likely, the pilot should explain to the passengers that a high-wind landing follows. It is better to alert them than allow them to be too casual. Passengers should be briefed again on the correct posture and procedures for a high-wind landing, to include wearing gloves and helmets, if available or required. Some pilots with dual burner systems elect to leave one burner operational through the landing process, in the event that heat must be applied to climb out of a bad approach. This decision should be made with a view towards the intensity of the impact; a pilot must also be aware that, instinctively, he or she may grab the burner handle during a rough landing. This could result in burner activation, damaging the balloon fabric.

The pilot should fly at the lowest safe altitude to a large field and check that the deflation line is clear and ready. Obstacles should be avoided and the pilot should ideally make an approach to the near end of the field. When committed to the landing, brief passengers again, turn off fuel valves, drain fuel lines, and turn off pilot lights.

Depending on the landing speed and surface, open the deflation vent at the appropriate time to control ground travel. The passengers should be closely monitored to ensure they are properly positioned in the basket and holding on tightly.

Deflate the envelope and monitor it until all the air is exhausted. Be alert for fire, check the passengers, and prepare for recovery.

When faced with a high wind landing, the balloon pilot must remember that the distance covered during the balloon’s reaction time is markedly increased. This situation is somewhat analogous to the driver’s training maxim of “do not overdrive your headlights.” For example, a balloon traveling at 5 mph covers a distance of approximately 73 feet in the 10 seconds it takes for the balloon to respond to a burner input—a distance equal to a semi-truck and trailer on the road. However, at a speed of 15 mph, the balloon covers a distance of 220 feet, or a little more than two-thirds of a football field. A pilot who is not situationally aware and fails to recognize hazards and obstacles at an increased distance may be placed in a dangerous situation with rapidly dwindling options.

Water Landings

Landing in water requires modification to the passenger briefing. In a ditching, make sure the passengers get clear of the basket in case it inverts due to fuel tank placement. Advise the passengers to keep a strong grip on the basket because it becomes a flotation device. Predicting the final disposition of the basket in water is difficult. If the envelope is deflated, the pilot and passengers can expect the envelope to sink, as it is heavier than water. Fuel tanks float because they are lighter than water, even when full. If the envelope retains air, and depending on fuel-tank configuration, the balloon basket may come to rest, at least for a while, on its side.

If the water landing is done on a river, the balloon may be dragged down river in the current. Generally, staying with the basket is the best course of action unless the balloon has landed close to the bank and those aboard are strong swimmers.

Passenger Briefings and Management

Prior to landing, the pilot should explain correct posture and procedure to the passengers. Many balloon landings are gentle, stand-up landings. However, the pilot should always prepare passengers for the possibility of a firm impact. The prelanding briefing should instruct passengers to do the following:

- Stand in the appropriate area of the basket.

- Face the direction of travel.

- Place feet and knees together, with knees bent.

- “Hold on tight” in two places.

- Stay in the basket.

Stand in the Appropriate Area of the Basket Passengers and the pilot normally position themselves toward the rear of the basket. [Figure 8-9] This accomplishes three things.

- The leading edge of the basket is lifted as the floor tilts from the occupant weight shift, so the basket is less likely to dig into the ground and tip over prematurely.

- With the occupants in the rear of the basket and the floor tilted, the basket is more likely to slide along the ground and lose some speed before tipping.

Figure 8-9. Landing with passengers

- The passengers are less likely to fall out of the front of the basket.

In a high-wind landing, passengers should stand in the front of the basket because if the basket makes surface contact and tips over, passengers fall a shorter distance within the basket and are not pitched forward. They are more likely to remain in the basket, minimizing the risk of injury.

Face the Direction of Travel

Feet, hips, and shoulders should be perpendicular to the direction of flight. Impact with the ground while facing the side puts a sideways strain on the knees and hips, which do not naturally bend that way. Facing the opposite direction is more appropriate under certain conditions. Recall the discussion on passenger briefings on page 6-12.

Place Feet and Knees Together, with Knees Bent To some people this may not seem to be a natural ready position; however, it is very appropriate in ballooning. The feet and knees together stance allows maximum flexibility. With the knees bent, one can use the legs as springs or shock absorbers in all four directions. With the feet apart, sideways flexibility is limited and knees do not bend to the side. With legs apart fore and aft, one foot in front of the other, there is the possibility of “doing the splits” and a likelihood of locking the front knee. Avoid using the word brace as in “brace yourselves,” as that gives the impression that knees should be locked or muscles tensed. Legs should be flexible and springy at landing impact.

