Introduction

Aeronautical decision-making (ADM) is decision-making in a unique environment—aviation. It is a systematic approach to the mental process used by pilots to consistently determine the best course of action in response to a given set of circumstances. It is what a pilot intends to do based on the latest information he or she has.

The importance of learning and understanding effective ADM skills cannot be overemphasized. While progress is continually being made in the advancement of pilot training methods, aircraft equipment and systems, and services for pilots, accidents still occur. Despite all the changes in technology to improve flight safety, one factor remains the same: the human factor which leads to errors. It is estimated that approximately 80 percent of all aviation accidents are related to human factors and the vast majority of these accidents occur during landing (24.1 percent) and takeoff (23.4 percent).

ADM is a systematic approach to risk assessment and stress management. To understand ADM is to also understand how personal attitudes can influence decision-making and how those attitudes can be modified to enhance safety in the operation of a small UA. It is important to understand the factors that cause humans to make decisions and how the decision-making process not only works, but can be improved.

History of ADM

For over 25 years, the importance of good pilot judgment, or aeronautical decision-making (ADM), has been recognized as critical to the safe operation of aircraft, as well as accident avoidance. The airline industry, motivated by the need to reduce accidents caused by human factors, developed the first training programs based on improving ADM. Crew resource management (CRM) training for flight crews is focused on the effective use of all available resources: human resources, hardware, and information supporting ADM to facilitate crew cooperation and improve decision-making. The goal of all flight crews is good ADM and the use of CRM is one way to make good decisions.

Research in this area prompted the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to produce training directed at improving the decision-making of pilots and led to current FAA regulations that require that decision-making be taught as part of the pilot training curriculum. Aeronautical Decision Making and Risk Management are topics that the FAA is required to test an applicant about for the issuance of an sUAS certificate. ADM research, development, and testing culminated in 1987 with the publication of six manuals oriented to the decision-making needs of variously rated pilots. These manuals provided multifaceted materials designed to reduce the number of decision-related accidents. The effectiveness of these materials was validated in independent studies where student pilots received such training in conjunction with the standard flying curriculum. When tested, the pilots who had received ADM training made fewer inflight errors than those who had not received ADM training. The differences were statistically significant and ranged from about 10 to 50 percent fewer judgment errors. In the operational environment, an operator flying about 400,000 hours annually demonstrated a 54 percent reduction in accident rate after using these materials for recurrency training.

Contrary to popular opinion, good judgment can be taught. Tradition held that good judgment was a natural by-product of experience, but as pilots continued to log accident-free flight hours, a corresponding increase of good judgment was assumed. Building upon the foundation of conventional decision-making, ADM enhances the process to decrease the probability of human error and increase the probability of a safe flight. ADM provides a structured, systematic approach to analyzing changes that occur during a flight and how these changes might affect the safe outcome of a flight. The ADM process addresses all aspects of decision-making and identifies the steps involved in good decision making.

Steps for good decision-making are:

1. Identifying personal attitudes hazardous to safe flight.

2. Learning behavior modification techniques.

3. Learning how to recognize and cope with stress.

4. Developing risk assessment skills.

5. Using all resources.

6. Evaluating the effectiveness of one’s ADM skills.

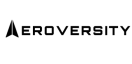

Risk Management

The goal of risk management is to proactively identify safety-related hazards and mitigate the associated risks. Risk management is an important component of ADM. When a pilot follows good decision-making practices, the inherent risk in a flight is reduced or even eliminated. The ability to make good decisions is based upon direct or indirect experience and education. The formal risk management decision-making process involves six steps as shown in Figure 10-1. Consider automotive seat belt use. In just two decades, seat belt use has become the norm, placing those who do not wear seat belts outside the norm, but this group may learn to wear a seat belt by either direct or indirect experience. For example, a driver learns through direct experience about the value of wearing a seat belt when he or she is involved in a car accident that leads to a personal injury. An indirect learning experience occurs when a loved one is injured during a car accident because he or she failed to wear a seat belt.

Figure 10-1. Risk management decision-making process.

As you work through the ADM cycle, it is important to remember the four fundamental principles of risk management.

- Accept no unnecessary risk. Flying is not possible without risk, but unnecessary risk comes without a corresponding return.

- Make risk decisions at the appropriate level. Risk decisions should be made by the person who can develop and implement risk controls.

- Accept risk when benefits outweigh dangers (costs).

- Integrate risk management into planning at all levels. Because risk is an unavoidable part of every flight, safety requires the use of appropriate and effective risk management not just in the preflight planning stage, but in all stages of the flight.

