As previously discussed in Chapter 1, commercially rated balloon pilots have the additional responsibility and privilege of providing instruction to aspiring student pilots, without the benefit of having a certified flight instructor (CFI) rating. This is unique to balloon pilots, as all other aircraft pilots require instruction by a CFI in order to achieve their certificate.

Flight training, whether in an airplane, helicopter, or a balloon, should be conducted in a complete and thorough manner in order to prepare the student pilot to safely conduct flight operations throughout the entire spectrum of scenarios. An ill-prepared instructor can produce only an ill-prepared student. A well-prepared instructor produces a well-prepared student, and he or she reaps the additional benefit of showing the student how instruction should be conducted. That pilot, in later stages, reflects on his or her own training and probably conducts future training in the same manner. The flight instructor is the central figure in aviation training and is responsible for all phases of required training. The instructor must be fully qualified as an aviation professional; however, the instructor’s ability must go far beyond this if the requirements of professionalism are to be met. Although the word “professionalism” is widely used, it is rarely defined. In fact, no single definition can encompass all of the qualifications and considerations that must be present before true professionalism can exist.

When discussing professionalism, most conversations omit any reference to the accountability of the instructor. An individual who takes on the responsibility of providing flight instruction must realize that they have a significant influence on the habits and actions of the student as a pilot. All of the student’s impressions and perceptions towards the flight experience, balloon operations, and, most importantly, safety is drawn from the instructor’s methods. It becomes imperative that the instructor understand that he or she, by default, actively and passively contributes to the future actions of the student and should make every effort to provide the most thorough training experience possible. It can be said that many students become “clones” of their instructor.

Though not all inclusive, the following list gives some major considerations and qualifications that should be included in the definition of professionalism.

- Professionalism exists only when a service is performed for someone or for the common good.

- Professionalism is achieved only after extended training and preparation.

- True performance as a professional is based on study and research.

- Professionalism requires the ability to make good judgment decisions. Professionals cannot limit their actions and decisions to standard patterns and practices.

- Professionalism demands a code of ethics. Professionals must be true to themselves and to those they serve. Anything less than a sincere performance is quickly detected by the student and immediately destroys instructor effectiveness.

- Professionalism requires that the individual instructor be able to conduct a self-assessment. A true professional must be able to critique his or her own performance with objectivity.

Flight instructors should carefully consider this list. Failing to meet these qualities may result in poor performance by both instructor and student. Preparation and performance as an instructor with these qualities in mind commands recognition as a professional in aviation instruction. Professionalism includes an instructor’s public image.

A more complete discussion of the information contained in this chapter may be found in FAA-H-8083-9, Aviation Instructor’s Handbook. There have been some minor changes in this chapter to address the specific aspects of balloon flight training. For expanded discussions of the areas of operation covered in the Commercial Pilot Practical Test Standards (PTS), (FAA-S-8081-18), the Aviation Instructor’s Handbook is required reading. Commercial pilots who wish to excel at the instruction process may consider taking the Fundamentals of Instruction knowledge test administered through the FAA’s knowledge testing program. While not a mandatory requirement, it is believed that the study necessary to successfully complete this exam assists the pilot/instructor in acquiring the knowledge necessary to plan and perform proper aviation training.

For the remainder of this chapter, it should be understood that the term “flight instructor” is meant to define those individuals who hold a commercial pilot certificate with a free balloon category rating. This chapter also makes the presupposition that virtually all balloon flight training is performed “one on one,” and not as part of a group environment.

Flight Instructor Characteristics and Responsibilities

Students look to flight instructors as authorities in their respective areas. It is important that flight instructors not only know how to teach, but they also need to project a knowledgeable and professional image. In addition, flight instructors are on the front lines of efforts to improve the safety record of the industry. This section addresses the scope of responsibilities for flight instructors and enumerates methods they can use to enhance their professional image and conduct.

Instructor Responsibilities

The job of a flight instructor, or any instructor, is to teach. The learning process can be made easier by helping students learn, providing adequate instruction, demanding adequate standards of performance, and emphasizing the positive. [Figure 10-1]

Figure 10-1. The four main responsibilities for flight instructors.

Helping Students Learn

Learning should be an enjoyable experience. By making each lesson a pleasurable experience for the student, the instructor can maintain a high level of student motivation. This does not mean the instructor must make things easy for the student or sacrifice standards of performance to please the student. The student experiences satisfaction from doing a good job or from successfully meeting the challenge of a difficult task.

Learning should be interesting. Knowing the objectives, in clear and concise terms, of each period of instruction gives meaning and interest to the student, as well as the instructor. Not knowing the objective of the lesson often leads to confusion, disinterest, and uneasiness on the part of the student.

Learning to fly should be a habit-building period during which the student devotes his or her attention, memory, and judgment to the development of correct habits. Any objective other than to learn the right way is likely to make students impatient. The instructor should keep the students focused on good habits both by example and by a logical presentation of learning tasks.

Providing Adequate Instruction

The flight instructor should attempt to carefully and correctly analyze the student’s personality, thinking, and ability. No two students are alike, and no one method of instruction can be equally effective for each student. The instructor must talk with a student at some length to learn about the student’s background interests, temperament, and way of thinking. The instructor’s methods also may change as the student advances through successive stages of training.

An instructor who has not correctly analyzed a student may soon find that the instruction is not producing the desired results. For example, this could mean that the instructor does not realize that a student is actually a quick thinker, but is hesitant to act. Such a student may fail to act at the proper time due to lack of self-confidence, even though the situation is correctly understood. In this case, instruction would obviously be directed toward developing student self-confidence, rather than drill on flight fundamentals. In another case, too much criticism may completely subdue a timid person, whereas brisk instruction may force a more diligent application to the learning task. A student may require instructional methods that combine tact, keen perception, and delicate handling. If such a student receives too much help and encouragement, a feeling of incompetence may develop.

Standards of Performance

Flight instructors must continuously evaluate their own effectiveness and the standard of learning and performance achieved by their students. The desire to maintain pleasant personal relationships with the students must not cause the acceptance of a slow rate of learning or substandard flight performance. It is a fallacy to believe that accepting lower standards to please a student produces a genuine improvement in the student-instructor relationship. An earnest student does not resent reasonable standards that are fairly and consistently applied.

Emphasizing the Positive

Flight instructors have a tremendous influence on their students’ perception of aviation. The way instructors conduct themselves, the attitudes they display, and the manner in which they develop their instruction all contribute to the formation of either positive or negative impressions by their student. The success of a flight instructor depends, in large measure, on the ability to present instruction so that a student develops a positive image of aviation.

Most new instructors tend to adopt those teaching methods used by their own instructors. These methods may or may not have been good. The fact that one has learned under one system of instruction does not mean that this is necessarily the best way it can be done, regardless of the respect one retains for the ability of their original instructor. Some students learn in spite of their instruction, rather than because of it. Emphasize the positive because positive instruction results in positive learning.

