Introduction

Bob, an aviation maintenance instructor, arrives thirty minutes before a scheduled class to prepare for the lesson he plans to present that day. A quick visual scan tells him the classroom has good lighting, the desks are in order, and the room presents a neat overall appearance. He places his lecture notes on the podium, checking to make sure they are all there and in the correct order. Then, he turns on the computer to ensure the components are working correctly. A quick run of his visual presentation reassures him this portion of his lecture is ready. Next, he counts the handouts he plans to distribute to the class. By now, learners are beginning to filter into the classroom. With his preparations complete, Bob is free to greet the learners, chat with them socially, or answer any questions they might have about the previous class.

Today’s class is Bob’s introductory lecture on aircraft weight and balance. Using a software program, he has created a presentation featuring examples of safety problems caused by out-of-balance aircraft. He uses these images to introduce the class to the importance of aircraft weight and balance in safe flying. Then, Bob teaches the class how to compute weight and balance for a generic aircraft. To reinforce the lecture, Bob divides the class into small groups and distributes handouts which contain sample weight and balance problems. Working as a group, the learners solve the first weight and balance problem. During this time, Bob and the learners freely discuss how to figure weight and balance for that particular aircraft. Once the problem is solved, Bob reiterates the steps used to calculate weight and balance. Now Bob assigns another problem to the learners to be solved independently in class. After each learner completes this assignment, Bob is confident they will be able to successfully complete the remaining three weight and balance problems as homework for the next class.

By using a combination of teaching methods and instructional aids, Bob achieves his instructional objective, which is for the learners to compute weight and balance. In order to present this lesson, Bob has taken the theoretical information presented in previous chapters—concepts and principles pertinent to human behavior, how people learn, and effective communication—into the classroom. He has turned this knowledge into practical methodology for teaching purposes. Drawing on previously discussed theoretical knowledge, this chapter discusses specific recommendations on how to teach aviation learners.

What is Teaching?

Teaching is to instruct or train. Teachers often complete some type of formal training, have specialized knowledge, have been certified or validated in some way, and adhere to a set of standards of performance. Defining a “good instructor” has proven more elusive, but in The Essence of Good Teaching (1985), psychologist Stanford C. Ericksen wrote “good teachers select and organize worthwhile course material, lead learners to encode and integrate this material in memorable form, ensure competence in the procedures and methods of a discipline, sustain intellectual curiosity, and promote how to learn independently.”

Process

The teaching process organizes the material an instructor wishes to teach in such a way that the learner can understand it. The teaching process consists of four steps: preparation, presentation, application, and assessment. Regardless of the teaching or training delivery method used, the overall sequence remains the same. Much research has been devoted to trying to discover what makes an effective instructor. This research has revealed that effective instructors come in many forms, but they know how to process four essential teaching steps mentioned above. [Figure 5-1]

The remainder of this chapter explores the qualities of effective teachers and the methods used for preparing, presenting applying, and assessing lesson material and covers various delivery methods in depth.

Essential Teaching Skills

Four essential skills good teachers have include:

- People skills

- Subject matter expertise

- Assessment skills

- Management skills

People Skills

Effective instructors relate well to people. Effective communication, discussed in Chapter 4, underlies people skills. It is important for instructors to remember:

⦁ Technical knowledge is useless if the instructor fails to communicate it effectively.

⦁ The two-way process of effective communication includes actively listening to the learner.

Figure 5-1. Aviation instructors organize course material and use procedures and methods that promote learning.

In the previous scenario, Bob uses the guided group discussion period to listen to his learners discuss the weight and balance problem. By listening to their discussion and questions, he can pinpoint problem areas and explain them more fully during the review of the solved problem.

People skills also include the ability to interact respectfully, pick up when learners are not following along, provide motivation, and adapt to the needs of the learner when necessary. Another important people skill used by effective instructors is to challenge learners intellectually while supporting their efforts. Effective instructors also display enthusiasm for their subject matter and express themselves clearly.

Subject Matter Expertise

A subject matter expert (SME) is a person who possesses a high level of expertise, knowledge, or skill in a particular area. For example, the instructor in the opening scenario is an aviation maintenance SME.

Effective instructors have a sincere interest in learning and professional growth. There are a number of professional development opportunities for aviation instructors, such as Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) seminars, industry conventions, professional organizations, and online classes. Networking with and observing other instructors and seeking mentoring from an experienced instructor to learn new strategies is also helpful. By being a lifelong learner, the aviation professional remains current in both aviation and education. This topic is explored more thoroughly in the section titled Professional Development found within Chapter 8 of this handbook: Instructor Responsibilities and Professionalism

Management Skills

Management skills generally include the ability to plan, organize, lead, and supervise. For the effective instructor, this translates into being able to plan, organize, and carry out a lesson. A well-planned lesson means the instructor is also practicing time management skills and ensures the time allocated for the lesson is used effectively.

To manage time well, it is important that an instructor plans how to use the time to achieve the lesson goals. This includes time for what needs to be done as well as time to handle the unexpected. It minimizes stress by not planning too much for the allotted time.

Time management also come into play for the aviation instructor who is teaching a class. Consider the opening scenario in which Bob arrived early for the class and ensured the classroom was ready by completing a series of tasks.

Another management skill that enhances the effectiveness of aviation instructors is supervision of the learners. For the flight instructor, this may entail overseeing the preflight procedures. For the maintenance instructor, this may mean monitoring a maintenance procedure. While it is important to provide hands-on tasks in the lesson plan to engage learners, it is also important to ensure the learners complete the tasks correctly.

Assessment Skills

In Chapter 3, The Learning Process, learning was defined as a change in the behavior as a result of experience. The behavior can be physical and overt, or it can be intellectual or attitudinal. This change is measurable and therefore can be assessed.

Assessment of learning is a complex process, and it is important to be clear about the purposes of the assessment. There are several points at which assessments can be made: before training, during training, and after training. Assessment of learning is another important skill of an effective instructor. [Figure 5-2] This topic is discussed in detail in Chapter 6, Assessment.

Figure 5-2. An effective instructor uses a variety of tools to evaluate how learners learn, as well as what they know.

Instructor’s Code of Ethics

While many of the characteristics of effective instructors discussed in the previous paragraphs hold true for any instructor, the aviation instructor has the added responsibility of molding an aviation citizen—a pilot or maintenance technician who will be an asset to the rest of the aviation community. The following code describes the concept of a good aviation citizen.

An aviation instructor needs to remember he or she is teaching a pilot or technician who should:

- Make safety the number one priority,

- Develop and exercise good judgment in making decisions,

- Recognize and manage risk effectively,

- Be accountable for his or her actions,

- Act with responsibility and courtesy,

- Adhere to prudent operating practices and personal operating parameters, and

- Adhere to applicable laws and regulations.

In addition, an aviation instructor needs to remember he or she is teaching a pilot who should:

- Seek proficiency in control of the aircraft,

- Use flight deck technology in a safe and appropriate way, 3. Be confident in a wide variety of flight situations, and

4. Be respectful of the privilege of flight.

These concepts are also part of the Flight Instructors Model Code of Conduct (FIMCC), designed to enhance flight and ground instructor safety and professionalism. Developed by a diverse team of aviation professionals and extensively peer-reviewed within the aviation community, the FIMCC offers a vision of excellence to help flight and ground instructors build professional relationships with their learners.

A formal code of conduct/ethics serves as a tool to promote safety, good judgment, ethical behavior, and personal responsibility—all components of professionalism. The code offers a vision of flight education excellence, and it recommends operating practices to improve the quality and safety of flight instruction. The FIMCC is one of several similar codes that can be found at www.secureav.com. such as the Aviator’s Model Code of Conduct and a Student Pilot’s Model Code of Conduct. The National Association of Flight Instructors (NAFI) and the Society of Aviation and Flight Educators (SAFE), as well as similar groups, also have a code of ethics for instructors posted on their websites.