While poor decision-making in everyday life does not always lead to tragedy, the margin for error in aviation is thin. Since ADM enhances management of an aeronautical environment, all pilots should become familiar with and employ ADM.

Crew Resource Management (CRM) and Single-Pilot Resource Management

While CRM focuses on pilots operating in crew environments, many of the concepts apply to single pilot operations. Many CRM principles have been successfully applied to single-pilot aircraft and led to the development of Single-Pilot Resource Management (SRM). SRM is defined as the art and science of managing all the resources available to a single pilot (prior to and during flight) to ensure the successful outcome of the flight. SRM includes the concepts of ADM, risk management (RM), task management (TM), automation management (AM), controlled flight into terrain (CFIT) awareness, and situational awareness (SA). SRM training helps the pilot maintain situational awareness by managing the automation and associated aircraft control and navigation tasks. This enables the pilot to accurately assess and manage risk and make accurate and timely decisions.

SRM is all about helping pilots learn how to gather information, analyze it, and make decisions.

Hazard and Risk

Two defining elements of ADM are hazard and risk. Hazard is a real or perceived condition, event, or circumstance that a pilot encounters. When faced with a hazard, the pilot makes an assessment of that hazard based upon various factors. The pilot assigns a value to the potential impact of the hazard, which qualifies the pilot’s assessment of the hazard—risk.

Therefore, risk is an assessment of the single or cumulative hazard facing a pilot; however, different pilots see hazards differently.

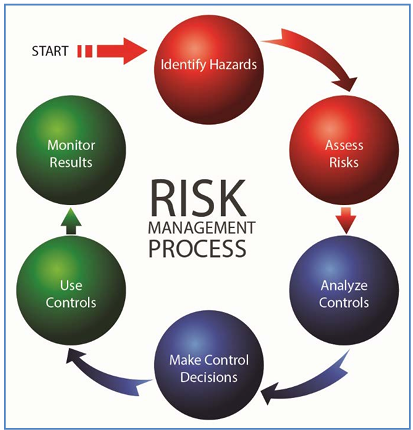

Hazardous Attitudes and Antidotes

Being fit to fly depends on more than just a pilot’s physical condition and recent experience. For example, attitude affects the quality of decisions. Attitude is a motivational predisposition to respond to people, situations, or events in a given manner. Studies have identified five hazardous attitudes that can interfere with the ability to make sound decisions and exercise authority properly: anti-authority, impulsivity, invulnerability, macho, and resignation. [Figure 10-2]

Hazardous attitudes contribute to poor pilot judgment but can be effectively counteracted by redirecting the hazardous attitude so that correct action can be taken. Recognition of hazardous thoughts is the first step toward neutralizing them. After recognizing a thought as hazardous, the pilot should label it as hazardous, then state the corresponding antidote. Antidotes should be memorized for each of the hazardous attitudes so they automatically come to mind when needed.

Figure 10-2. The five hazardous attitudes identified through past and contemporary study.

Risk

During each flight, the single pilot makes many decisions under hazardous conditions. To fly safely, the pilot needs to assess the degree of risk and determine the best course of action to mitigate the risk.

Assessing Risk

For the single pilot, assessing risk is not as simple as it sounds. For example, the pilot acts as his or her own quality control in making decisions. If a fatigued pilot who has flown 16 hours is asked if he or she is too tired to continue flying, the answer may be “no.” Most pilots are goal oriented and when asked to accept a flight, there is a tendency to deny personal limitations while adding weight to issues not germane to the mission. For example, pilots of helicopter emergency services (EMS) have been known (more than other groups) to make flight decisions that add significant weight to the patient’s welfare. These pilots add weight to intangible factors (the patient in this case) and fail to appropriately quantify actual hazards, such as fatigue or weather, when making flight decisions. The single pilot who has no other crew member for consultation must wrestle with the intangible factors that draw one into a hazardous position. Therefore, he or she has a greater vulnerability than a full crew.

Mitigating Risk

Risk assessment is only part of the equation.

One of the best ways single pilots can mitigate risk is to use the IMSAFE checklist to determine physical and mental readiness for flying:

1. Illness—Am I sick? Illness is an obvious pilot risk.

2. Medication—Am I taking any medicines that might affect my judgment or make me drowsy? 3. Stress—Am I under psychological pressure from the job? Do I have money, health, or family problems? Stress causes concentration and performance problems. While the regulations list medical conditions that require grounding, stress is not among them. The pilot should consider the effects of stress on performance.