Flight Instructor Responsibilities

All flight instructors shoulder an enormous responsibility because their students ultimately fly an aircraft. Flight instructors have some additional responsibilities including the responsibility of evaluating student pilots and making a determination of when they are ready to solo. Other flight instructor responsibilities are based on Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations (14 CFR) part 61 and advisory circulars (ACs). [Figure 10-2]

Evaluation of Student Piloting Ability

Evaluation is one of the most important elements of instruction. In flight instruction, the instructor initially determines that the student understands the procedure or maneuver. Then the instructor demonstrates the maneuver, allows the student to practice the maneuver under direction, and finally evaluates student accomplishment by observing their performance.

Figure 10-2. The flight instructor has many additional responsibilities.

Evaluation of demonstrated ability during flight instruction must be based upon established standards of performance, suitably modified to apply to the student’s experience and stage of development as a pilot. The evaluation must consider the student’s mastery of all the elements involved in the maneuver, rather than merely the overall performance.

Correction of student errors should not include the practice of taking the controls away from students immediately when a mistake is made. Safety permitting, it is frequently better to let students progress part of the way into the mistake and find their own way out. It is difficult for students to learn to do a maneuver properly if they seldom have the opportunity to correct an error. On the other hand, students may perform a procedure or maneuver correctly and not fully understand the principles and objectives involved. When the instructor suspects this, students should be required to vary the performance of the maneuver slightly, combine it with other operations, or apply the same elements to the performance of other maneuvers. Students who do not understand the principles involved probably are not able to do this successfully.

Student Pilot Supervision

Flight instructors have the responsibility to provide guidance and restraint with respect to the solo operations of their students. This is by far the most important flight instructor responsibility because the instructor is the only person in a position to make the determination that a student is ready for solo operations. Before endorsing a student for solo flight, the instructor should require the student to demonstrate consistent ability to perform all of the fundamental maneuvers.

Practical Test Recommendations

Provisions are made on the airman certificate or rating application form for the written recommendation of the flight instructor who has prepared the applicant for the practical test involved. Signing this recommendation imposes a serious responsibility on the flight instructor. A flight instructor who makes a practical test recommendation for an applicant seeking a certificate or rating should require the applicant to thoroughly demonstrate the knowledge and skill level required for that certificate or rating. This demonstration should in no instance be less than the complete procedure prescribed in the applicable PTS.

A practical test recommendation based on anything less risks the presentation of an applicant who may be unprepared for some part of the actual practical test. In such an event, the flight instructor is logically held accountable for a deficient instructional performance. This risk is especially great in signing recommendations for applicants who have not been trained by the instructor involved. For balloons, 14 CFR part 61 requires a minimum of two training flights of one hour each with an authorized instructor within 60 days preceding the date of the test for a private or commercial certificate. The instructor signing the endorsement is required to have conducted the training in the applicable areas of operation stated in the regulations and the PTS, and certifies that the person is prepared for the required practical test. In most cases, the conscientious instructor has little doubt concerning the applicant’s readiness for the practical test.

FAA inspectors and designated pilot examiners rely on flight instructor recommendations as evidence of qualification for certification, and proof that a review has been given of the subject areas found to be deficient on the appropriate knowledge test. Recommendations also provide assurance that the applicant has had a thorough briefing on the practical test standards and the associated knowledge areas, maneuvers, and procedures. If the flight instructor has trained and prepared the applicant competently, the applicant should have no problem passing the practical test.

The recommended format for log book endorsements may be found in the current version of AC 61-65; an extract of those relevant to balloon instruction may be found in Appendix E.

Self-Improvement

Professional flight instructors must never become complacent or satisfied with their own qualifications and abilities. They should be constantly alert for ways to improve their qualifications, effectiveness, and the services they provide to students. Flight instructors are considered authorities on aeronautical matters and are the experts to whom many pilots refer questions concerning regulations, requirements, and new operating techniques.

Sincerity

The professional instructor should be straightforward and honest. Attempting to hide some inadequacy behind a smokescreen of unrelated instruction makes it impossible for the instructor to command the respect and full attention of a student. Teaching an aviation student is based upon acceptance of the instructor as a competent, qualified teacher and an expert pilot. Any facade of instructor pretentiousness, whether it is real or mistakenly assumed by the student, immediately causes the student to lose confidence in the instructor and learning is adversely affected.

Acceptance of the Student

With regard to students, the instructor must accept them as they are, including all their faults and problems. The student is a person who wants to learn, and the instructor is a person who is available to help in the learning process. Beginning with this understanding, the professional relationship of the instructor with the student should be based on a mutual acknowledgement that the student and the instructor are important to each other, and that both are working toward the same objective.

Personal Appearance and Habits

Personal appearance has an important effect on the professional image of the instructor. Today’s aviation customers expect their instructors to be neat, clean, and appropriately dressed. Since the instructor is engaged in a learning situation, the attire worn should be appropriate to a professional status. [Figure 10-3]

Personal habits have a significant effect on the professional image. The exercise of common courtesy is perhaps the most important of these.

Demeanor

The attitude and behavior of the instructor can contribute much to a professional image. The professional image requires development of a calm, thoughtful, and disciplined, but not somber, demeanor.

The instructor should also present an attitude of enthusiasm, with respect to the training conducted, whether ground or flight. The enthusiasm expressed by the instructor is normally reflected in the student’s response to the training, and makes it a much more enjoyable experience for all parties concerned.

Safety Practices and Accident Prevention

The safety practices emphasized by instructors have a long lasting effect on students. Generally, students consider their instructor to be a model of perfection whose habits they

Figure 10-3. The flight instructor should always present a professional appearance.

attempt to imitate, whether consciously or unconsciously. The instructor’s advocacy and description of safety practices mean little to a student if the instructor does not demonstrate them consistently. For this reason, instructors must meticulously observe the safety practices being taught to students. A good example is the use of a checklist before takeoff. If a student pilot sees the flight instructor layout, inflate, and take off in a balloon without referring to a checklist, no amount of instruction in the use of a checklist convinces that student to faithfully use one when solo flight operations begin.

To maintain a professional image, a flight instructor must carefully observe all regulations and recognized safety practices during flight operations. An instructor who is observed to fly with apparent disregard for loading limitations or weather minimums creates an image of irresponsibility that many hours of scrupulous flight instruction can never correct. Habitual observance of regulations, safety precautions, and the precepts of courtesy enhances the instructor’s image of professionalism. Moreover, such habits make the instructor more effective by encouraging students to develop similar habits.

Proper Language

In aviation instruction, as in other professional activities, the use of profanity and obscene language leads to distrust or, at best, to a lack of complete confidence in the instructor. To many people, such language is actually objectionable to the point of being painful. The professional instructor must speak normally, without inhibitions, and develop the ability to speak positively and descriptively without excesses of language.

Also consider that the beginning aviation student is being introduced to new concepts and experiences and encountering new terms and phrases that are often confusing. At the beginning of the student’s training, and before each lesson during early instruction, the instructor should carefully define the terms and phrases to be used during the lesson. The instructor should then be careful to limit instruction to those terms and phrases, unless the exact meaning and intent of any new expression are explained immediately. In all cases, terminology should be explained to the student before it is used during instruction.

The Learning Process

To learn is to acquire knowledge or skill. Learning also may involve a change in attitude or behavior. Pilots need to acquire the higher levels of knowledge and skill, including the ability to exercise judgment and solve problems. The challenge for the flight instructor is to understand how people learn, and more importantly, to be able to apply that knowledge to the learning environment. [Figure 10-4]

Figure 10-4. Effective learning shares several common characteristics.

