Introduction

Risk mitigation reduces the likelihood or predicted severity of potential effects of hazards. As discussed in Chapter 4, Assessing Risk, high (red) and serious (yellow) risks should be mitigated. High risks the pilot cannot mitigate should lead to a no-go decision. Departing with serious risks is also an abnormal situation that calls for additional mitigation. The risk mitigation process may start days or weeks before a flight and depends on the complexity of the plan.

Air carrier, charter, and fractional operations conducted under 14 CFR parts 121, 135, and 91 Subpart K normally preclude operations in the serious and high-risk categories. Corporate turbojet operators also typically adhere to this standard. In addition to regulatory requirements, these operators utilize concepts, procedures, and tools such as safety management systems (SMS) to ensure risks are identified, assessed, and managed appropriately. General aviation pilots can manage risk in a professional manner as well. Risks should be managed such that they are mitigated to medium (green) levels or lower.

Risk mitigation may also allow a pilot to undertake or complete a flight that would otherwise be subject to unacceptable risks. Conversely, the pilot should not depart if the same process reveals safe flight is not possible under the given conditions.

If having a doubt about risk mitigation, a pilot should consider the value of mitigation against the potential cost of property damage and loss of life. A saying goes, safety costs a lot less than an accident. In fact, risk mitigation makes long-term economic sense.

Preflight Risk Mitigation Strategies

Pilots choose from a variety of strategies to mitigate risks, and different strategies may apply to different hazards. Nevertheless, there are a few general strategies that are effective for each area on the PAVE checklist. Pilot, aircraft, and external pressure risks respond well to early, direct action. On the other hand, the scope of many environmental hazards often favors avoidance as a mitigation strategy.

Mitigating Pilot Risks

Personal minimums that account for pilot experience and proficiency mitigate some risks. Pilots flying unfamiliar aircraft may need to raise their personal minimums for that aircraft. When training, pilots can take advantage of scenarios that include risk management in addition to pilot skill elements. Self-evaluation after a flight may alert a pilot of the need for additional training, which may also decrease future risk. If there is any doubt concerning the outcome of a flight, the pilot should consider hiring an instructor or a mentor pilot and making the trip a learning experience.

Use of and careful consideration of the IMSAFE checklist (illness, medication, stress, alcohol, fatigue, emotion) reduces aeromedical risk.

Mitigating Aircraft Risks

Factoring performance data to create safety margins mitigates some risks. Using an aircraft with redundant systems or an aircraft with automation that reduces pilot workload also lowers accident risk. Additionally, addressing discrepancies and conducting proper maintenance can increase reliability and reduce risk. Thorough preflight and postflight inspections also mitigate aircraft risks.

Carrying enough fuel with a sufficient reserve reduces the likelihood of a low-fuel emergency or a forced landing. On some flights, planning for a fuel stop reduces that risk.

If the pilot has a choice, the selection of aircraft may reduce risk. The decision may consider the aircraft performance, the number of engines, known icing capability, and avionics or automation available.

Mitigating Environmental Risks

Flight in the proximity of some environmental hazards may lead to serious or catastrophic accidents. Avoidance strategies reduce the risk by lowering the accident likelihood. This requires pilots to plan, exercise patience, remain flexible, and be creative.

Circumnavigate the Hazard

For some hazards, such as convective activity and very high terrain, a possible mitigation may be a plan to circumnavigate the hazard.

Go Above or Below the Hazard

Sometimes a plan to fly at a different altitude reduces accident likelihood. Pilots can plan for altitudes that keep the aircraft above or below icing conditions. Many instrument pilots who operate aircraft that are not approved for flight in known icing conditions apply personal minimums to avoid conditions below certain temperatures or where the freezing level is at or below the minimum en-route altitude.

Change Departure Time or Date

Advancing or delaying a departure may reduce risk likelihood. For example, on a day when a line of afternoon thunderstorms is forecast, a pilot could plan for an early morning departure or wait until the thunderstorms dissipate and depart late in the afternoon. For some meteorological hazards, such as an incoming low-pressure system, the pilot might choose to depart the day before originally planned.

Cancel the Flight

Canceling a flight is necessary if the pilot cannot mitigate risk sufficiently by other means. The cancellation option is easier if another means of transportation is available or if long-term rescheduling is an option.

Mitigating External Pressure Risks

External pressures can be either subtle or overt. Because it may involve passengers or others waiting for the arrival, it is best to inform them of the need for flexibility.

Local Versus Transportation Flights

A local pleasure flight can still be subject to external pressures, but it is easier to cancel than a scheduled flight related to transportation to an event. When planning a local flight with friends, for example, the pilot can reduce external pressures by telling them in advance that the flight could be canceled at the last minute due to weather or other reasons. For an IFR transportation flight, persons meeting the flight can use an application to know if the flight will arrive as planned. For a VFR flight anyone meeting the flight may wait at home and get notified after the flight arrives.

Personal Versus Business Flights

Pilots who fly business associates may feel significant external pressures. The pilot should manage passenger expectations and may plan for alternative travel options as a means to reduce risk.

Case Study

Note: Refer to the case study supporting data in Chapter 3, Identifying Hazards and Associated Risks, and the risk assessment matrix in Chapter 4, Assessing Risk, to continue the risk mitigation phase of the case study.

Risk Mitigation Analysis

Tricia diligently identified the hazards and assessed the risks of her proposed flight from Durango, CO to Santa Rosa, CA. She should now mitigate the high and serious risks that she identified during the assessment phase. She identified four high and five serious risks that she should attempt to mitigate by reducing risk likelihood, severity, or both.