4. Alcohol—Have I been drinking within 8 hours? Within 24 hours? As little as one ounce of liquor, one bottle of beer, or four ounces of wine can impair flying skills. Alcohol also renders a pilot more susceptible to disorientation and hypoxia.

5. Fatigue—Am I tired and not adequately rested? Fatigue continues to be one of the most insidious hazards to flight safety, as it may not be apparent to a pilot until serious errors are made.

6. Emotion—Am I emotionally upset?

The PAVE Checklist

Another way to mitigate risk is to perceive hazards. By incorporating the PAVE checklist into preflight planning, the pilot divides the risks of flight into four categories: Pilot-in-command (PIC), Aircraft, enVironment, and External pressures (PAVE) which form part of a pilot’s decision-making process.

With the PAVE checklist, pilots have a simple way to remember each category to examine for risk prior to each flight.

Once a pilot identifies the risks of a flight, he or she needs to decide whether the risk, or combination of risks, can be managed safely and successfully. If not, make the decision to cancel the flight. If the pilot decides to continue with the flight, he or she should develop strategies to mitigate the risks. One way a pilot can control the risks is to set personal minimums for items in each risk category. These are limits unique to that individual pilot’s current level of experience and proficiency.

P = Pilot-in-Command (PIC)

The pilot is one of the risk factors in a flight. The pilot must ask, “Am I ready for this flight?” in terms of experience, recency, currency, physical, and emotional condition. The IMSAFE checklist provides the answers.

A = Aircraft

What limitations will the aircraft impose upon the trip? Ask the following questions: • Is this the right aircraft for the flight?

• Am I familiar with and current in this aircraft?

• Can this aircraft carry the planned load?

V = EnVironment

Weather

Weather is a major environmental consideration. Earlier it was suggested pilots set their own personal minimums, especially when it comes to weather. As pilots evaluate the weather for a particular flight, they should consider the following:

• What is the current ceiling and visibility?

• Consider the possibility that the weather may be different than forecast.

• Are there any thunderstorms present or forecast?

• If there are clouds, is there any icing, current or forecast? What is the temperature/dew point spread and the current temperature at altitude?

Terrain

Evaluation of terrain is another important component of analyzing the flight environment.

Airspace

Check the airspace and any temporary flight restriction (TFRs).

E = External Pressures

External pressures are influences external to the flight that create a sense of pressure to complete a flight—often at the expense of safety. Factors that can be external pressures include the following:

• The desire to demonstrate pilot qualifications

• The desire to impress someone (Probably the two most dangerous words in aviation are “Watch this!”)

• The pilot’s general goal-completion orientation

• Emotional pressure associated with acknowledging that skill and experience levels may be lower than a pilot would like them to be. Pride can be a powerful external factor!

Managing External Pressures

Management of external pressure is the single most important key to risk management because it is the one risk factor category that can cause a pilot to ignore all the other risk factors.

The use of personal standard operating procedures (SOPs) is one way to manage external pressures. The goal is to supply a release for the external pressures of a flight.

Human Factors

Why are human conditions, such as fatigue, complacency and stress, so important in aviation? These conditions, along with many others, are called human factors. Human factors directly cause or contribute to many aviation accidents and have been documented as a primary contributor to more than 70 percent of aircraft accidents.

Typically, human factor incidents/accidents are associated with flight operations but recently have also become a major concern in aviation maintenance and air traffic management as well. Over the past several years, the FAA has made the study and research of human factors a top priority by working closely with engineers, pilots, mechanics, and ATC to apply the latest knowledge about human factors in an effort to help operators and maintainers improve safety and efficiency in their daily operations.

Human factors science, or human factors technologies, is a multidisciplinary field incorporating contributions from psychology, engineering, industrial design, statistics, operations research, and anthropometry. It is a term that covers the science of understanding the properties of human capability, the application of this understanding to the design, development and deployment of systems and services, and the art of ensuring successful application of human factor principles into all aspects of aviation to include pilots, ATC, and aviation maintenance. Human factors is often considered synonymous with CRM or maintenance resource management (MRM) but is really much broader in both its knowledge base and scope. Human factors involves gathering research specific to certain situations (i.e., flight, maintenance, stress levels, knowledge) about human abilities, limitations, and other characteristics and applying it to tool design, machines, systems, tasks, jobs, and environments to produce safe, comfortable, and effective human use. The entire aviation community benefits greatly from human factors research and development as it helps better understand how humans can most safely and efficiently perform their jobs and improve the tools and systems in which they interact.