Definition of Learning

The ability to learn is one of the most outstanding human characteristics. Learning occurs continuously throughout a person’s lifetime. To define learning, it is necessary to analyze what happens to the individual. Thus, learning can be defined as a change in behavior as a result of experience. This can be physical and overt, or it may involve complex intellectual or attitudinal changes which affect behavior in more subtle ways. In spite of numerous theories and contrasting views, psychologists generally agree on many common characteristics of learning.

Characteristics of Learning

Flight instructors need a good understanding of the general characteristics of learning in order to apply them in a learning situation. If learning is a change in behavior as a result of experience, then instruction must include a careful and systematic creation of those experiences that promote learning. This process can be quite complex because, among other things, an individual’s background strongly influences the way that person learns. To be effective, the learning situation should contain the following four points:

- Learning is purposeful. Most people have definite ideas about what they want to do and achieve. Their goals are sometimes short term, involving a matter of days or weeks, while others may have goals carefully planned for a career or a lifetime. Each student, then, has specific intentions and goals. Learning, then, becomes a means to those goals.

Learning is a result of experience. A student can learn only from personal experience; therefore learning and knowledge cannot exist apart from a person. Even when observing or performing the same procedures, two people can react differently; they learn different things from it, according to the manner in which the event affects their individual needs.

- Learning is multifaceted. The learning process includes verbal elements, emotional elements, and problem-solving elements all taking place at once.

- Learning is an active process. The individual who wishes to be proficient at a particular task or skill should understand that they never stop learning.

Principles of Learning

Over the years, educational psychologists have identified several principles which seem generally applicable to the learning process. They provide additional insight into what makes people learn most effectively.

- Readiness—individuals learn best when they are ready to learn. However, they do not learn well if they see no reason for learning. Getting students ready to learn is usually the instructor’s responsibility. If students have a strong purpose, a clear objective, and a definite reason for learning something, they make more progress than if they lack motivation.

- Exercise—the principle of exercise states that those things most often repeated are best remembered. It is the basis of drill and practice. The human memory is fallible. The mind can rarely retain, evaluate, and apply new concepts or practices after a single exposure. Students learn by applying what they have been told and shown. Every time practice occurs, learning continues. The instructor must provide opportunities for students to practice and, at the same time, make sure that this process is directed toward a goal.

- Effect—based on the emotional reaction of the student. It states that learning is strengthened when accompanied by a pleasant or satisfying feeling, and that learning is weakened when associated with an unpleasant feeling. Experiences that produce feelings of defeat, frustration, anger, confusion, or futility are unpleasant for the student. If, for example, an instructor attempts to teach precision maneuvering during the first flight, the student is likely to feel inferior and be frustrated.

- Primacy—the state of being first, often creates a strong, almost unshakable, impression. For the instructor, this means that what is taught must be right the first time. For the student, it means that learning must be right. “Unteaching” is often more difficult than teaching. Every student should be started right. The first experience should be positive, functional, and lay the foundation for all that is to follow.

- Intensity—a vivid, dramatic, or exciting learning experience teaches more than a routine or boring experience. A student is likely to gain greater understanding of steep approaches or short-field, high wind landings by performing them rather than merely reading about them. The principle of intensity implies that a student learns more from the real thing than from a substitute.

- Recency—things most recently learned are best remembered. Conversely, the further a student is removed in time from a new factor in understanding, the more difficult it is to remember. Instructors recognize the principle of recency when they carefully plan a summary for a ground school lesson, a flight period, or a postflight critique.

How People Learn

Initially, all learning comes from perceptions which are directed to the brain by one or more of the five senses: sight, hearing, touch, smell, and taste. Psychologists have also found that learning occurs most rapidly when information is received through more than one of the senses. [Figure 10-5]

Figure 10-5. Most learning occurs through sight, but the combination of sight and hearing accounts for about 99 percent of all perception.

Perceptions

Perceiving involves more than the reception of stimuli from the five senses. Perceptions result when a person gives meaning to sensations. People base their actions on the way they believe things to be.

Real meaning comes only from within a person, even though the perceptions which evoke these meanings result from external stimuli. The meanings which are derived from perceptions are influenced not only by the individual’s experience, but also by many other factors. Knowledge of the factors which affect the perceptual process is very important to the flight instructor because perceptions are the basis of all learning.

Factions Which Affect Perception

There are several factors that affect an individual’s ability to perceive. Some are internal to each person and some are external.

- Physical organism—provides individuals with the perceptual sensors for perceiving the world around them.

- Basic need—a person’s basic need is to maintain and enhance the organized self. A person’s most pressing need is to preserve and perpetuate the self. To that end, an instructor must remember that anything asked of the student that may be interpreted by the student as endangering the self is resisted or denied.

- Goals and values—perceptions depend on one’s goals and values. The precise kinds of commitments and philosophical outlooks which the student holds are important for the instructor to know, since this knowledge assists in predicting how the student interprets experiences and instructions.

- Self-concept—a powerful determinant in learning. If a student’s experiences tend to support a favorable self-image, the student tends to remain receptive to subsequent experiences. A negative self-concept inhibits the perceptual processes which tend to keep the student from perceiving, effectively blocking the learning process.

- Time and opportunity—it takes time and opportunity to perceive. Learning some things depends on other perceptions which have preceded these learnings, and on the availability of time to sense and relate these new things to the earlier perceptions. Thus, sequence and time are necessary.

- Element of threat—does not promote effective learning. When confronted with a perceived threat, students tent to limit their attention to the threatening object or condition.

Insight

Insight involves the grouping of perceptions into meaningful groups of understanding. Creating insight is one of the instructor’s major responsibilities. To ensure that this does occur, it is essential to keep each student constantly receptive to new experiences and to help the student realize the way each piece relates to all other pieces of the total pattern of the task to be learned.

As perceptions increase in number and are assembled by the student into larger blocks of learning, they develop insight. As a result, learning becomes more meaningful and more permanent. Forgetting is less of a problem when there are more anchor points for tying insights together. It is a major responsibility of the instructor to organize demonstrations and explanations, and to direct practice, so that the student has better opportunities to understand the interrelationship of the many kinds of experiences that have been perceived. Pointing out the relationships as they occur, providing a secure and nonthreatening environment in which to learn, and helping the student acquire and maintain a favorable self-concept are key steps in fostering the development of insight.

Motivation

Motivation is probably the dominant force governing the student’s progress and ability to learn. Motivation may be positive or negative, tangible or intangible, subtle and difficult to identify, or it may be obvious.

Positive motivation is provided by the promise or achievement of rewards. These rewards may be personal or social; they may involve financial gain, satisfaction of the self-concept, or public recognition. Motivation which can be used to advantage by the instructor includes the desire for personal gain, the desire for personal comfort or security, the desire for group approval, and the achievement of a favorable self-image.

Negative motivation may engender fear, and be perceived by the student as a threat. While negative motivation may be useful in certain situations, characteristically it is not as effective in promoting efficient learning as positive motivation.