Course of Training

In education, a course of training is a complete series of studies leading to attainment of a specific goal. The goal might be a certificate of completion, graduation, or an academic degree. For example, a learner pilot may enroll in a private pilot certificate course, and upon completion of all course requirements, be awarded a graduation certificate. A course of training also may be limited to something like the additional training required for operating high-performance airplanes.

Other terms closely associated with a course of training include curriculum, syllabus, and lesson plan.

A curriculum for pilot training usually includes courses for the various pilot certificates and ratings, while the curriculum for an aviation maintenance technician (AMT) addresses the subject areas described in Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations (14 CFR) part 147. A syllabus is a summary or outline of an individual course of study that generally contains multiple lessons. The syllabus contains a description of each lesson, including objectives and completion standards. In aviation, the term “training syllabus” is commonly used and in this context it is a step-by-step, building block progression of learning with provisions for regular review and assessments at prescribed stages of learning. [Figure 5-3] A lesson plan is a detailed plan for how a specific lesson will be conducted. It includes the lesson objectives, organization of material being covered, description of teaching aids, instruction and learner actions, and evaluation criteria and completions standards.

Figure 5-3. The syllabus defines the unit of training, states by objective what the learner is expected to accomplish during the unit of training, shows an organized plan for instruction, and dictates the assessment process for either the unit or stages of learning.

Preparation of a Lesson

A determination of objectives and standards precedes instruction. Although some schools and independent instructors may develop their own syllabus, in practice, many instructors use a commercially-developed syllabus. For the aviation instructor, the objectives listed in the syllabus are a beginning point for instruction.

Training Objectives and Standards

Aviation training involves two types of objectives: performance-based and decision-based. Performance-based objectives help define exactly what needs to be done and how it is done during each lesson. As the learner progresses through higher levels of performance and understanding, the instructor should shift the training focus to decision-based training objectives. Decision-based training objectives rely on a more dynamic training environment and are ideally suited to scenario-based training and teach aviation learners critical thinking skills, such as risk management and aeronautical decision-making (ADM).

As indicated in Chapter 3, The Learning Process, training objectives apply to all three domains of learning—cognitive (knowledge), affective (attitudes, beliefs, values), and psychomotor (physical skills). Objectives should incorporate the desired level of learning, and these level of learning objectives may apply to one or more of the three domains of learning. Since each domain includes several educational or skill levels, the instructor adapts training objectives to a specific performance level of knowledge or skill. Clearly defined training objectives that the learner understands are essential to the teaching process regardless of the teaching technique used.

Standards are closely tied to objectives since they include a description of the desired knowledge, behavior, or skill stated in specific terms, along with conditions and criteria. When a learner performs according to well-defined standards, evidence of learning is apparent. Standards should contain comprehensive examples of the desired learning outcomes, or behaviors. As indicated in Chapter 3, The Learning Process, standards for the level of learning in the cognitive and psychomotor domains are easily established. However, the design of standards to evaluate a learner’s level of understanding or overt behavior in the affective domain (attitudes, beliefs, and values) is more difficult.

The overall objective of an aviation training course is usually well established, and the general standards are included in various rules and related publications. For example, eligibility, knowledge, proficiency, and experience requirements for pilots and AMT learners are stipulated in the regulations, and the standards are published in the applicable Airman Certification Standards (ACS)/Practical Test Standards (PTS) or oral and practical tests (O&Ps). It should be noted that ACS/PTS and O&P standards are limited to the most critical job tasks. Certification tests do not represent an entire training syllabus.

A broad, overall objective of any pilot training course is to qualify the learner to be a competent, efficient, safe pilot for the operation of specific aircraft types under stated conditions. Similar objectives and standards are established for AMT learners. While the established criteria or standards to determine whether the training has been adequate use the 14 CFR certification requirements, professional instructors should not limit their objectives to meeting the minimum published requirements for pilot or AMT certification.

Successful instructors teach their learners not only how, but also why and when. By incorporating ADM and risk management into each lesson, the aviation instructor helps the learner understand, develop, and reinforce the decision-making process which ultimately leads to sound judgment and good decision-making skills.

Performance-Based Objectives

Performance-based objectives set measurable, reasonable standards describing the learner’s desired performance, and may be referred to as a behavioral, performance, instructional, or educational objective. All refer to the same thing, the behavior of the learner.

These objectives provide a way of stating the level of performance a learner needs to demonstrate before he or she progresses to the next stage of instruction. Again, the objectives should be clear, measurable, and repeatable and mean the same thing to any knowledgeable reader. The objectives should be written to avoid the fallibility of recall, interpretation, or loss of specificity with time.

Performance-based objectives consist of three elements: description of the skill or behavior, the conditions, and the criteria. Each part should be stated in a way that leaves every reader with the same picture of the objective, how it is performed, and at the level of performance. [Figure 5-4]

Description of the Skill or Behavior

The description of the skill or behavior explains the desired outcome of the instruction as a change in knowledge, skill, or attitude.

The skill or behavior should be in concrete and measurable terms. Phrases such as “knowledge of …” and “awareness of …” cannot be measured very well and should be avoided. Phrases like “able to select from a list of …” or “able to repeat the steps to …” are better because they describe something measurable.

Figure 5-4. Performance-based objectives are made up of a description of the skill or behavior, conditions, and criteria.

Conditions

Conditions explain the rules for demonstration of the skill. If the desired objective is to navigate from point A to point B, the objective, as stated, is not specific enough for all learners to do it in the same way. Information such as equipment, tools, reference material, and limiting parameters should be included. For example, inserting several conditions narrows the objective as follows:

“Using appropriate charts, a prepared flight log, and training aircraft, navigate from point A to point B while maintaining standard hemispheric altitudes.” Sometimes, in the process of reading the objective, someone might say, “But, what if …?” This is a good indication that the conditions are confusing and need clarification.

Criteria

Criteria are the standards that measure the accomplishment of the objective. Good criteria define performance so there can be no question whether or not the performance meets the objective. In the previous example, the criteria may include that navigation from point A to point B be accomplished within 5 minutes of the preplanned flight time and that en route altitude be maintained within 200 feet. The revised performance-based objective may now also include arrival at point B within 5 minutes of planned arrival time and cruise altitude should be maintained within 200 feet during the en route phase of the flight.” The alert reader has already noted that the conditions and criteria changed slightly during the development of these objectives. In real-world objective development, that is exactly the way it will occur. Conditions and criteria may be refined as necessary.

The Importance of the ACS in Aviation Training Curricula

ACS documents hold an important position in aviation training curricula because they supply the instructor with specific performance objectives based on the standards for the issuance of a particular aviation certificate or rating. [Figure 5-5] The FAA frequently reviews the ACS test Areas of Operation and Tasks to maintain their relevance to the current aviation environment. Test items included as part of a test or evaluation should be both content valid and criterion valid. Content validity means that a particular maneuver or procedure closely mimics what is required in actual flying. Criterion validity means that the completion standards for the test are reflective of acceptable standards.

For example, in flight training, content validity is reflected by a particular maneuver closely mimicking a maneuver required in actual flight, such as the learner pilot being able to recover from a power-off stall. Criterion validity means that the completion standards for the test are reflective of acceptable standards in actual flight. Thus, the learner pilot exhibits knowledge of all the elements involved in a power-off stall as listed in the ACS.

Figure 5-5. Examples of Airman Certification Standards.

As discussed in Chapter 3, The Learning Process, humans develop cognitive skills through active interaction with the world. This concept has led to the adoption of scenario-based training in many fields, including aviation. An effective aviation instructor uses the maneuver-based approach of the ACS but presents the objectives in a scenario situation.

It has been found that flight learners using SBT methods demonstrate flying skills equal to or better than those trained under the maneuver-based approach only. Of even more significance is that the same data also suggest that SBT learners demonstrate better decision-making skills than maneuver-based learners—most likely because their training occurred while performing realistic flight maneuvers and not artificial maneuvers designed only for teaching that maneuver.

The incorporation of SBT as part of the lesson is discussed in more detail later in this chapter, as well as in Chapter 7, Planning Instructional Activity.