The Decision-Making Process

An understanding of the decision-making process provides the pilot with a foundation for developing ADM and SRM skills. While some situations, such as engine failure, require an immediate pilot response using established procedures, there is usually time during a flight to analyze any changes that occur, gather information, and assess risks before reaching a decision.

Risk management and risk intervention is much more than the simple definitions of the terms might suggest. Risk management and risk intervention are decision-making processes designed to systematically identify hazards, assess the degree of risk, and determine the best course of action. These processes involve the identification of hazards, followed by assessments of the risks, analysis of the controls, making control decisions, using the controls, and monitoring the results.

The steps leading to this decision constitute a decision-making process. Three models of a structured framework for problem-solving and decision-making are the 5P, the 3P using PAVE, CARE and TEAM, and the DECIDE models. They provide assistance in organizing the decision process. All these models have been identified as helpful to the single pilot in organizing critical decisions.

Single-Pilot Resource Management (SRM)

Single-Pilot Resource Management (SRM) is about how to gather information, analyze it, and make decisions. Learning how to identify problems, analyze the information, and make informed and timely decisions is not as straightforward as the training involved in learning specific maneuvers. Learning how to judge a situation and “how to think” in the endless variety of situations encountered while flying out in the “real world” is more difficult.

There is no one right answer in ADM, rather each pilot is expected to analyze each situation in light of experience level, personal minimums, and current physical and mental readiness level, and make his or her own decision.

Perceive, Process, Perform (3P) Model

The Perceive, Process, Perform (3P) model for ADM offers a simple, practical, and systematic approach that can be used during all phases of flight. To use it, the pilot will:

- Perceive the given set of circumstances for a flight

- Process by evaluating their impact on flight safety

- Perform by implementing the best course of action

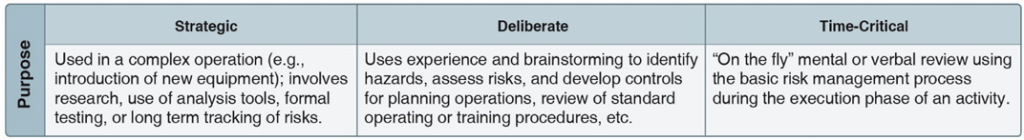

Use the Perceive, Process, Perform, and Evaluate method as a continuous model for every aeronautical decision that you make. Although human beings will inevitably make mistakes, anything that you can do to recognize and minimize potential threats to your safety will make you a better pilot. Depending upon the nature of the activity and the time available, risk management processing can take place in any of three timeframes. [Figure 10-3] Most flight training activities take place in the “time-critical” timeframe for risk management. The six steps of risk management can be combined into an easy-to-remember 3P model for practical risk management: Perceive, Process, Perform with the PAVE, CARE and TEAM checklists. Pilots can help perceive hazards by using the PAVE checklist of: Pilot, Aircraft, enVironment, and External pressures. They can process hazards by using the CARE checklist of: Consequences, Alternatives, Reality, External factors. Finally, pilots can perform risk management by using the TEAM choice list of: Transfer, Eliminate, Accept, or Mitigate.

Figure 10-3. Risk management processing can take place in any of three timeframes.

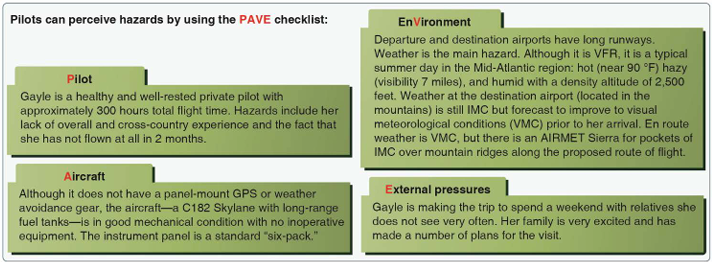

PAVE Checklist: Identify Hazards and Personal Minimums

In the first step, the goal is to develop situational awareness by perceiving hazards, which are present events, objects, or circumstances that could contribute to an undesired future event. In this step, the pilot will systematically identify and list hazards associated with all aspects of the flight: Pilot, Aircraft, enVironment, and External pressures, which makes up the PAVE checklist. [Figure 10-4] All four elements combine and interact to create a unique situation for any flight. Pay special attention to the pilot-aircraft combination, and consider whether the combined “pilot-aircraft team” is capable of the mission you want to fly. For example, you may be a very experienced and proficient pilot, but your weather flying ability is still limited if you are flying an unfamiliar aircraft. On the other hand, you may have a new technically advanced aircraft that you have flown for a considerable amount of time.