Positive motivation is essential to true learning. Negative motivation in the form of reproofs or threats should be avoided with all but the most overconfident and impulsive students. Slumps in learning are often due to declining motivation. Motivation does not remain at a uniformly high level. It may be affected by outside influences, such as physical or mental disturbances or inadequate instruction. The instructor should strive to maintain motivation at the highest possible level. In addition, the instructor should be alert to detect and counter any lapses in motivation.

Levels of Learning

Levels of learning may be classified in any number of ways. Four basic levels have traditionally been included in flight instructor training:

- Rote—the ability to repeat something back which was learned but not understood. An example of this may be the student who reads and can repeat back the applicable provision of 14 CFR section 91.119, Minimum Safe Altitudes, but has no concept of how this may affect their flight.

- Understanding—to comprehend or grasp the nature or meaning of something. Once a student has received proper instruction on performing a steep descent, and has some experience controlling the balloon in straight and level flight, he can consolidate those old and new perceptions into an insight on how to make a steep approach. At this point, the student has developed an understanding of the procedure for the steep approach.

- Application—the act of putting something to use that has been learned and understood. When the student understands the procedure for entering and performing a steep approach to the ground, has had the maneuver demonstrated, and has practiced the approach until consistency has been achieved, the student has developed the skill to apply what has been learned. This is a major level of learning, and one at which the instructor is too often willing to stop.

- Correlation—associating what has been learned, understood, and applied with previous or subsequent learning. The correlation level of learning, which should be the objective of aviation instruction, is that level at which the student becomes able to associate an element which has been learned with other segments or blocks or learning.

Most training is conducted in such a manner that the student never progresses past the rote and understanding levels. This is an unacceptable procedure, as practical testing requires the student to perform at the application and correlation levels. Failing to bring the student to those levels is incomplete instruction, and does not provide a complete training experience.

Transfer of Learning

During a learning experience, the student may be aided by things learned previously. On the other hand, it is sometimes apparent that previous learning interferes with the current learning task. Consider the learning of two skills. If the learning of skill A helps to learn skill B, positive transfer occurs. If learning skill A hinders the learning of skill B, negative transfer occurs. It should be noted that the learning of skill B may affect the retention or proficiency of skill A, either positively or negatively. While these processes may help substantiate the interference theory of forgetting, they are still concerned with the transfer of learning.

Many aspects of teaching profit by this type of transfer. It may explain why students of apparently equal ability have differing success in certain areas. Negative transfer may hinder the learning of some; positive transfer may help others. This points to a need to know a student’s past experience and what has already been learned. In lesson and syllabus development, instructors should plan for transfer of learning by organizing course materials and individual lesson materials in a meaningful sequence. Each phase should help the student learn what is to follow.

Habit Formation

The formation of correct habits from the beginning of any learning process is essential to further learning and for correct performance after the completion of training. Remember that primacy is one of the fundamental principles of learning. Therefore, it is the instructor’s responsibility to insist on correct techniques and procedures from the outset of training to provide proper habit patterns. It is much easier to foster proper habits from the beginning of training than to correct faulty ones later.

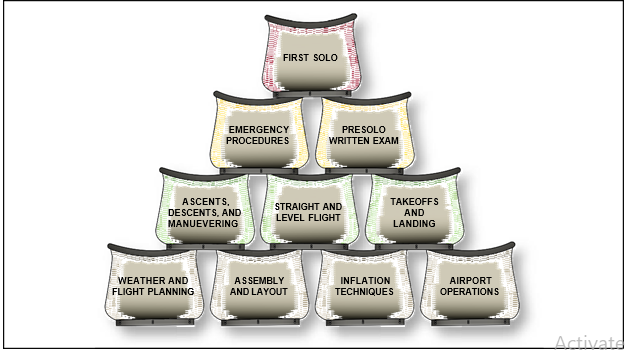

Due to the high level of knowledge and skill required in aviation for pilots, training has traditionally followed a building block concept. This means new learning and habits are based on a solid foundation of experience and/or old learning. As knowledge and skill increase, there is an expanding base upon which to build for the future.

Theories of Forgetting

A consideration of why people forget may point the way to help them remember. Several theories account for forgetting, including disuse and interference.

Disuse

The theory of disuse suggests that a person forgets those things which are not used. The high school or college graduate is saddened by the lack of factual data retained several years after graduation. Since the things which are remembered are those used on the job, a person concludes that forgetting is the result of disuse. But the explanation is not quite so simple. Experimental studies show that a hypnotized person can describe specific details of an event which normally is beyond recall. Apparently the memory is there, locked in the recesses of the mind. The difficulty is summoning it up to consciousness.

Interference

The basis of the interference theory is that people forget something because a certain experience has overshadowed it, or that the learning of similar things has intervened. This theory might explain how the range of experiences after graduation from school causes a person to forget or to lose knowledge. In other words, new events displace many things that had been learned. From experiments, at least two conclusions about interference may be drawn. First, similar material seems to interfere with memory more than dissimilar material; and second, material not well learned suffers most from interference.

The Teaching Process

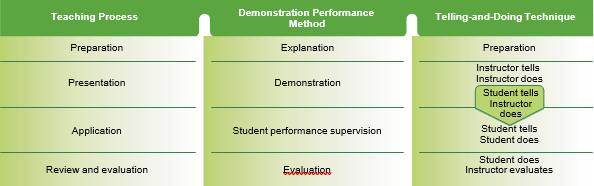

Effective teaching is based on principles of learning which have been previously discussed in this chapter. The learning process is not easily separated into a definite number of steps. Sometimes, learning occurs almost instantaneously, and other times it is acquired only through long, patient study and diligent practice. The teaching process, on the other hand, can be divided into steps. Although there is disagreement about the number of steps, examination of the various lists of steps in the teaching process reveals that different authors are saying essentially the same thing: the teaching of new material can be reduced to preparation, presentation, application, and review and evaluation. [Figure 10-6]

When beginning the teaching process, it may be helpful if the instructor remembers that in order to provide a “holistic,” or complete, approach to aviation training, it is necessary to teach more than just the “how-to” of flying. Too many times, the entire focus of flight training is spent on the mechanical aspects of performing a maneuver; it may be a better approach to also include and discuss the “why” of an action, to assist the student in gaining a better understanding of the flight process.

Preparation

For each lesson or instructional period, the instructor must prepare a lesson plan. Traditionally, this plan includes a

Figure 10-6. The teaching process consists of four basic principles.

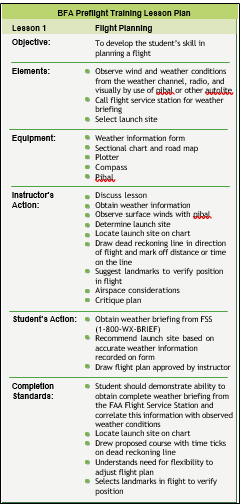

statement of lesson objectives, the procedures and facilities to be used during the lesson, the specific goals to be attained, and the means to be used for review and evaluation. The lesson plan should also include home study or other special preparation to be done by the student. The instructor should make certain that all necessary supplies, materials, and equipment needed for the lesson are readily available and that the equipment is operating properly. Preparation of the lesson plan may be accomplished after reference to the syllabus or practical test standards (PTS), or it may be in a preprinted form as prepared by a publisher of training materials. These documents list general objectives that are to be accomplished. Objectives are needed to bring the unit of instruction into focus. The instructor can organize the overall instructional plan by writing down the objectives and making certain that they flow in a logical sequence from beginning to end. The objectives allow the instructor to structure the training and permit the student to see clearly what is required along the way.