Decision-Based Objectives

The design and use of decision-based objectives specifically develops pilot judgment and ADM skills. Improper pilot decisions cause a significant percentage of all accidents, and the majority of fatal accidents in aircraft. Decision-based objectives facilitate a higher level of learning and application. By using dynamic and meaningful scenarios, the instructor teaches the learner how to gather information and make informed, safe, and timely decisions.

Decision-based training is not a new concept. Experienced instructors have been using scenarios that require dynamic problem solving to teach cross-country operations, emergency procedures, and other flight skills for years.

Decision-based learning objectives and the use of flight training scenarios do not preclude traditional maneuver-based training. Rather, flight maneuvers are integrated into the flight training scenarios and conducted as they would occur in the real-world. Those maneuvers requiring repetition may still be taught during concentrated settings. However, once they are learned, they are integrated into realistic and dynamic flight situations.

Decision-based objectives are also important for the aviation instructor planning AMT training. An AMT uses ADM and risk management skills during the repair and maintenance of aircraft.

Other Uses of Training Objectives

Performance-based and decision-based objectives help an instructor design a complete lesson plan. An instructor can use the standards of assessment, objectives, conditions, and criteria to fashion many of the details on the lesson plan. For example, many of the objective components may be used to determine the elements of the lesson and the schedule of events. The equipment necessary and the instructor and learner actions anticipated during the lesson have also been specified. By listing the criteria for the training objectives, the instructor has already established the completion standards normally included as part of the lesson plan.

Use of training objectives also provides the learner with a better understanding of the big picture, as well as knowledge of what is expected. This overview can alleviate a significant source of uncertainty and frustration on the part of the learner.

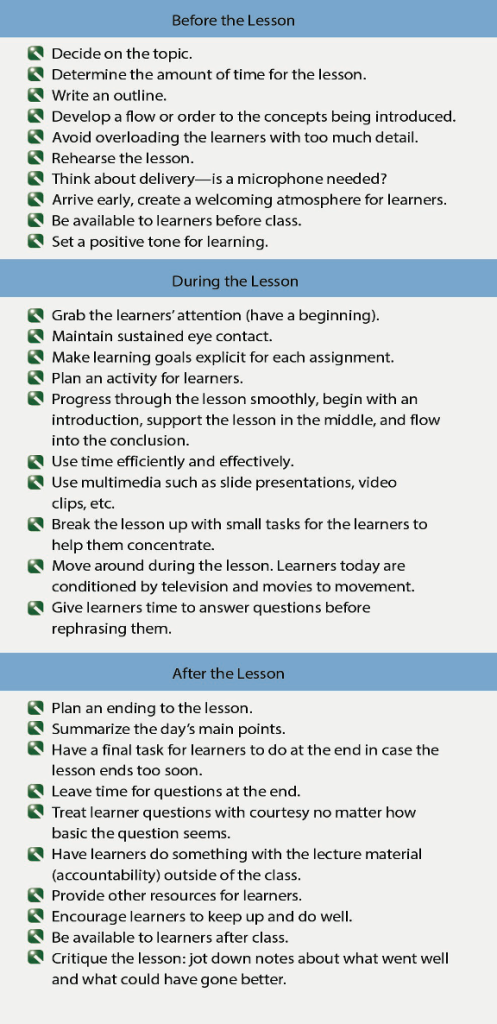

Presentation of a Lesson

How does an instructor keep the attention of a class? The steps in Figure 5-6 form a guideline for lesson presentation. Many of them can be combined during the actual presentation. For example, consider a video presentation given during the weight and balance lecture. The video adds a multimedia element to the lecture, is a good attention getter, and can visually demonstrate the learning objective.

Figure 5-6. Guidelines for presenting lessons.

Organization of Material

After determining objectives and standards, an instructor formulates a plan of action to lead learners through the course in a logical manner toward the desired goal. Usually, the goal for learners is a certificate or rating. It could be a private pilot certificate, an instrument rating, an AMT certificate or, other rating. In all cases, a systematic plan of action requires the use of an appropriate training syllabus. Generally, the syllabus contains a description of each lesson, including objectives and completion standards.

The main concern of the instructor is usually organizing a block of training with integrated lesson plans. The traditional organization of a lesson plan is introduction, development, and conclusion.

Lesson Introduction

The introduction sets the stage for everything to come. Efforts in this area pay great dividends in terms of quality of instruction. In brief, the introduction is made up of three elements: attention, motivation, and an overview.

Attention The purpose of the attention element is to focus each learner’s attention on the lesson. The instructor begins by telling a story, showing a video clip, asking a question, or telling a joke. Any of these may be appropriate at one time or another. Regardless of which is used, it should relate to the subject and establish a background for developing the learning outcomes. Telling a story or a joke unrelated in some way to the subject distracts from the lesson. The main concern is to focus everyone’s attention on the subject. [Figure 5-7]

Figure 5-7. The attention element causes learners to focus on the upcoming lesson.

Motivation

The motivation element offers the learners specific reasons why the lesson content is important to know, understand, apply, or perform and thus ensures readiness (Thorndike’s Law of Readiness). The instructor may provide examples where someone applied the knowledge or remind the learners of an upcoming assessment. The motivation should appeal to each learner personally and engender a desire to understand the material.

Overview

Every lesson introduction should contain an overview that tells the group what is to be covered during the period. A clear, concise presentation of the objective and the key ideas gives the learners a road map of the route to be followed. A good visual aid can help the instructor show the learners the path that they are to travel.

Development

Development is the main part of the lesson. Here, the instructor develops the subject matter in a manner that helps the learners achieve the desired outcomes. The instructor organizes the material logically to show the relationships of the main points. The instructor may show these primary relationships by developing the main points in one of the following ways: from past to present, simple to complex, known to unknown, and most frequently used to least used.

Past to Present

In this pattern of development, the subject matter is arranged chronologically, from the present to the past or from the past to the present. Time relationships are most suitable when history is an important consideration, as in tracing the development of radio navigation systems.

Simple-to-Complex

The simple-to-complex pattern helps the instructor lead the learner from simple facts or ideas to an understanding of the phenomena or concepts involved. When beginning a study of jet propulsion the learner might start by considering the forces involved when releasing air from a toy balloon and finish by taking part in a discussion of a complex gas turbine engine.

Do not be afraid to omit less important information at first in order to simplify the learning process. If Class D, E, and G airspace are the only airspace types being utilized by a learner, save the discussion of A, B, and C airspace until they have operating familiarity with the other types. Less information at first is easier to absorb.

Known to Unknown

By using something the learner already knows as the point of departure, the instructor can lead into new ideas and concepts. For example, when developing a lesson on heading indicators, the instructor could begin with a discussion of the magnetic compass before proceeding to a description of gyroscopic indicators.

Most Frequently Used to Least Used

In some subjects, certain information or concepts are common to all who use the material. This fourth organizational pattern starts with common usage before progressing to the rarer ones. Even though some aircraft are equipped with a computerized navigational system, instructors should begin by teaching learners the basics of navigation since all pilots use the basic skills.

Under each main point in a lesson, the subordinate points should lead naturally from one to another. With this arrangement, each point leads logically to and serves as a reminder of the next. Meaningful transition from one main point to another keeps the learners oriented, aware of where they have been, and where they are going. This permits learners to sort or categorize information in their working or short-term memory and allows them to process and remember what they have been taught.

Conclusion

An effective conclusion retraces the important elements of the lesson and relates them to the objective. This review and wrap-up of ideas reinforces learning and improves retention. New ideas should not be introduced in the conclusion because they are likely to confuse the learners

By organizing the lesson material into a logical format, the instructor maximizes the opportunity for learners to retain the desired information. Since each teaching situation is unique, the setting and purpose of the lesson determines which teaching method is used.

Training Delivery Methods

Today’s instructor can choose from a wealth of ways to present instructional material: lecture, discussion, guided discussion, problem based, group learning, demonstration-performance, or e-learning. In a typical lesson, an effective instructor normally uses a combination of methods. The instructor determines which teaching method best conveys the information and when to use it. For example, Bob lectures in the opening scenario, but after teaching how to compute weight and balance, he uses group learning to reinforce the lecture.