“Hold On Tight” in Two Places

This is probably the least followed of the landing instructions. Up to this point, the typical balloon flight has been relatively gentle, and most passengers are not mentally prepared for the shock that can occur when a 7,000 pound balloon contacts the ground. Passengers should be reminded to hold on tight. The pilot should advise the passengers of correct places to hold, whether they are factory-built passenger handles or places in the balloon’s basket the pilot considers appropriate. The pilot should obey his or her own directions and also hold on firmly.

Stay in the Basket

Some passengers, believing the flight is over as soon as the basket makes contact with the ground, start to get out. Even a small amount of wind may cause the basket to bounce and slide after initial touchdown. If a 200-pound passenger decides to exit the basket at this point, the balloon immediately begins to ascend. All passengers should stay in the basket until individually told by the pilot to exit.

Monitoring of passengers is important because, after the balloon first touches down, passengers may forget everything they have been told. A typical response is for the passenger to place one foot in front of the other and lock the knee. This is a very bad position as the locked knee is unstable and subject to damage. Pilots should observe their passengers and order “feet together,” “front (back) of the basket,” “knees bent,” “hold on tight,” and “do not get out until I tell you.” The pilot should be a good example to passengers by assuming the correct landing position. Otherwise, passengers may think, “If the pilot does not do it, why should we.”

It is very important that the passenger briefing be reinforced more than once. Some balloon ride companies send an agreement to their passengers in advance which includes the landing instructions. Passengers are asked to sign a statement that they have reviewed, read, and understand the landing procedure. Many pilots give passengers a briefing and landing stance demonstration on the ground before the flight. This briefing should be given again as soon as the pilot has decided to land.

The pilot is very busy during the landing—watching the passenger’s actions and reactions, closing fuel valves, draining fuel lines, cooling the burners, and deflating the envelope. The better the passengers understand the importance of the landing procedure, the better the pilot performs these duties and makes a safe landing.

Recovery

Landowner Relations

The greatest threat to the continued growth of ballooning is poor landowner relations. The emphasis should be to create and maintain good relations with those who own and work the land that balloonists fly over and land on. Balloon pilots must never forget that, at most landing sites, they are unexpected visitors. Balloonist may think the uninvited visit of a balloon is a great gift to individuals on the ground. The balloon pilot may not know the difference between a valuable farm crop and uncultivated land. A balloonist may not notice grazing cattle. A chase vehicle driver may drive fast down a dirt road, raising unnecessary dust. A crewmember may trample a valuable crop.

There are several situations where a balloon pilot or crew may anger the public. When people are angered, they demand action from the local police, county sheriff, Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), or an attorney. The FAA does not initiate an investigation without a complaint. The balloonist is the one who initiates a landowner relations problem.

A balloonist can ease the effect he or she has on people on the ground. First, the pilot should develop skills to allow the widest possible selection of landing sites. The pilot should ensure that the crew is trained to respect the land, obey traffic laws, and be polite to everyone they come in contact with. The crew should always get permission for the balloon to land and the chase vehicle to enter private property.

Each pilot should learn the trespass laws of his or her home area. In some states, it is very difficult for the balloon pilot and passengers to trespass, but very easy for the chase vehicle and crew to trespass. If the balloon lands on the wrong side of a locked gate or fence, the first thing the chase crew should do is try to find the landowner or resident to get permission to enter. If no one can be found, it may be necessary to carry the balloon and lift it over the fence.

Do not cut or knock down fences, as it is probably considered trespassing. In some places, even the possession of fence- cutting and fence-repairing tools may be interpreted as possession of burglary tools, creating liabilities. Pilot and crew should have a clear understanding of what is acceptable and what is not acceptable.

Sometimes local law enforcement officials arrive at the scene of a balloon landing site. Someone may have called them or they may have seen the balloon in the air. They may just be interested in watching the balloon (which is usually the case), or they may think a violation of the law has occurred. If law enforcement officials approach the balloon, the pilot should always be polite. Most emergency responders probably do not know much about federal law regarding aviation. However, even if they are wrong and the pilot knows they are wrong, there is no point in antagonizing them with a belligerent attitude. It is better to listen than to end up in court.