Performance-Based Objectives

One good way to write lesson plans is to begin by formulating performance-based objectives. The instructor uses the objectives as listed in the syllabus or the appropriate PTS as the beginning point for establishing performance-based objectives. These objectives are very helpful in delineating exactly what needs to be done and how it is done during each lesson. Once the performance-based objectives are written, most of the work of writing a final lesson plan is completed. One useful thought is the utilization of the “DAM principle”; objectives, as well as goals, should be difficult, attainable, and measurable.

Performance-based objectives are used to set measurable, reasonable standards that describe the desired performance of the student. This usually involves the term behavioral objective, although it may be referred to as a performance, instructional, or educational objective. All refer to the same thing, the behavior of the student.

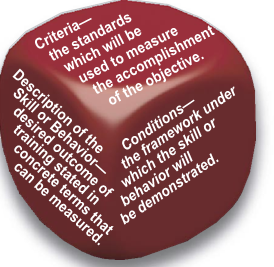

Performance-based objectives consist of three parts: description of the skill or behavior, conditions, and criteria. Each part is required and must be stated in a way that leaves every reader with the same picture of the objective, how it is performed, and to what level of performance. [Figure 10-7]

Use of performance-based objectives also provides the student with a better understanding of the big picture, as well as knowledge of exactly what is expected. This overview can alleviate a significant source of frustration on the part of the student.

Figure 10-7. Performance-based objectives are made up of a description of the skill or behavior, conditions, and criteria.

Presentation

Instructors have several methods of presentation from which to choose. The nature of the subject matter and the objective in teaching it normally determine the method of presentation.

The lecture method is suitable for presenting new material, for summarizing ideas, and for showing relationships between theory and practice. For example, it is suitable for the presentation of a ground school lesson on performance planning. This method is most effective when accompanied by instructional aids and training devices. In the case of a discussion on performance planning, a chalkboard, a marker board, or flip chart could be used effectively.

The demonstration-performance method is desirable for teaching a skill, such as instruction on most flight maneuvers. Showing a student pilot how to perform a steep descent, for example, would be appropriate for this method. The instructor would first demonstrate the maneuver, and then have the student attempt the same maneuver.

Another form of presentation is the guided discussion which is used in a classroom situation. It is a good method for encouraging active participation of the students. It is especially helpful in teaching subjects such as safety and emergency procedures where students can use initiative and imagination in addressing problem areas.

Review and Application

Application is where the student uses what the instructor has presented. After a classroom presentation, the student may be asked to explain the new material. The student also may be asked to perform a procedure or operation that has just been demonstrated. In most instructional situations, the instructor’s explanation and demonstration activities are alternated with student performance efforts. The instructor makes a presentation and then asks the student to try the same procedure or operation.

Usually the instructor has to interrupt the student’s efforts for corrections and further demonstrations. This is necessary, because it is very important that each student perform the maneuver or operation the right way the first few times. This is when habits are established. Faulty habits are difficult to correct and must be addressed as soon as possible. Flight instructors in particular must be aware of this problem since students do a lot of their practice without an instructor. Only after reasonable competence has been demonstrated should the student be allowed to practice certain maneuvers on solo flights. Then, the student can practice the maneuver again and again until correct performance becomes almost automatic. Periodic review and evaluation by the instructor is necessary to ensure that the student has not acquired any bad habits.

Teaching Methods

The information presented in previous sections has been largely theoretical, emphasizing concepts and principles pertinent to the learning process, human behavior, and effective communication in education and training programs. This knowledge, if properly used, enables instructors to be more confident, efficient, and successful. The discussion which follows departs from the theoretical with some specific recommendations for the actual conduct of the teaching process. Included are methods and procedures which have been tested and found to be effective.

Personal computers are a part of every segment of our society today. Since a number of computer-based programs are currently available from publishers of aviation training materials, a brief description of new technologies and how to use them effectively is provided near the end of this section.

Organizing Material

Regardless of the teaching method used, an instructor must properly organize the material. Lessons do not stand alone within a course of training. There must be a plan of action to lead instructors and their students through the course in a logical manner toward the desired goal. Usually the goal for students is a certificate or rating. A systematic plan of action requires the use of an appropriate training syllabus.

Generally, the syllabus must contain a description of each lesson, including objectives and completion standards.

Although instructors may develop their own syllabus, in practice many instructors use a group-developed syllabus such as that developed and available through the Balloon Federation of America. Thus, the main concern of the instructor usually is the more manageable task of organizing a block of training with integrated lesson plans. The traditional organization of a lesson plan is: introduction, development, and conclusion.

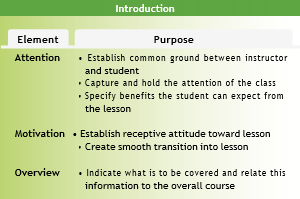

Introduction

The introduction sets the stage for everything to come. Efforts in this area pay great dividends in terms of quality of instruction. In brief, the introduction is made up of three elements—attention, motivation, and an overview of what is to be covered. [Figure 10-8]

Figure 10-8. The introduction prepares the students to receive the information in the lesson.

Attention

The purpose of the attention element is to focus each student’s attention on the lesson. The instructor may begin by telling a story, making an unexpected or surprising statement, asking a question, or telling a joke. Any of these may be appropriate at one time or another. Regardless of which is used, it should relate to the subject and establish a background for developing the learning outcomes. Telling a story or a joke that is not related in some way to the subject can only distract from the lesson. The main concern is to gain the attention of everyone and concentrate on the subject.

Motivation

The purpose of the motivation element is to offer the student specific reasons why the lesson content is important to know, understand, apply, or perform. For example, the instructor may talk about an occurrence where the knowledge in the lesson was applied. Or the instructor may remind the student of an upcoming test on the material. This motivation should appeal to each student personally and engender a desire to learn the material.

Overview

Every lesson introduction should contain an overview that explains what is to be covered during the period. A clear, concise presentation of the objective and the key ideas gives the students a road map of the route to be followed. A good visual aid can help the instructor show the students the path that they are to travel. The introduction should be free of stories, humor, or incidents that do not help the students focus their attention on the lesson objective. Also, the instructor should avoid a long apologetic introduction, because it only serves to dampen the students’ interest in the lesson.

Development

Development is the main part of the lesson. Here, the instructor develops the subject matter in a manner that helps the students achieve the desired learning outcomes. The instructor must logically organize the material to show the relationships of the main points. The instructor usually shows these primary relationships by developing the main points in one of the following ways: from past to present, simple to complex, known to unknown, and most frequently used to least frequently used.

Under each main point in a lesson, the subordinate points should lead naturally from one to the other. With this arrangement, each point leads logically into, and serves as a reminder of, the next. Meaningful transitions from one main point to another keep the students oriented, aware of where they have been, and where they are going. This permits effective sorting or categorizing chunks of information in the working or short-term memory. Organizing a lesson so the students grasp the logical relationships of ideas is not an easy task, but it is necessary if the students are to learn and remember what they have learned. Poorly organized information is of little or no value to the student because it cannot be readily understood or remembered.