Lecture Method

In the lecture method, the instructor delivers knowledge via lectures to learners who are more or less silent participants. Lectures are best used when an instructor wishes to convey a general understanding of a subject. In general, lectures begin with an introduction of the topic to be discussed. The body of the lecture follows with a summary of the lecture’s main points at the end.

Lectures may introduce new subjects, summarize ideas, show relationships between theory and practice, and reemphasize main points. Thus, the lecture method is adaptable to many different settings, including small or large groups. Finally, lectures may be combined with other teaching methods to give added meaning and direction.

There are different varieties of lectures. During the illustrated talk, the speaker relies heavily on visual aids to convey ideas to the listeners. When using a briefing, the speaker presents a concise array of facts to the listeners who normally do not expect elaboration of supporting material. During a formal lecture, the speaker’s purpose is to inform, to persuade, or to entertain with little or no verbal participation by the learners. When using a teaching lecture, the instructor plans and delivers an oral presentation in a manner that allows some participation by the learners and helps direct them toward the desired learning outcomes.

Teaching Lecture

The teaching lecture is favored by aviation instructors because it allows some active participation by the learners. In other methods of teaching such as demonstration-performance or guided discussion, the instructor receives direct reaction from the learners, either verbally or by some form of body language. However in the teaching lecture, the feedback is not nearly as obvious and is much harder to interpret. An effective instructor develops a keen perception for subtle responses from the class—facial expressions, manner of taking notes, and apparent interest or disinterest in the lesson. The effective instructor is able to interpret the meaning of these reactions and adjust the lesson accordingly.

Preparing the Teaching Lecture

The following four steps should be followed in the planning phase of preparation:

- Establishing the objective and desired outcomes

- Researching the subject

- Organizing the material

- Planning productive classroom activities

While developing the lesson, the instructor also should strongly consider the use of examples and personal experiences related to the subject of the lesson. The instructor may support any point with meaningful examples, comparisons, statistics, or testimony.

After completing the preliminary planning and writing of the lesson plan, the instructor should rehearse the lecture to build selfconfidence. Rehearsals, or dry runs, help smooth out the mechanics of using notes, visual aids, and other instructional devices. If possible, the instructor should have another knowledgeable person or another instructor observe the practice sessions and act as a critic. This critique helps the instructor judge the adequacy of supporting materials and visual aids, as well as the overall presentation. [Figure 5-8]

Figure 5-8. Instructors should try a dry run with another instructor to get a feel for the lecture presentation.

Suitable Language

In the teaching lecture, simple rather than complex words should be used whenever possible. The instructor should not, use substandard English or errors in grammar.

If the subject matter includes technical terms, the instructor should clearly define each one so that no learner is in doubt about its meaning. Whenever possible, the instructor should use specific rather than general words. For example, the specific words, “a leak in the fuel line” tell more than the general term “discrepancy.”

Another way the instructor can add life to the lecture is to vary his or her tone of voice and pace of speaking. In addition, using sentences of different length helps, since consistent use of short sentences results in a choppy style. On the other hand, poorly constructed long sentences are difficult to follow and can easily become tangled. To ensure clarity and variety, the instructor should normally use sentences of short and medium length.

Types of Delivery

A good teaching lecture utilizes an extemporaneous technique. The instructor speaks from a mental or written outline, but does not read or memorize the material to be presented. Because the exact words to express an idea are spontaneous, the lecture is more personalized than one that is read or spoken from memory.

If the instructor realizes from puzzled expressions that a number of learners fail to grasp an idea, that point can be further elaborated until the reactions indicate they understand. The extemporaneous presentation reflects the instructor’s personal enthusiasm and is more flexible than other methods. For these reasons, it is likely to hold the interest of the learners.

Notes used wisely can ensure accuracy, jog the memory, and dispel the fear of forgetting. They are essential for reporting complicated information, and they may help keep the lecture on track. The instructor who requires notes should use them sparingly and unobtrusively but at the same time should make no effort to hide them from the learners. [Figure 5-9]

Figure 5-9. Notes allow the accurate dissemination of complicated information.

An informal lecture includes active learner participation. Learning is best achieved if learners participate actively in a friendly, relaxed atmosphere. The use of questions achieves active learner participation. In this way, the learners are encouraged to make contributions that supplement the lecture. However, it is the instructor’s responsibility to plan, organize, develop, and present the major portion of a lesson.

Advantages and Disadvantages of the Lecture A lecture is a convenient way to instruct large groups. If necessary, a public address system can be used to amplify the speaker’s voice. Lectures can be used to present information that would be difficult for the learners to get in other ways, particularly if they do not have the time required for research, or if they do not have access to reference material. Lectures supplement other teaching devices and methods. A brief introductory lecture can give direction and purpose to a demonstration or prepare learners for a discussion by telling them something about the subject matter to be covered.

In a lecture, the instructor can present many ideas in a relatively short time. Logically organized tasks and ideas can be presented concisely and in rapid sequence.

The lecture is particularly suitable for explaining any necessary background information. By using a lecture in this way, the instructor can offer learners with varied backgrounds a common understanding of essential principles and facts. However, lectures do not allow an instructor a precise measure of learner understanding of the material covered.

To achieve desired learning outcomes through the lecture method, an instructor needs considerable skill in speaking. As indicated in Chapter 3, The Learning Process, a learner’s rate of retention drops off significantly after the first 10-15 minutes of a lecture and improves at the end. Research has shown that learning is an active process—the more involved learners are in the process, the more they retain.

The lecture does not foster attainment of certain types of learning outcomes, such as motor skills, which need to be perfected via hands-on practice. Thus, an instructor who introduces some form of active learner participation in the middle of a lecture greatly increases retention.

Discussion Method

The discussion method modifies the pure lecture form by using lecture and then discussion to actively integrate the learner into the process. In the discussion method, the instructor provides a short lecture, which gives basic knowledge to the learners. This short lecture is followed by instructor-learner and learner- learner discussion.

This method relies on discussion and the exchange of ideas. Everyone has the opportunity to comment, listen, think, and participate. By being actively engaged in discussing the lecture, learners improve their recall and ability to use the information.

It is important for the instructor to keep the discussion focused on the subject matter. The instructor may need to initiate leading questions, comment on any disagreements, ensure that all learners participate, and summarize what has been learned.

Tying the discussion method into the lecture method not only provides active participation, it also allows learners to develop higher order thinking skills (HOTS). The give and take of the discussion method also helps learners evaluate ideas, concepts, and principles. When using this method, instructors should keep their own discussion to a minimum since the goal is learner participation.

Guided Discussion Method

Instructors can also use another form of discussion, the guided discussion method, to ensure the learner has correctly received and interpreted subject information. The learner needs a level of knowledge about the topic to be discussed, either through reading prior to class or a short lecture to set up the topic to be discussed. This training method employs instructor-guided discussion with the instructor maintains control of the discussion. It can be used during classroom periods and preflight and postflight briefings. The discussions reflect whatever level of knowledge and experience the learners have gained.

The goal of guided discussions is to draw out the knowledge of the learner. The greater the participation becomes, the more effective the learning will be. All members of the group should follow the discussion. The instructor should treat everyone impartially, encourage questions, exercise patience and tact, and comment on all responses with the goal of reinforcing a learning objective related to the lesson. The instructor acts as a facilitator to encourage discussion between learners without sarcasm.