There is a wealth of information on landowner relations issues available from the Balloon Federation of America (BFA), as well as the British Balloon and Airship Club (BBAC). The BBAC web site, www.bbac.org, has an excellent video that was produced solely to deal with the issues of landowner relations in the United Kingdom. Despite being tailored for that country, it is worth viewing by the pilot and crew in the United States.

Packing the Balloon

After the crew has obtained the necessary landowner clearance to enter the landing site, the process of packing the balloon begins. Despite being the end of the flight, many pilots, as well as crew, consider this the point when the real work begins.

Deflating the balloon is the reverse of the inflation process. The crewmember designated to handle the crown line should secure the free end of the crown line and move downwind. The pilot should turn off the burner’s pilot light and main fuel valves on the fuel tanks, and vent the fuel system. Once the fuel system has been shut off, and there is no risk of fire, the vent line can be activated to start the deflation. The crown line crewperson pulls on the crown line to assist in the deflation process and to help lay the balloon out in the desired direction. The pilot and crew should remember that it is virtually impossible to lay a balloon down against the wind. Other crewmembers may be stationed on the sides to keep fabric from draping over trees, bushes, and assist the balloon in coming down. Once the envelope is on its side, the crown line crewmember may move to the top of the balloon, and maintain slight tension on the load ring in order to continue the deflation. This crewmember should be reminded to leave gloves on, as the load ring is hot and may take some time to cool.

At this point, the balloon is ready to be “walked out,” or “squeezed,” meaning that the remaining air in the balloon is removed in preparation for repacking the envelope in the appropriate bag. The most common method is for the pilot or a crewmember to gather the envelope together at the throat, and, keeping their arms around the fabric, walk towards the top of the envelope squeezing the air out as they go. There is ample opportunity during this process to injure one’s back. The person walking the envelope out should take care to not put excessive strain on their lower back during this process. There are some mechanical devices available to help in this process, and some pilots elect to use one of these, rather than put an individual’s well being at risk. [Figure 8-10]

Figure 8-10. Walking the balloon out with a “Squeeze-EZ.”

After the envelope is walked out and the crown line is secured, either in a separate bag or by folding it in half down the length of the envelope (which prevents tangling), the envelope is ready to be packed in its bag. The envelope bag, regardless of manufacturer, has a “flap” of fabric across the top. Some pilots prefer to pack the envelope so the flap is towards the balloon, while others prefer that the flap be away from the balloon. At first glance, this appears to be a random choice but there is sound reasoning behind it. If the balloon is usually launched from grassy, smooth fields, then it would be normal to have the flap away from the balloon. If, however, the balloon is laid out for inflation in areas with rocks, stubble, and other objects which may potentially damage the envelope, it is an accepted practice to pack the balloon with the envelope flap facing towards the balloon. Then, when the balloon is laid out on the next flight, it passes over the flap before contact with the ground and minimizes the risk of damage. [Figure 8-11]

Figure 8-11. Packing the balloon. This pilot has elected to position the envelope bag near the basket and is bringing the balloon to the bag, rather than picking up the bag each time to move it towards the basket. Some pilots prefer this method, as it means less lifting for the crew.

Crewmembers should be stationed on opposite sides of the bag at a 90° angle to the balloon. The pilot or designated crewmember lifts a section of the balloon and, with the crewmembers lifting the bag and bringing it to the envelope, place it in the envelope bag. This process continues until the envelope is almost completely packed and only the suspension cables are out. The suspension system is removed from the basket superstructure and secured, and placed in the envelope bag. The bag is closed and loaded on the chase vehicle.

Actions at this point are performed in the reverse order of the layout procedure. Generally, the envelope is secured onto the chase vehicle, the basket and burners are disassembled and secured on the vehicle, and a final check of the landing site is made to ensure that no loose items are left at the landing site. A final check with the landowner is usually appropriate. After a quick “thank you,” the flight is officially “one for the books.”

Refueling

Most pilots choose to refuel as soon after a flight as possible. This is probably appropriate for most circumstances, as this is one less issue to resolve when the time comes for the next flight. [Figure 8-12]

Figure 8-12. Refueling. Note that this pilot is exercising safety precautions with sleeves down and gloves on.