Conclusion

An effective conclusion retraces the important elements of the lesson and relates them to the objective. This review and wrap-up of ideas reinforces student learning and improves the retention of what has been learned. New ideas should not be introduced in the conclusion because at this point they are likely to confuse the students. By organizing the lesson material into a logical format, the instructor has maximized the opportunity for students to retain the desired information. However, each teaching situation is unique. The setting and purpose of the lesson determines which teaching method—lecture, guided discussion, demonstration-performance, cooperative or group learning, computer-based training, or a combination—is used.

Lecture Method

The lecture method is the most widely used form of presentation. Every instructor should know how to develop and present a lecture. [Figure 10-9] Lectures are used for introduction of new subjects, summarizing ideas, showing relationships between theory and practice, and reemphasizing main points. The lecture method is adaptable to many different settings, including either small or large groups. Lectures also may be used to introduce a unit of instruction or a complete training program. Finally, lectures may be combined with other teaching methods to give added meaning and direction.

Figure 10-9. Instructors should try a dry run with another instructor to get a feel for the lecture presentation.

The lecture method of teaching needs to be very flexible since it may be used in different ways. For example, there are several types of lectures such as the illustrated talk where the speaker relies heavily on visual aids to convey ideas to the listeners. With a briefing, the speaker presents a concise array of facts to the listeners who normally do not expect elaboration of supporting material. During a formal lecture, the speaker’s purpose is to inform, to persuade, or to entertain with little or no verbal participation by the students. When using a teaching lecture, the instructor plans and delivers an oral presentation in a manner that allows some participation by the students and helps direct them toward the desired learning outcomes.

Demonstration-Performance Method

This method of teaching is based on the simple, yet sound principle that we learn by doing. Students learn physical or mental skills by actually performing those skills under supervision. An individual learns to write by writing, and to fly a balloon by actually performing flight maneuvers. Students also learn mental skills, such as speed reading, by this method. Skills requiring the use of tools, machines, and equipment are particularly well suited to this instructional method.

Every instructor should recognize the importance of student performance in the learning process. Early in a lesson that is to include demonstration and performance, the instructor should identify the most important learning outcomes. Next, explain and demonstrate the steps involved in performing the skill being taught. Then, allow students time to practice each step, so they can increase their ability to perform the skill.

The demonstration-performance method of teaching has five essential phases:

- Explanation Phase—explanations must be clear, pertinent to the objectives of the particular lesson to be presented, and based on the known experience and knowledge of the student. In addition to the necessary actions to be performed, the instructor should describe the end result of these efforts.

- Demonstration Phase—the instructor must show the student the actions necessary to perform a skill.

- Student Performance and Instructor Supervision Phases—these two phases, which involve separate actions, are performed concurrently, and are thus described under a single heading. The first action is the performance by the student of the physical or mental skill that had been explained. The second is the instructor’s supervision, insuring that errors are immediately corrected to standards already prescribed.

- Evaluation Phase—in this final phase, the instructor judges student performance. The student performs whatever competence has been attained, and the instructor evaluates and discovers just how well the skill has been learned. Form this measurement of student achievement, the instructor determines the effectiveness of the instruction.

Computer-based Training

Many new and innovative training technologies are available today. One of the most significant is computer-based training (CBT)—the use of the personal computer as a training device. [Figure 10-10] CBT is sometimes called computer-based instruction (CBI). The terms CBT and CBI are synonymous and may be used interchangeably.

Figure 10-10. The instructor must continually monitor student performance when using CBT, as with all instructional aids

Common examples of CBT with specific application to balloon flight training include the computer versions of the test prep study guides which are useful for preparation for the FAA knowledge tests. These programs typically allow the students to select a test, complete the questions, and find out how they did on the test. The student may then conduct a review of questions missed. An excellent resource for balloon training is the web site webexams.com; this provides the student with the ability to take practice exams, which assists in determining weaknesses in training.

While computers provide many training advantages, they also have limitations. Improper or excessive use of CBT should be avoided. Computer-based training should not be used by the instructor as stand-alone training any more than a textbook or video. Like video or a textbook, CBT is an aid to the instructor. The instructor must be actively involved with the students when using instructional aids. This involvement should include close supervision, questions, examinations, quizzes, or guided discussions on the subject matter.

Techniques of Flight Instruction

In this section, the demonstration-performance method is applied to the telling-and-doing technique of flight instruction, as well as the integrated technique of flight instruction.

The Telling-and-Doing Technique

This technique has been in use for a long time and is very effective in teaching physical skills. Flight instructors find it valuable in teaching procedures and maneuvers. The telling-and-doing technique is actually a variation of the demonstration-performance method. In the telling-and-doing technique, the first step is preparation. This is particularly important in flight instruction because of the introduction of new maneuvers or procedures. The flight instructor needs to be well prepared and highly organized if complex maneuvers and procedures are to be taught effectively. The student must be intellectually and psychologically ready for the learning activity. The preparation step is accomplished prior to the flight lesson with a discussion of lesson objectives and completion standards, as well as a thorough preflight briefing. [Figure 10-11]

Instructor Tells-Instructor Does

Presentation is the second step in the teaching process. It is a continuation of preparing the student, which began in the detailed preflight discussion, and now continues by a carefully planned demonstration and accompanying verbal explanation of the procedure or maneuver. It is important that the demonstration conforms to the explanation as closely as possible. In addition, it should be demonstrated in the same sequence in which it was explained to avoid confusion and provide reinforcement.

Student Tells-Instructor Does

This is a transition between the second and third steps in the teaching process. It is the most obvious departure from the demonstration-performance technique, and may provide the most significant advantages. In this step, the student actually plays the role of instructor, telling the instructor what to do and how to do it. Two benefits accrue from this step. First, being freed from the need to concentrate on performance of the maneuver and from concern about its outcome, the student should be able to organize his or her thoughts regarding the steps involved and the techniques to be used. In the process of explaining the maneuver as the instructor performs it, perceptions begin to develop into insights. Mental habits begin to form with repetition of the instructions previously received. Second, with the student doing the talking, the instructor is able to evaluate the student’s understanding of the factors involved in performance of the maneuver.

Student Tells-Student Does

Application is the third step in the teaching process. This is where learning takes place and where performance habits are formed. If the student has been adequately prepared (first step) and the procedure or maneuver fully explained and demonstrated (second step), meaningful learning occurs. The instructor should be alert during the student’s practice to detect any errors in technique and to prevent the formation of faulty habits.

Figure 10-11. Comparison of steps in the teaching process, the demonstration-performance method, and the telling-and-doing technique. This comparison shows the similarities, as well as some differences. The main difference in the telling-and-doing technique is the important transition, student tells—instructor does, which occurs between the second and third step.

At the same time, the student should be encouraged to think about what to do during the performance of a maneuver, until it becomes habitual. In this step, the thinking is done verbally. This focuses concentration on the task to be accomplished, so that total involvement in the maneuver is fostered.