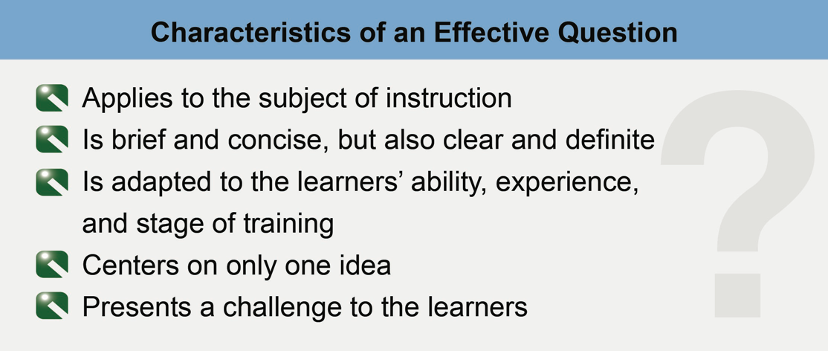

Use of Questions in a Guided Discussion

In the guided discussion, learning is achieved through the skillful use of questions. Questions can be categorized by function and characteristics.

The instructor often uses a lead-off question to open up an area for discussion. After the discussion develops, the instructor may ask a follow-up question to guide the discussion. The reasons for using a follow-up question may vary. The instructor may want a learner to explain something more thoroughly, or may need to bring the discussion back to a point from which it has strayed. An instructor may answer a question with a question and direct that question back to the person posing the question or other participant.

Questions are so much a part of teaching that they are often taken for granted. Effective use of questions may result in more learning than any other single technique used by instructors. Instructors should avoid questions that can be answered by short factual statements or yes or no responses and ask open-ended questions that are thought provoking and require more mental activity. Since most aviation training is at the understanding level or higher, questions should require learners to grasp concepts, explain similarities and differences, and to infer cause-and-effect relationships. [Figure 5-10]

Figure 5-10. If the objectives of a lesson are clearly established in advance, instructors will find it much easier to ask appropriate questions that keep the discussion moving in the planned direction.

Planning a Guided Discussion

Planning a guided discussion is similar to planning a lecture. (Note that the following suggestions include many that are appropriate for planning cooperative learning, to be discussed later in the chapter.)

⦁ Select an appropriate topic. Unless the learners have some knowledge to exchange with each other, they cannot reach the desired learning outcomes. If necessary, make assignments that give the learners an adequate background for discussing the lesson topic.

⦁ State the specific lesson objective at the understanding level of learning. Through discussion, the learners develop an understanding of the subject by sharing knowledge, experiences, and backgrounds. The desired learning outcomes should stem from the objective.

⦁ Conduct adequate research to become familiar with the topic. The instructor should always be alert for ideas that will enhance a lesson for a particular group of learners. Similarly, the instructor can consider any prediscussion assignment while conducting research for the classroom period. During this research process, the instructor should also earmark reading material that appears to be appropriate as background material for learners. Such material should be well organized and based on fundamentals.

⦁ Organize the main and subordinate points of the lesson in a logical sequence. The guided discussion has three main parts: introduction, discussion, and conclusion. The introduction consists of three elements: attention, motivation, and overview. During the discussion, the instructor should be certain that the main points discussed build logically with the objective. The conclusion consists of a summary of the main points. By organizing in this manner, the instructor phrases the questions to help the learners obtain a firm grasp of the subject matter and to minimize the possibility of a rambling discussion.

⦁ Plan at least one lead-off question for each desired learning outcome. While preparing questions, the instructor should remember that the purpose is to stimulate discussion, not merely to get answers. Lead-off questions should usually begin with how or why. For example, it is better to ask “Why does an aircraft normally require a longer takeoff run at Denver than at New Orleans?” instead of “Would you expect an aircraft to require a longer takeoff run at Denver or at New Orleans?” Learners can answer the second question by merely saying “Denver,” but the first question is likely to start a discussion of air density, engine efficiency, and the effect of temperature on performance.

Learner Preparation for a Guided Discussion It is the instructor’s responsibility to help learners prepare themselves for the discussion. Each learner should be encouraged to accept responsibility for contributing to the discussion and benefiting from it. Throughout the time the instructor prepares the learners for their discussion, they should be made aware of the lesson objective(s). In certain instances, the instructor has no opportunity to assign preliminary work. In such cases, it is practical and advisable to give the learners a brief general survey of the topic during the introduction. Normally, learners should not be asked to discuss a subject without some background in that subject.

Guiding a Discussion—Instructor Technique

The techniques used to guide a discussion require practice and experience. The instructor needs to keep up with the discussion and know when to intervene with questions or redirect the group’s focus. The following information provides a framework for successfully conducting the guided discussion.

Introduction

The introduction should include an attention element, a motivation element, and an overview of key points. To encourage enthusiasm and stimulate discussion, the instructor should create a relaxed, informal atmosphere. Each learner should be given the opportunity to discuss the various aspects of the subject, and feel free to do so. Moreover, the learner should feel a personal responsibility to contribute. The instructor should try to make the learners feel that their ideas and active participation are wanted and needed.

Discussion

The instructor opens the discussion by asking one of the prepared lead-off questions. Discussion questions should be easy for learners to understand and put forth decisively. While the instructor should have the answer in mind before asking the question, the learners need to think about the question before answering. It takes time for learners to recall data, determine how to answer, or to think of an example.

The more difficult the question, the more time the learners need to answer. If the instructor sees puzzled expressions, denoting that the learners do not understand the question, it should be rephrased in a slightly different form. The nature of the questions should be determined by the lesson objective and desired learning outcomes.

Once the discussion is underway, the instructor should listen attentively to the ideas, experiences, and examples contributed by the learners during the discussion. Remember that during the preparation, the instructor listed some of the anticipated responses that would, if discussed by the learners, indicate that they had a firm grasp of the subject. By using “how” and “why” follow-up questions, the instructor should be able to guide the discussion toward the objective of helping learners understand the subject.

After the learners discuss the ideas that support this particular part of the lesson, the instructor should summarize what they have accomplished using an interim summary. This usually occurs after the discussion of each learning outcome to bring ideas together and help in transition, showing how the discussion by the group related to and supported the objective. An interim summary reinforces learning in relation to a specific learning outcome. The interim summary may also be used to keep the group on the subject or to divert the discussion to another member.

Conclusion

A guided discussion closes by summarizing the material covered. The instructor ties together the various points or topics discussed, and shows the relationships between the facts brought forth and the practical application of these facts. For example, while concluding a discussion on density altitude, an instructor might describe an accident, which occurred due to a pilot attempting to take off at a high-altitude airport with a fully loaded aircraft on a hot day.

The summary should be succinct, but not incomplete. If the discussion has revealed that certain areas are not understood by one or more members of the group, the instructor should clarify or cover this material again.

Advantages

Training methods involving discussion encourage learners to listen to and learn from their instructor and each other. Open-ended questions during guided discussion leads to concepts of risk management and ADM. The use of “What If?” during the discussion calls for high-order thinking skills and exposes the learner to the decision-making process.

From the description of guided discussion, it is obvious this method works well in a group situation, but it can be modified for an interactive one-on-one learning situation. [Figure 5-11]

Figure 5-11. As the learner grows in flight knowledge, he or she should be able to lead the postflight review while the instructor guides the discussion with targeted questions.

Problem-Based Learning

In 1966, the McMaster University School of Medicine in Canada pioneered a new approach to teaching and curriculum design called problem-based learning (PBL). In the intervening years, PBL has helped shift the focus of learning from an instructor-centered approach to a learner-centered approach. There are many definitions for PBL, but this handbook defines it as a learning environment where lessons involve learners with problems encountered in real life and that ask them to find real-world solutions.

PBL starts with a carefully constructed problem to which there is no single solution. The benefit of PBL lies in helping the learner gain a deeper understanding of the information and in improving his or her ability to recall the information.

When presenting material as an authentic problem in a situated environment, the learner may “make meaning” of the information based on past experience and personal interpretation. This problem type encourages the development of HOTS, which include cognitive processes such as problem solving and decision-making, as well as the cognitive skills of analysis, synthesis and evaluation.

Developing good problems that motivate, focus, and initiate learning are an important component of PBL. Effective problems:

- Relate to the real-world so learners want to solve them.

- Require learners to make decisions.

- Are open-ended and not limited to one correct answer.

- Are connected to previously learned knowledge as well as new knowledge.

- Reflect lesson objective(s).

- Challenge learners to think critically.