Each balloon has its own refueling procedures, which may be found in the appropriate flight manual for that balloon. Refueling involves connecting a supply line to the balloon’s fuel lines, opening the refueling tank’s main valve, opening a fixed liquid level gauge (“spit” valve) on the respective fuel tank in the balloon basket, and then opening the main supply valve on that tank. When the fixed liquid level gauge begins to “spit” liquid propane, the tank is full. Shut off the main tank valve first, then close the “spit valve,” then close the main supply line, and then bleed the lines. This is a generalized description of the process; under all circumstances, the pilot should follow the procedure as outlined in the balloon’s flight manual.

Safety during refueling is of paramount importance. While specific refueling procedures may vary, safety procedures do not. Propane vapor is a highly flammable and, under certain circumstances, explosive gas. There are many instances of accidents during refueling that have resulted in property damage, personal injury, and even death. The following safety rules serve the balloon pilot well to remember:

- No smoking around the balloon while refueling. This is an absolute.

- Never conduct refueling procedures from inside the basket.

- Disable strikers in the basket. Turn off cell phones and pagers. Synthetic clothing may also provide a source of ignition (static electricity) under certain circumstances.

- The chase vehicle should be shut off. Do not leave the engine running during the refuel process. In larger chase vehicles, such as RV conversions, water heater pilot lights must be shut off.

- Persons conducting the refueling should wear gloves at all times, preferably loose ones that can be removed quickly.

- Never refuel inside a closed trailer or inside a van. The vapor can quickly build up to a potentially combustible level. The basket should be moved to open air, as propane vapor is heavier than air.

For further safety recommendations, a pilot should consult with the propane supplier or see the appropriate section of the Hot Air Balloon Crewing Essentials publication previously cited in this handbook.

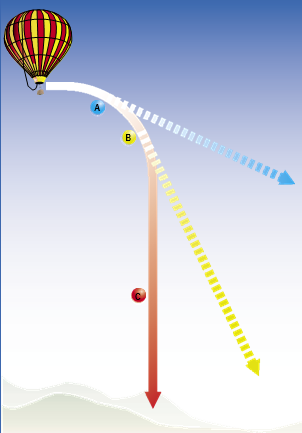

Logging of Flight Time

At some time subsequent to the flight, it is necessary for the pilot to make entries regarding the flight in their personal logbook, as well as the aircraft’s logbook. It is an accepted practice in aviation that flight time is logged in tenths of a hour, as opposed to using hours and minutes. A tenth of an hour is represented by a 6-minute increment; remaining minutes are rounded up. This practice is used for both individuals and aircraft.

Pilot’s Log

A pilot’s flight time is required to be logged under the provisions of 14 CFR section 61.51. That section states, in part, that …“(1) Each person must document and record the following time…(a) training and aeronautical experience used to meet the requirements for a certificate, rating, or flight review of this part. (2) The aeronautical experience required for meeting the recent flight experience requirements of this part.” (in this case, referring to currency requirements as stipulated under section 61.57) This is a relatively simple requirement and usually does not present issues for the pilot.

There are certain definitions relating to solo time, pilot in command (PIC) time, and instruction time, which are explained within the regulation. Pilots are advised that since they alone are responsible for maintaining the log books, knowledge of these definitions is necessary. Reviewing section 61.51 is appropriate. Should questions arise, a pilot should consult with the local Flight Standards District Office (FSDO) for interpretation.

Aircraft Log Books

14 CFR section 91.417 addresses the requirement for aircraft maintenance records (commonly referred to as a log book), and what the record must contain. All time recorded on the aircraft must be reflected in the maintenance record, and it is the responsibility of the owner or operator of the aircraft to ensure that the records are correctly maintained.

Flight time in a balloon is defined as that time beginning when the balloon is first made buoyant and lasts until the balloon is deflated. Balloons do not have a hour meter, as an airplane or other aircraft does, and the pilot must consider the fact that burner activation on inflation would equate to an engine start on an airplane. [Figure 8-13]

Figure 8-13. Aircraft log books or maintenance records are for aircraft time and not for passenger names and flight experiences.

There are some pilots who do not, for whatever reason, record aircraft time conducted while on tether. This is an incorrect practice. A balloon on tether is in flight, or more precisely, in a flight configuration, and conducting operations under the provisions of part 91. All inflated time of a certificated balloon should be noted in the maintenance records to ensure that inspection times are met.

Crew Responsibilities

The general theory regarding expectations of crew help at landing is if the pilot cannot land the balloon without help, he or she should not be flying. It is not always possible for the chase crew to be at the landing site, so plan to land without assistance.