Student Does-Instructor Evaluates

The fourth step of the teaching process is review and evaluation. In this step, the instructor reviews what has been covered during the instructional flight and determines to what extent the student has met the objectives outlined during the preflight discussion. Since the student no longer is required to talk through the maneuver during this step, the instructor should be satisfied that the student is well prepared and understands the task before starting. This last step is identical to the final step used in the demonstration- performance method. The instructor observes as the student performs, then makes appropriate comments.

At the conclusion of the evaluation phase, record the student’s performance and verbally advise each student of the progress made toward the objectives. Regardless of how well a skill is taught, there may still be failures. Since success is a motivating factor, instructors should be positive in revealing results. When pointing out areas that need improvement, offer concrete suggestions that help. The instructor should make every effort to end the evaluation on a positive note.

Critique and Evaluation

Since every student is different and each learning situation is unique, the actual outcome may not be entirely as expected. The instructor must be able to appraise student performance and convey this information back to the student. No skill is more important to an instructor than the ability to analyze, appraise, and judge student performance. The student quite naturally looks to the instructor for guidance, analysis, appraisal, as well as suggestions for improvement and encouragement. This feedback from instructor to student is called a critique.

In most cases, a critique should be conducted in private. It should come immediately after a student’s performance, while the details of the performance are easy to recall. An instructor may critique any activity which a student performs or practices to improve skill, proficiency, and learning.

Two common misconceptions about the critique should be corrected at the outset. First, a critique is not a step in the grading process. It is a step in the learning process. Second, a critique is not necessarily negative in content. It considers the good along with the bad, the individual parts, relationships of the individual parts, and the overall performance. A critique can, and usually should, be as varied in content as the performance being critiqued.

Purpose of a Critique

A critique should provide the student with something constructive upon which he or she can work or build. It should provide direction and guidance to raise their level of performance. Students must understand the purpose of the critique; otherwise, they are unlikely to accept the criticism offered and little improvement will result.

Methods of Critique

The critique of student performance is always the instructor’s responsibility, and it can never be delegated in its entirety. The instructor can add interest and variety to the criticism through the use of imagination and by drawing on the talents, ideas, and opinions of others. There are several useful methods of conducting a critique, two of which have specific application to balloon flight instruction.

Student-Led Critique

The instructor asks a student to lead the critique. The instructor can specify the pattern of organization and the techniques or can leave it to the discretion of the student leader. Because of the inexperience of the participants in the lesson area, student-led critiques may not be efficient, but they can generate student interest and learning and, on the whole, be effective.

Self-Critique

A student is required to critique personal performance. Like all other methods, a self-critique must be controlled and supervised by the instructor. Whatever the methods employed, the instructor must not leave controversial issues unresolved, nor erroneous impressions uncorrected. The instructor must make allowances for the student’s relative inexperience. Normally, the instructor should reserve time at the end of the student critique to cover those areas that might have been omitted, not emphasized sufficiently, or considered worth repeating. One variant of this method is for the instructor to ask the student to name three negative aspects of the flight training period, and discuss corrective action. Then, the instructor asks for three positive aspects of the training. This also indicates to the instructor whether or not the student is able to analyze their performance, in relation to the standards sought.

Ground Rules for Critiquing

There are a number of rules and techniques to keep in mind when conducting a critique. The following list can be applied, regardless of the type of critiquing activity.

- Avoid trying to cover too much. A few well-made points usually is more beneficial than a large number of points that are not developed adequately.

- Allow time for a summary of the critique to reemphasize the most important things a student should remember.

- Never allow yourself to be maneuvered into the unpleasant position of defending criticism. If the criticism is honest, objective, constructive, and comprehensive, no defense should be necessary.

- If part of the critique is written, make certain that it is consistent with the oral portion.

Although, at times, a critique may seem like an evaluation, it is not. Both student and instructor should consider it as an integral part of the lesson. It normally is a wrap-up of the lesson. A good critique closes the chapter on the lesson and sets the stage for the next lesson.

Characteristics of an Effective Critique

In order to provide direction and raise the students’ level of performance, the critique must be factual and be aligned with the completion standards of the lesson. This, of course, is because the critique is a part of the learning process. Some of the requirements for an effective critique are shown in Figure 10-12.

- Objective—the effective critique is focused on student performance. It should be objective, and not reflect the personal opinions, likes, dislikes, and biases of the instructor. If a critique is to be objective, it must be honest; it must be based on the performance as it was, not as it could have been, or as the instructor and student wished that it had been.

- Flexible—the instructor needs to examine the entire performance of a student and the context in which it is accomplished. Sometimes a good student turns in a poor performance and a poor student turns in a good one. A friendly student may suddenly become hostile, or a hostile student may suddenly become friendly and cooperative. The instructor must fit the tone, technique, and content of the critique to the occasion, as well as the student. A critique should be designed and executed so that the instructor can allow for variables. An effective critique is one that is flexible enough to satisfy the requirements of the moment.

- Acceptable—before students willingly accept their instructor’s criticism, they must first accept the instructor. Students must have confidence in the instructor’s qualifications, teaching ability, sincerity, competence, and authority. If a critique is presented fairly, with authority, conviction, sincerity, and from a position of recognizable competence, the student probably accepts it as such. Instructors should not rely on their position to make a critique more acceptable to their students.

Figure 10-12. Elements of an effective critique.

- Comprehensive—a comprehensive critique is not necessarily a long one, nor must it treat every aspect of the performance in detail. The instructor must decide whether the greater benefit comes from a discussion of a few major points or a number of minor points. The instructor might critique what most needs improvement, or only what the student can reasonably be expected to improve. An effective critique covers strengths as well as weaknesses.

- Constructive—a critique is pointless unless the student profits from it. The instructor should give positive guidance for correcting the fault and strengthening the weakness. Negative criticism that does not point toward improvement or a higher level of performance should be omitted from a critique altogether.

- Organized—unless a critique follows some pattern of organization, a series of otherwise valid comments may lose their impact. Almost any pattern is acceptable as long as it is logical and makes sense to the student as well as to the instructor. An effective organizational pattern might be the sequence of the performance itself. Sometimes a critique can profitably begin at the point where a demonstration failed and work backward through the steps that led to the failure.

- Thoughtful—an effective critique reflects the instructor’s thoughtfulness toward the student’s need for self-esteem, recognition, and approval from others. The instructor should never minimize the inherent dignity and importance of the individual. Ridicule, anger, or fun at the expense of the student have no place in a critique. While being straightforward and honest, the instructor should always respect the student’s personal feelings.

- Specific— the instructor’ s comments and recommendations should be specific, rather than general. The student needs to focus on something concrete. If the instructor has a clear, well-founded, and supportable idea in mind, it should be expressed with firmness and authority in terms that cannot be misunderstood.