Teaching Higher Order Thinking Skills (HOTS)

To teach the cognitive skills needed in making decisions and judgments effectively, an instructor should incorporate analysis, synthesis, and evaluation into lessons using PBL. HOTS should be taught throughout the curriculum from simple to complex and from concrete to abstract.

Basic approach to teaching HOTS:

- Set up the problem.

- Determine learning outcomes for the problem.

- Solve the problem or task.

- Reflect on problem-solving process.

- Consider additional solutions through guided discovery.

- Reevaluate solution with additional options.

- Reflect on this solution and why it could be the best solution.

- Consider what “best” means (Is it situational?).

Types of Problem-Based Instruction

A problem-based lesson usually involves an incentive or need to solve the problem. It includes a decision on how to find a solution, a possible solution, an explanation for the reasons used to reach that solution, and then reflection on the solution. A discussion of three types of problem-based instruction follow: scenario-based, collaborative problem-solving, and case study.

Scenario-Based Training Method (SBT)

SBT uses a highly structured script of real-world experiences to address aviation training objectives in an operational environment. It presents realistic situations that allow learners to rehearse mentally and explore practical application of various bits of knowledge. Pilot decisions cause a significant percentage of all accidents and the majority of fatal accidents, and SBT challenges the learner or transitioning pilot using a variety of flight scenarios with the goal of avoiding accidents. These scenarios require the pilot to manage the available resources, exercise sound judgment, and make timely decisions. Such training can include initial training, transition training, upgrade training, recurrent training, and special training. Since it has been documented that learners gain more knowledge when actively involved in the learning process, SBT is also used to train AMTs.

The scenario may not have one right or one wrong answer, which reflects situations faced in the real-world. It is important for the instructor to understand in advance which outcomes are positive and/or negative and give the learner freedom to make both good and poor decisions without jeopardizing safety. This allows the learner to make decisions that fit his or her experience level and result in positive outcomes.

Once the class has mastered the ability to compute weight and balance, Bob decides to give them a real-world scenario. A customer wants a tail strobe light installed on his Piper Cherokee 180. How will this installation affect the weight and balance of the aircraft?

The learners need to plan to remove the position light, install a power supply, and also install the tail strobe light. Then they need to consider all the actions and procedures that affect the final weight and balance of the aircraft. What if part of the assembly does not fit properly? The real-world problem forces the learner to analyze, evaluate, and make decisions about the procedures required.

For the flight instructor, a good scenario tells a story that begins with a reason to fly because a pilot’s decisions differ depending on the motivation to fly. For example, Mark and his college fraternity brothers bought tickets for a playoff game at their alma mater. Mark volunteered to fly all of them to the game in an airplane he rented. Another friend is planning to meet them at the airport and drive everyone to the game and back.

Mark has strong motivation to fly his friends to the game, so he checks the weather for College Airport which is reported as clear and unrestricted visibility. His flight is a go, yet, 15 miles from College Airport he descends to 1,000 feet to stay below the lowering clouds and encounters rain and lowering visibility to 3 miles. The terrain is flat farmland with no published obstacles. What will he do now?

Remember, a good inflight scenario is a learning experience. SBT is a powerful tool because the future is unpredictable and there is no way to train a pilot for every combination of events that may happen in the future. A good scenario:

- Is not a test;

- Will not have one right answer;

- Does not offer an obvious answer;

- Should not promote errors; and

- Should promote situational awareness and opportunities for decision-making.

Collaborative Problem-Solving Method

When using the collaborative problem-solving method, the instructor provides a problem to a group who then solves it. The instructor provides assistance when needed, but understands that learning to solve the problem without assistance is part of the learning process. This method can be modified for an interactive one-on-one learning situation such as an independent aviation instructor might encounter. The instructor provides the problem to the learner and participates in finding solutions by offering limited assistance as the learner solves it. Once again, open-ended “what if” problems encourage the learners an opportunity to develop HOTS.

Case Study Method

An increasingly popular form of teaching, the case study, contains a story relative to the learner that forces him or her to deal with situations encountered in real life. The instructor presents the case to the learners who then analyze it, come to conclusions, and offer possible solutions. Effective case studies require the learner to use critical thinking skills.

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) descriptions of aviation accidents provide an excellent source of real-world case studies for flight instructors. By removing the NTSB determination of probable cause, a flight instructor can use the description as a case study and allow the learners to discuss probable cause without bias. The learners analyze the information and suggest possible reasons for the accident. The instructor then shares the NTSB’s determination of probable cause, which can lead to further discussions of how to avoid this type of accident.

Electronic Learning (E-Learning)

Electronic learning or e-learning has become an umbrella term for any type of education that involves an electronic component. [Figure 5-12] E-learning comes in many formats. It can be a stand-alone software program that takes a learner from lecture to exam or it can be an interactive web-based course.

Time flexible, cost competitive, learner-centered, easily updated, accessible anytime and anywhere; e-learning has many advantages that make it a popular addition to the field of education.

E-learning is now used for training at many different levels. For example, technology flight training devices and flight simulators are used by everyone from flight schools to major airlines, as well as the military. Flight Schools of all types may offer training using a variety of computer-based desk top Basic Aviation Training Devices (BATDs), stand-alone, personal computer based advanced aviation training devices (AATDs) and even more advance Flight Training Devices (FTDs) for a portion of the time a pilot needs for various certificates and ratings. Major airlines have high-level flight simulators that are so realistic that transitioning crews meet all qualifications in the flight simulator. Likewise, military pilots use flight training devices or flight simulators to prepare for flying aircraft, such as the A-10, for which there are no two-seat training versions. With e-learning, sophisticated databases can organize vast amounts of information that can be quickly sorted, searched, found, and cross-indexed.

Figure 5-12. E-learning encompasses a variety of electronic educational media.

The active nature of e-learning enhances the overall learning process several ways. Well-designed programs allow learners to feel more in control of the content and how fast they learn it. They can explore areas of interest and discover more about a subject on their own. In addition, e-learning often seems more enjoyable than learning from a classroom lecture. Main advantages include less time spent on instruction compared to traditional classroom training, and a higher level of mastery and retention.

Distance learning, or the use of electronic media to deliver instruction when the instructor and learner are separated, is another advantage to e-learning. Participants in a class may be located on different continents, yet share the same teaching experience. Distance learning also may be defined as a system and process that connects learners with resources for learning. As sources for access to information expand, the possibilities for distance learning increase.

While e-learning has many training advantages, it also has limitations which can include the lack of peer interaction and personal feedback, depending on what method of e-learning is used. For the instructor, maintaining control of the learning situation may be difficult. It also may be difficult to find good programs for certain subject areas, and the expense associated with the equipment, software, and facilities need to be considered. In addition, instructors and learners may lack sufficient experience with specific programs to take full advantage of the software that is available.

Improper or excessive use of e-learning should be avoided. For example, a flight instructor should not rely exclusively on a software program on traffic patterns and landings to do the ground instruction for a learner pilot, and then expect the learner to demonstrate patterns and landings in the aircraft. Likewise, it would be unfair to expect a maintenance learner to safely and properly perform a compression check on an aircraft engine if he or she received only e-learning training.

Along with the many types of e-learning, there are a variety of terms used to describe the educational use of the computer. This handbook will use the term “computer-assisted learning” in the following discussion.

Computer-Assisted Learning (CAL) Method

Computer-assisted learning (CAL) couples the personal computer (PC) with multimedia software to create a training device. For example, major aircraft manufacturers have developed CAL programs to teach aircraft systems and maintenance procedures to their employees, reducing the amount of instructor time necessary to train aircrews and maintenance technicians on the new equipment. End users of the aircraft, such as the major airlines, can purchase the training materials with the aircraft in order to accomplish both initial and recurrent training of their personnel. Major advantages of CAL are that learners can progress at a rate which is comfortable for them and are often able to access the CAL at their own convenience.

Another benefit of CAL is an FAA test prep study guide, useful for preparation for the FAA knowledge tests. These programs typically allow the learners to select a test, complete the questions, and find out how they did on the test. The learner may then conduct a review of questions missed.