Most balloon pilots have strong opinions regarding whether or not the crew must be present for a landing. Those who do not see a need for crew to be present have some solid reasons.

- It is not always possible for crew to be there. Traffic, wrong turns, and pilot decisions to land early or fly on can thwart their best efforts.

- With no formal training, enthusiastic crew might interfere with the landing or do the wrong thing and create a problem where none would have existed.

- Crew racing to every potential landing site may drive inconsiderately and even recklessly, endangering everyone on the road and creating a poor impression for ballooning.

Pilots who favor crew being on hand have a number of equally convincing arguments.

- In any branch of aviation, takeoff and landing are the most critical maneuvers. In ballooning, landing is number one. The vast majority of ballooning accidents and injuries occur on landing. A mistake during inflation or launch usually means calling a repair station; burned throat fabric is the leading repair nationwide. A mistake during landing often means calling the insurance agent. One insurance survey found accidents involving bodily injury on hard landings occur twice as often as damage to equipment or even power line strikes. This trend clearly identifies a need to improve safety at the end of every flight.

- The leading factor in accidents is wind. Highly variable surface winds often speed up, slow down, stop, turn, and even go backward. Crew onsite can radio the pilot regarding surface wind speeds and directions prior to landing, which factor into landing at a particular site, if at all.

- Landing approaches put the balloon at its closest to power lines, trees, buildings, and the ground. Potential risks increase, and the closest first responders able to handle the balloon and trouble are most likely to be the crew.

- When flying low or into the sun, a pilot may not see hidden power lines, antennas, or other obstacles which crew can easily spot while assessing the landing site.

- Crew can confirm the quality of a landing site. From a distance, a pilot cannot see what may rule the site out: livestock gathered under a tree, standing water, a newly planted crop, another balloon deflating in the field, etc. The crew may find a site the pilot might not have seen from the air.

- Many pilots ask crew to get landowner permission before committing to a site or actually landing. This is often a crew’s top priority. Finding the landowner can take a few minutes; one crewmember can do this while another walks out to assist the pilot. If it is a “no,” time and fuel might have been better spent searching for the next suitable option.

- Landings create a workload challenge for the pilot. Consider all the tasks in the seconds before and after landing: flying the balloon, making an approach, briefing passengers, watching for obstacles, bracing for landing, deciding to move closer to a road or driveway, shutting down tanks, bleeding fuel lines, radioing crew, directing passenger unloading, deflating the envelope, keeping the envelope off obstacles, dealing with a hostile landowner or dog, and more. A single oversight, distraction, or poor decision can compromise safety. Extra hands may be required to protect everyone onboard and on the ground

- Crew serve as a pilot’s redundancy and work to minimize flight risks of any nature. The FAA and every balloon manufacturer know the safety value of redundancy and the greatest risks (accidents and injuries) come at landing. There is no better time for crew to promote safety than in the flight’s last minutes.

While crew-assisted landings may make some pilots uncomfortable, the reality is they happen all the time. This crew role can perhaps have more impact on flight safety than any regulation, equipment, or technique, provided the pilot and crew decide this before the flight. Sometimes the best landing assistance may be none at all. Every pilot is trained to land without help from their crew. The balloon pilot may have chosen a landing site—fully visible from the air, with no obstacles, and perfect as is—early in the flight. Conditions are often smooth enough for safe landings. An unassisted landing often gives the pilot a better feel for the balloon’s equilibrium. Letting the ground absorb the balloon’s energy by touching and/or dragging might be the safest option of all. The landowner might greet the pilot in person even before the crew arrives, and passengers may have equipment disassembled and packed before the crew arrives. Many of these conditions frequently occur. A thoroughly prepared crew is one that is trained and ready for the many occasions that they are needed.

Chapter Summary

Among the many adages in aviation is “takeoffs are optional, landings are mandatory.” For every flight, there must be a landing, and the balloon pilot should be prepared to execute a landing with skill and precision at any time during the flight.

In the early days of ballooning, it was common to see pilots “stick” the balloon (execute a hard landing) on a routine basis as burner systems were generally inadequate to slow the balloon during a rapid descent. With newer systems, the balloon can be better controlled and a smooth, graceful landing is a routine result, provided the pilot has planned ahead and understands the mechanics and concepts of the landing process. The information contained here is by no means all inclusive, but illustrates certain methodologies to good landing techniques.