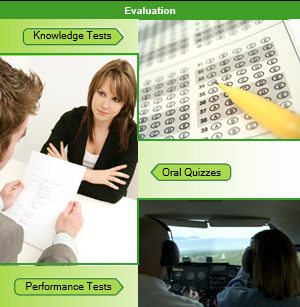

Evaluation

Whenever learning takes place, the result is a definable, observable, measurable change in behavior. The purpose of an evaluation is to determine how a student is progressing in the course. Evaluation is concerned with defining, observing, and measuring or judging this new behavior. Evaluation normally occurs before, during, and after instruction; it is an integral part of the learning process. During instruction, some sort of evaluation is essential to determine what the student is learning and how well they are learning it. The instructor’s evaluation may be the result of observations of the students’ overall performance, or it may be accomplished as either a spontaneous or planned evaluation, such as an oral quiz, written test, or skill performance test. [Figure 10-13]

Figure 10-13. There are three common types of evaluations that instructors may use.

Oral Quizzes

The most used means of evaluation is the direct or indirect oral questioning of the student by the instructor. Questions may be loosely classified as fact questions and thought questions. The answer to a fact question is based on memory or recall. This type of question usually concerns who, what, when, and where. Thought questions usually involve why or how, and require the student to combine knowledge of facts with an ability to analyze situations, solve problems, and arrive at conclusions. Proper quizzing by the instructor can have a number of desirable results.

Characteristics of Effective Questions

An effective oral quiz requires some preparation. The instructor should devise and write pertinent questions in advance. One method is to place them in the lesson plan. Prepared questions merely serve as a framework, and as the lesson progresses, should be supplemented by such impromptu questions as the instructor considers appropriate. To be effective, questions must apply to the subject of instruction. Unless the question pertains strictly to the particular training being conducted, it serves only to confuse the students and divert their thoughts to an unrelated subject. An effective question should be brief and concise, but also clear and definite.

Effective questions must be adapted to the ability, experience, and stage of training of the students. Effective questions center on only one idea. A single question should be limited to who, what, when, where, how, or why, not a combination. Effective questions must present a challenge to the students. Questions of suitable difficulty serve to stimulate learning. Effective questions demand and deserve the use of proper English.

Answering Questions from Students

Responses to student questions must also conform with certain considerations if answering is to be an effective teaching method. The question must be clearly understood by the instructor before an answer is attempted. The instructor should display interest in the student’s question and frame an answer that is as direct and accurate as possible. After the instructor completes a response, it should be determined whether or not the student’s request for information has been completely answered, and if the student is satisfied with the answer.

Occasionally, a student asks a question that the instructor cannot answer. In such cases, the instructor should freely admit not knowing the answer, but should promise to get the answer or, if practicable, offer to help the student look it up in available references.

Written Tests

As evaluation devices, written tests are only as good as the knowledge and proficiency of the test writer. This section is intended to provide the flight instructor with only the basic concepts of written test design.

Characteristics of a Good Test

A test is a set of questions, problems, or exercises for determining whether a person has a particular knowledge or skill. A test can consist of just one test item, but it usually consists of a number of test items. A test item measures a single objective and calls for a single response. The test could be as simple as the correct answer to an essay question or as complex as completing a knowledge or practical test. Regardless of the underlying purpose, effective tests share certain characteristics. For a full list of these characteristics, refer to the Aviation Instructor’s Handbook.

Test Development

When testing aviation students, the instructor is usually concerned more with criterion-referenced testing than norm- referenced testing. Criterion-referenced testing evaluates each student’s performance against a carefully written, measurable, standard or criterion. Norm-referenced testing measures a student’s performance against the performance of other students. There is little or no concern about the student’s performance in relation to the performance of other students. The FAA knowledge and practical tests for pilots are all criterion referenced because in aviation training it is necessary to measure student performance against a high standard of proficiency consistent with safety.

Presolo Knowledge Tests

Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations (14 CFR) part 61 requires the satisfactory completion of a presolo knowledge test prior to solo flight. The presolo knowledge test is required to be administered, graded, and all incorrect answers reviewed by the instructor providing the training prior to endorsing the student pilot certificate and logbook for solo flight. The regulation states that the presolo knowledge test must include questions applicable to 14 CFR parts 61 and 91 and on the flight characteristics and operational limitations of the make and model aircraft to be flown.

The content and number of test questions are to be determined by the flight instructor. An adequate sampling of the general operating rules should be included. In addition, a sufficient number of specific questions should be asked to ensure the student has the knowledge to safely operate the aircraft in the local environment.

Specific procedures for developing test questions are covered in the Aviation Instructor’s Handbook, but a review of some items as they apply to the presolo knowledge test are in order. Though selection-type (usually referred to as multiple- choice) test items are easier to grade, it is recommended that supply-type (or “fill in the blank”) test items be used for the portions of the presolo knowledge test where specific knowledge is to be tested. One problem with supply-type test items is difficulty in assigning the appropriate grade.

Since solo flight requires a thorough working knowledge of the different conditions likely to be encountered on the solo flight, it is important that the test properly evaluate this area. In this way, the instructor can see any areas that are not adequately understood and can then cover them in the review of the test. Selection-type test items do not allow the instructor to evaluate the student’s knowledge beyond the immediate scope of the test items. The supply-type test item measures much more adequately the knowledge of the student, and lends itself very well to presolo testing.

The instructor must keep a record of the test results for at least three (3) years, as required by the provisions of 14 CFR section 61.189. The record should at least include the date, name of the student, and the results of the test.

Performance Tests

The flight instructor does not administer the practical test for a pilot certificate. Flight instructors do get involved with the same skill or performance testing that is measured in these tests. Performance testing is desirable for evaluating training that involves an operation, a procedure, or a process. The job of the instructor is to prepare the student to take these tests. Therefore, each element of the practical test has been evaluated prior to an applicant taking the practical exam.

The purpose of the practical test standards (PTS) is to delineate the standards by which FAA inspectors and designated pilot examiners conduct tests for ratings and certificates. The standards are in accordance with the requirements of 14 CFR parts 61 and 91 and other FAA publications including the Aeronautical Information Manual and pertinent advisory circulars and handbooks. The objective of the PTS is to ensure the certification of pilots at a high level of performance and proficiency, consistent with safety.

Since every task in the PTS may be covered on the check ride, the instructor must evaluate all of the tasks before certifying the applicant to take the practical test. While this evaluation is not totally formal in nature, it should adhere to criterion-referenced testing. Although the instructor should always train the student to the very highest level possible, the evaluation of the student is only in relation to the standards listed in the PTS. The instructor, and the examiner, should also keep in mind that the standards are set at a level that is already very high. They are not minimum standards and they do not represent a floor of acceptability. In other words, the standards are the acceptable level that must be met and there are no requirements to exceed them.

Planning Instructional Activities

Any instructional activity must be well planned and organized if it is to proceed in an effective manner. Much of the basic planning necessary for the flight instructor is provided by the knowledge and proficiency requirements published in 14 CFR, approved school syllabi, and the various texts, manuals, and training courses available. This section reviews the planning required by the instructor as it relates to four key topics—course of training, blocks of learning, training syllabus, and lesson plans.

Course of Training

In education, a course of training may be defined as a complete series of studies leading to attainment of a specific goal. The goal might be a certificate of completion, graduation, or an academic degree. For example, a student pilot may enroll in a private pilot certificate course, and upon completion of all course requirements, be awarded a graduation certificate.

Other terms closely associated with a course of training include curriculum, syllabus, and training course outline. In many cases, these terms are used interchangeably, but there are important differences.