Some of the more advanced CAL applications allow learners to progress through a series of interactive segments where the presentation varies as a result of their responses. They can focus on the area they either need to study or want to study. For example, a maintenance learner who wants to find information on the refueling of a specific aircraft could use a CAL program to access the refueling section, and study the entire procedure. If the learner wishes to repeat a section or a portion of the section, it can be done at any time.

CAL programs can be used by the instructor as another type of study reference. Just as a learner can reread a section in a text, the learner may review portions of a CAL program. The instructor should continue to monitor and evaluate the progress of the learner as usual. This is necessary to be certain a learner is on track with the training syllabus. When using CAL, instructors may do more oneon-one instruction than in a normal classroom setting, since repetitive forms of teaching may be accomplished by computer. Remember, the computer has no way of knowing when a learner is having difficulty, and it will always be the responsibility of the instructor to provide monitoring and oversight of learner progress. [Figure 5-13]

Real interactivity with CAL means the learner is fully engaged with the instruction by doing something meaningful which makes the subject of study come alive. For example, the learner controls the pace of instruction, reviews previous material, jumps forward, and receives instant feedback. With advanced tracking features, CAL also can be used to test the learner’s achievement, compare the results with past performance, and indicate weak or strong areas. For most aviation training, the computer should be thought of as a valuable instructional aid, and CAL is a useful tool for aviation instructors. For example, in teaching aircraft maintenance, CAL programs produced by various aircraft manufacturers can be used to expose learners to equipment not normally found at a maintenance school. Another use of computers would allow learners to review procedures at their own pace while the instructor is involved in hands-on training with others. The major advantage of CAL is that it is interactive—the computer responds in different ways, depending on learner input. When using CAL, the instructor should remain actively involved with the learners by using close supervision, questions, examinations, quizzes, or guided discussions on the subject matter to constantly assess progress.

Figure 5-13. The instructor continually monitors learner performance when using CAL, as with all instructional aids.

Simulation, Role-Playing, and Video Gaming

Simulation (the appearance of real life), role-playing (playing a specific role in the context of a real-world situation), and video gaming have taken e-learning in new directions. [Figure 5-14] The popularity of simulation games that provide players with complex situations and opportunities to learn have drawn educators into the gaming field as they seek interactive educational games that help retain subject matter learning.

The advantages of simulation/role-playing games come as the learner obtains new information, develops skills, connects and manipulates information. A game gives the learner a stake in the outcome by putting them into the shoes of a character (role-playing) who needs to overcome a real-world scenario. Learning evolves as a result of the interactions with the game, and these games usually promote the development of critical thinking skills. Not every aviation learning objective can be delivered via this teaching method, but it should prove to be a useful tool in the instructor’s tool box as the number and content of educational games increase.

Figure 5-14. Flight simulator.

Cooperative or Group Learning Method

Cooperative or group learning organizes learners into small groups who can work together to maximize understanding. Research indicates that learners completing cooperative learning group tasks tend to have better test scores, higher self-esteem, improved social skills, and greater comprehension of the subjects they are studying. Perhaps the most significant characteristic of group learning is that it continually requires active participation in the learning process.

Conditions and Controls

In spite of its advantages, success with cooperative or group learning depends on conditions and controls. First of all, instructors need to begin planning early to determine what the group is expected to learn and to be able to do on their own. The group task may emphasize academic achievement, cognitive abilities, or physical skills, but the instructor should use clear and specific objectives to describe the knowledge and/or abilities the learners are to acquire and then demonstrate on their own.

The following conditions and controls are useful for cooperative learning:

⦁ Small, heterogeneous groups

⦁ Clear, complete instructions of what learners are to do, in what order, with what materials, and when appropriate—what learners are to do as evidence of their mastery of targeted content and skills ⦁ Learner perception of targeted objectives as their own, personal objectives

⦁ The opportunity for learner success

⦁ Learner access to and comprehension of required information

⦁ Sufficient time for learning

⦁ Individual accountability

⦁ Recognition and rewards for group success

⦁ Time after completion of group tasks for learners to systematically reflect upon how they worked together as

a team

In practice, collaborative, learner-led, instructor-led, or working group strategies are types of group learning. In these examples, the leader or the instructor serves as a coach or facilitator who interacts with the group, as necessary, to keep it on track or to encourage everyone in the group to participate.

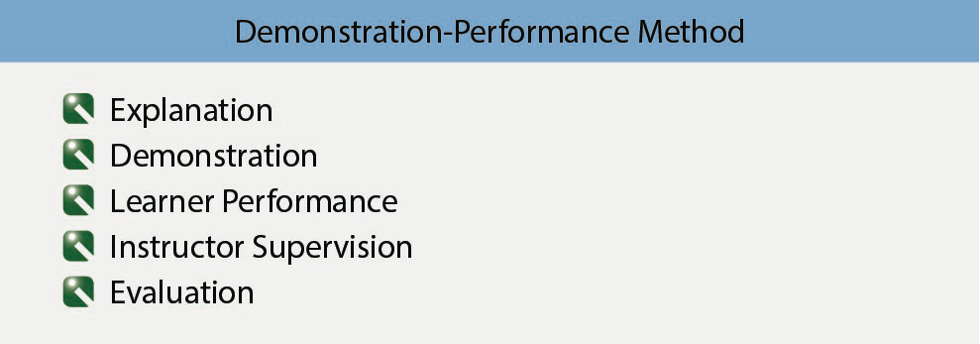

Demonstration-Performance Method

Best used for the mastery of mental or physical skills that require practice, the demonstration-performance method is based on the principle that people learn by doing. In this method, learners observe the skill and then try to reproduce it. It is well suited for the aircraft maintenance instructor who uses it in the shop to teach welding, and the flight instructor who uses it in teaching piloting skills.

Every instructor should recognize the importance of learner performance in the process. Early in demonstration and performance lesson, the instructor should identify the most important learning outcomes. Next, explain and demonstrate the steps involved in performing the skill being taught. Then, allow learners time to practice each step, so they can increase their ability to perform the skill.

The demonstration-performance method is divided into five phases: explanation, demonstration, learner performance, instructor supervision, and evaluation. [Figure 5-15]

Explanation Phase

Explanations need to be clear, pertinent to the objectives of the particular lesson to be presented, and based on the known experience and knowledge of the learners. In teaching a skill, the instructor conveys to the learners the precise actions they are to perform. In addition to the necessary steps, the instructor should describe the end result of these efforts. Before leaving this phase, the instructor should encourage learners to ask questions about any step of the procedure that they do not understand.

Figure 5-15. The demonstration-performance method of teaching has five essential phases.

Demonstration Phase

The instructor shows learners the actions necessary to perform a skill. Extraneous activity should be excluded from the demonstration so that learners clearly understand the desired actions. If the demonstration deviates from the explanation, this deviation should be immediately acknowledged and explained.

Learner Performance and Instruction Supervision Phases

While they involve separate actions, the learner’s performance of the physical or mental skills that and the instructor’s supervision occur at the same time.

The instructor needs to allot enough time for meaningful activity. Through doing, learners learn to follow correct procedures and to reach established standards. It is important that learners be given an opportunity to perform the skill as soon as possible after a demonstration. In flight training, the instructor may allow the learner to follow along on the controls during the demonstration of a maneuver. Immediately thereafter, the instructor should have the learner attempt to perform the maneuver, coaching as necessary. In the opening scenario, learners performed a task (weight and balance computation) as a group, and prior to terminating the performance phase, they were allowed to independently complete the task at least once with supervision and coaching as necessary.

Evaluation Phase

In this phase, the instructor judges learner performance. The learner displays whatever competence has been attained, and the instructor identifies how well the skill has been mastered. To test performance ability, the instructor requires learners to work independently throughout this phase and makes some comment about how each performed the skill relative to the way it was taught. From this measurement of learner achievement, the instructor determines the effectiveness of the instruction.