Figure 10-4. A real-world example of how the 3P model guides decisions on a cross-country trip using the PAVE checklist.

Decision-Making in a Dynamic Environment

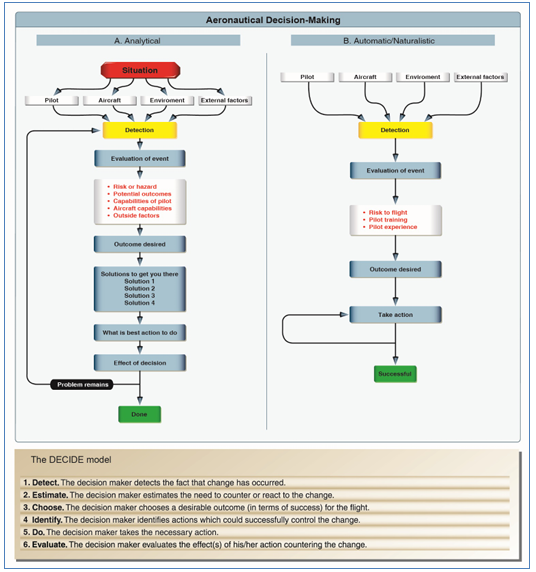

A solid approach to decision-making is through the use of analytical models, such as the 5 Ps, 3P, and DECIDE. Good decisions result when pilots gather all available information, review it, analyze the options, rate the options, select a course of action, and evaluate that course of action for correctness.

In some situations, there is not always time to make decisions based on analytical decision-making skills. A good example is a quarterback whose actions are based upon a highly fluid and changing situation. He intends to execute a plan, but new circumstances dictate decision-making on the fly. This type of decision-making is called automatic decision-making or naturalized decision-making. [Figure 10-5B]

Figure 10-5. The DECIDE model has been recognized worldwide. Its application is illustrated in column A while automatic/naturalistic decision-making is shown in column B.

Automatic Decision-Making

For the past several decades, research into how people actually make decisions has revealed that when pressed for time, experts faced with a task loaded with uncertainty first assess whether the situation strikes them as familiar. Rather than comparing the pros and cons of different approaches, they quickly imagine how one or a few possible courses of action in such situations will play out.

Experts take the first workable option they can find. While it may not be the best of all possible choices, it often yields remarkably good results.

The terms “naturalistic” and “automatic decision-making” have been coined to describe this type of decision-making. The ability to make automatic decisions holds true for a range of experts from firefighters to chess players. It appears the expert’s ability hinges on the recognition of patterns and consistencies that clarify options in complex situations. Experts appear to make provisional sense of a situation, without actually reaching a decision, by launching experience-based actions that in turn trigger creative revisions.

This is a reflexive type of decision-making anchored in training and experience and is most often used in times of emergencies when there is no time to practice analytical decision-making. Naturalistic or automatic decision-making improves with training and experience, and a pilot will find himself or herself using a combination of decision-making tools that correlate with individual experience and training.

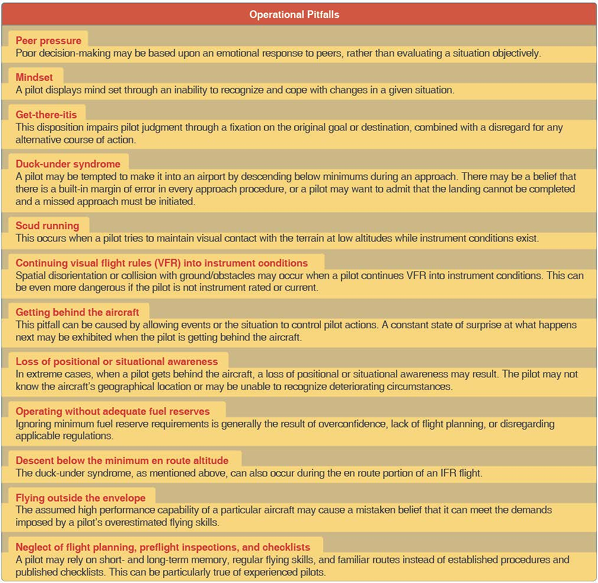

Operational Pitfalls

Although more experienced pilots are likely to make more automatic decisions, there are tendencies or operational pitfalls that come with the development of pilot experience. These are classic behavioral traps into which pilots have been known to fall. More experienced pilots, as a rule, try to complete a flight as planned. The desire to meet these goals can have an adverse effect on safety and contribute to an unrealistic assessment of piloting skills. These dangerous tendencies or behavior patterns, which must be identified and eliminated, include the operational pitfalls shown in Figure 10-6.