Drill and Practice Method

Drill and practice, based on Thorndike’s law of exercise discussed in Chapter 3, The Learning Process, predicts that connections are strengthened with practice. The human mind rarely retains, evaluates, and applies new concepts or practices after one exposure. Learners do not master welding during one shop period or perform crosswind landings during one instructional flight. They learn by practicing and applying what they have been told and shown. Every time practice occurs, learning continues. Effective use of drill and practice revolves around what skill is being developed. The instructor provides opportunities for learners to practice and while directing the process toward an objective.

Conclusion

A successful instructor needs to be various teaching methods. Although lecture and demonstration-performance methods usually work well, awareness of other methods and teaching tools such as guided discussion, cooperative learning, and computer-assisted learning better prepares an instructor for a wide variety of teaching situations.

Obviously, the aviation instructor is the key to effective teaching. The instructor’s tools are different teaching methods. Just as the technician uses some tools more than others, the instructor uses some methods more often than others. As is the case with the technician, there are times when a less used tool is the exact tool needed for a particular situation. The instructor’s success is determined to a large degree by the ability to organize material and to select and utilize a teaching method appropriate to a particular lesson.

Application of the Lesson

Application is the learner’s use of the presented material. If it is a classroom presentation, the learner may be asked to explain the new material. If it is a new flight maneuver, the learner may be asked to perform the maneuver just been demonstrated. In most instructional situations, the instructor’s explanation and demonstration activities alternate with learner performance efforts. Usually the instructor offers corrections and further demonstrations. This is necessary because each learner needs to perform the maneuver or operation the right way the first few times to establish a good habit. Faulty habits are difficult to correct and need to be addressed as soon as possible. Flight instructors should know about this issue since learners often practice without an instructor. Periodic review and assessment by the instructor is necessary to ensure that the learner has not acquired any bad habits, and learners should practice maneuvers on solo flights only after demonstrating reasonable competence.

As the learner becomes proficient with the fundamentals of flight and aircraft maneuvers or maintenance procedures, the instructor should increasingly emphasize ADM as a means of applying what has been previously learned. For example, the flight learner may be asked to plan for the arrival at a specific nontowered airport. The planning should take into consideration the wind conditions, arrival paths, communication procedures, available runways, recommended traffic patterns, and courses of action in the event the unexpected occurs. Upon arrival at the airport the learner makes decisions (with guidance and feedback as necessary) to safely enter and fly the traffic pattern.

Assessment of the Lesson

Before the end of the instructional period, the instructor should review what has been covered during the lesson and ask the learners to demonstrate how well the lesson objectives have been met. Review and assessment are integral parts of each classroom, or flight lesson. The instructor’s assessment may be informal and recorded only for the instructor’s own use in planning the next lesson, or it may be formal. Often, the assessment is formal and results recorded to certify the learner’s progress in the course. Assessment is explored in more detail in Chapter 6.

Instructional Aids and Training Technologies

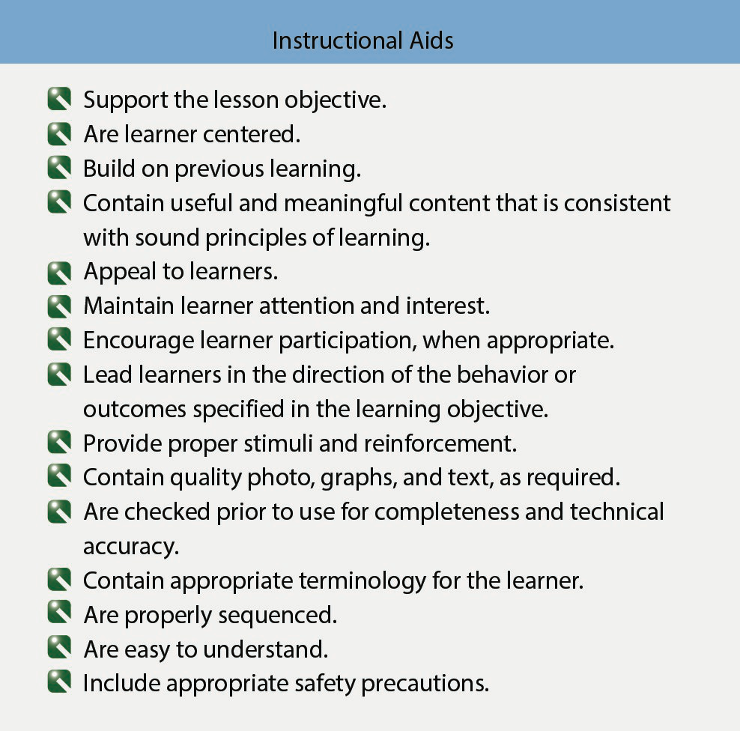

Instructional aids are devices that assist an instructor in the teaching-learning process. Instructional aids are not self-supporting; they support, supplement, or reinforce what is being taught. In contrast, training media are generally described as any physical means that communicates an instructional message to learners. For example, the instructor’s voice, printed text, video cassettes, interactive computer programs, part-task trainers, flight training devices, or flight simulators, and numerous other types of training devices are considered training media.

In school settings, instructors may be involved in the selection and preparation of instructional aids, but they often are already in place. An independent instructor may select or prepare instructional aids. Whatever the setting, instructors need to know how to use them effectively.

Instructional Aid Theory

There is general agreement about certain factors that seem pertinent to understanding the use of instructional aids.

⦁ Carefully selected charts, graphs, pictures, or other well-organized visual aids are examples of items that help the learner understand, as well as retain, essential information.

⦁ Ideally, instructional aids cover the key points and concepts.

⦁ The coverage should be straightforward and factual so it is easy for learners to remember and recall.

⦁ Generally, instructional aids that are relatively simple are best.

Reasons for Use of Instructional Aids

Properly used instructional aids help gain and hold the attention of learners. Audio or visual aids can be very useful in supporting a topic, and the combination of both audio and visual stimuli is particularly effective since the two most important senses are involved. One caution—the instructional aid should keep learner attention on the subject; it should not be a distracting gimmick.

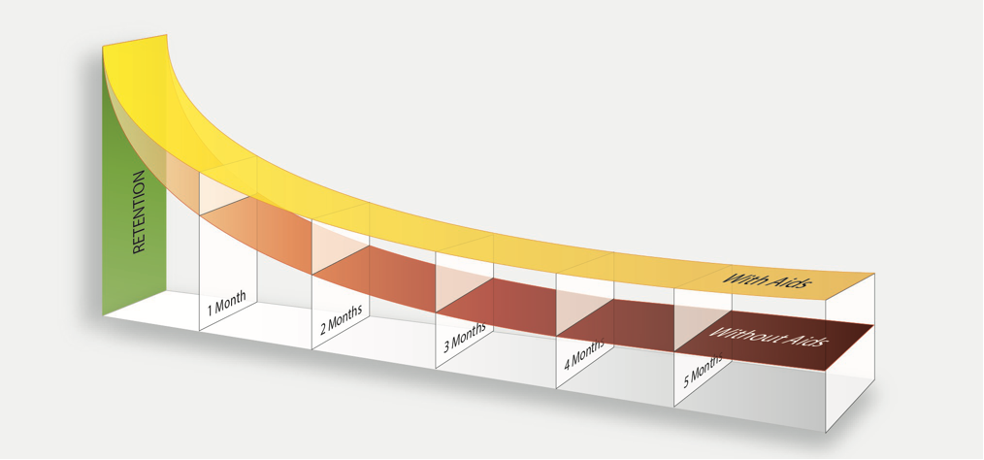

Clearly, a major goal of all instruction is for the learner to be able to retain as much knowledge of the subject as possible, especially the key points. Numerous studies have attempted to determine how well instructional aids serve this purpose. Indications from the studies vary greatly—from modest results, which show a 10 to 15 percent increase in retention, to more optimistic results in which retention is increased by as much as 80 percent. [Figure 5-16]

Figure 5-16. Studies generally agree that measurable improvement in learner retention of information occurs when instruction is supported by appropriate instructional aids.