Figure 10-6. Typical operational pitfalls requiring pilot awareness.

Stress Management

Everyone is stressed to some degree almost all of the time. A certain amount of stress is good since it keeps a person alert and prevents complacency. Effects of stress are cumulative and, if the pilot does not cope with them in an appropriate way, they can eventually add up to an intolerable burden. Performance generally increases with the onset of stress, peaks, and then begins to fall off rapidly as stress levels exceed a person’s ability to cope. The ability to make effective decisions during flight can be impaired by stress. There are two categories of stress—acute and chronic. These are both explained in Chapter 9, “Physiological Factors (Including Drugs and Alcohol) Affecting Pilot Performance,” of this study guide.

There are several techniques to help manage the accumulation of life stresses and prevent stress overload. For example, to help reduce stress levels, set aside time for relaxation each day or maintain a program of physical fitness. To prevent stress overload, learn to manage time more effectively to avoid pressures imposed by getting behind schedule and not meeting deadlines.

Use of Resources

To make informed decisions during flight operations, a pilot must also become aware of the available resources. Since useful tools and sources of information may not always be readily apparent, learning to recognize these resources is an essential part of ADM training. Resources must not only be identified, but a pilot must also develop the skills to evaluate whether there is time to use a particular resource and the impact its use will have upon the safety of flight.

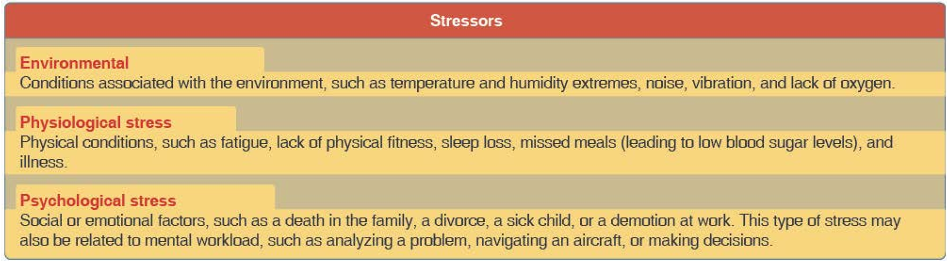

Figure 10-7. System stressors. Environmental, physiological, and psychological stress are factors that affect decision-making skills. These stressors have a profound impact especially during periods of high workload.

Situational Awareness

Situational awareness is the accurate perception and understanding of all the factors and conditions within the five fundamental risk elements (flight, pilot, aircraft, environment, and type of operation that comprise any given aviation situation) that affect safety before, during, and after the flight.

Maintaining situational awareness requires an understanding of the relative significance of all flight related factors and their future impact on the flight. When a pilot understands what is going on and has an overview of the total operation, he or she is not fixated on one perceived significant factor. Not only is it important for a pilot to know the aircraft’s geographical location, it is also important he or she understand what is happening.

Obstacles to Maintaining Situational Awareness

Fatigue, stress, and work overload can cause a pilot to fixate on a single perceived important item and reduce an overall situational awareness of the flight. A contributing factor in many accidents is a distraction that diverts the pilot’s attention from monitoring the aircraft.

Workload Management

Effective workload management ensures essential operations are accomplished by planning, prioritizing, and sequencing tasks to avoid work overload. As experience is gained, a pilot learns to recognize future workload requirements and can prepare for high workload periods during times of low workload.

In addition, a pilot should listen to ATIS, Automated Surface Observing System (ASOS), or Automated Weather Observing System (AWOS), if available, and then monitor the tower frequency or Common Traffic Advisory Frequency (CTAF) to get a good idea of what traffic conditions to expect.

Recognizing a work overload situation is also an important component of managing workload. The first effect of high workload is that the pilot may be working harder but accomplishing less. As workload increases, attention cannot be devoted to several tasks at one time, and the pilot may begin to focus on one item. When a pilot becomes task saturated, there is no awareness of input from various sources, so decisions may be made on incomplete information and the possibility of error increases.

When a work overload situation exists, a pilot needs to stop, think, slow down, and prioritize. It is important to understand how to decrease workload.