Tricia starts by reconsidering the overall plan for this flight. She rules out making a non-stop flight because carrying the Smiths and their baggage would require a reduced fuel load, which in this case is a serious (yellow) risk. In addition, the direct route could lead to encounters with thunderstorms, icing conditions, areas of low ceilings, and high terrain. Furthermore, she realizes they should leave Monday morning, rather than Tuesday, because of the incoming front and low-pressure area. She also notes that there may be an issue with fog and low ceilings at Santa Rosa due to the coastal marine layer. This may dissipate by noon, but it is not yet possible to predict.

Tricia starts by calculating the allowable fuel load. With an empty weight of 1,903 pounds and a maximum allowable gross weight of 2,740 pounds, the useful load works out to 837 pounds. Tricia weighs 130 pounds, the Smiths together weigh 340 pounds. Together Tricia and the Smiths have 120 pounds of baggage. Tricia also has an electronic flight bag (EFB) and pilot gear totaling seven pounds. This leaves 240 pounds for fuel, which is 40 gallons. The airplane currently has 25 gallons on board.

There is a serious (yellow) hazard if making a gross weight takeoff from the Animas Air Park (00C). She decides to ask the Smiths to take a taxi to the Durango – La Plata County Airport (KDRO), which is about a ten-mile ride for them and a 7-nautical mile flight for her. It has a 9,200-foot runway. She can add 18 gallons of fuel before the short flight to Durango – La Plata County Airport, and can depart from there at gross weight, which includes 40 gallons of fuel. She plans to make one additional fuel stop.

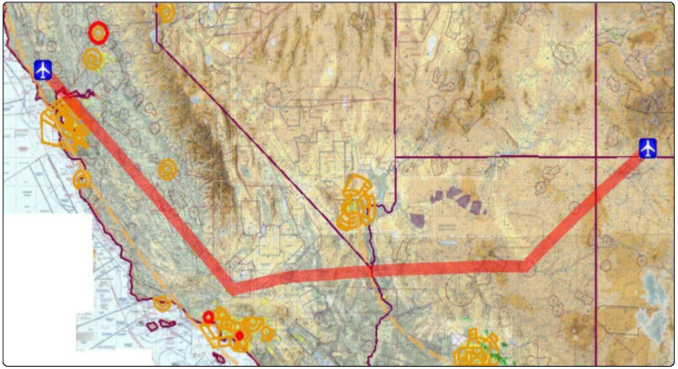

After a thorough analysis and weather briefing, she elects to fly a southern route to avoid hazardous weather. She plans to refuel at the Barstow-Daggett, CA airport (KDAG). The 490 NM route from Durango – La Plata County Airport uses the Winslow, AZ (INW) VOR as a waypoint and should take 3 hours and 15 minutes. She will have 4 hours and 30 minutes endurance. From there, she will fly to Santa Rosa using the Palmdale, CA (PMD) VOR as a waypoint. This route is 390 NM and should take 2 hours 45 minutes with a 4 hour and 30 minute endurance. [Figure 5-1]

Figure 5-1. Modified route.

The total distance along this route is 880 NM, versus the straight-line distance of 711 NM. The additional 169 NM adds about 1 hour and 15 minutes to the total flight time.

She mitigated the aircraft and environmental risks using this plan. She should also deal with the external pressure risks associated with leaving a day early, given the need for the Smiths to forgo the Monday festivities in Durango. An early departure also reduces the external pressures associated with making the Tuesday afternoon meetings on time. Tricia needs to explain the risk analysis to the Smiths and show them why a Monday departure is necessary.

She has concerns related to her instrument proficiency. To compensate, she decides to add 500 feet to her personal minimums for an instrument approach into Santa Rosa. This might require landing at a suitable alternate airport. With the predicted fuel load, she calculates that Sacramento Executive Airport (KSAC), 62 NM from KSTS and well inland, would be a good alternate.

She also considers pilot aeromedical risks. She will consume no alcohol, have an early dinner, and go to bed early. She also increases her intake of water. These actions should help avoid dehydration.

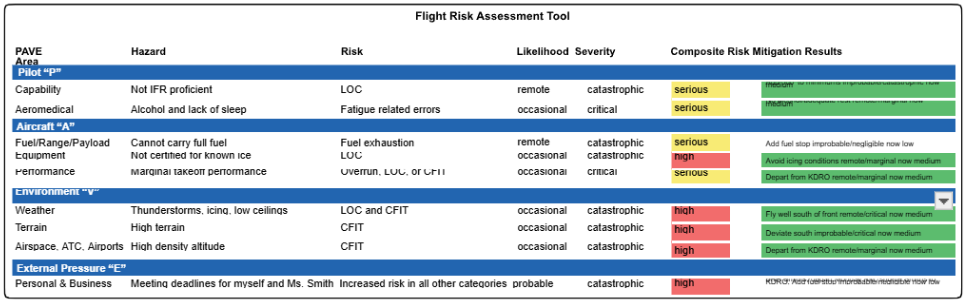

Having addressed all the previously identified risks, she completes the FRAT for the proposed trip, listing all of her mitigations. The completed FRAT in Figure 5-2 shows all the risks mitigated to medium or low levels. For illustrative purposes, the recalculated risk levels are shown on one sheet showing the before and after. When the conditions change significantly, such as for rescheduling or a change of aircraft, the pilot would normally redo the risk analysis using a fresh worksheet.

Figure 5-2. Case study FRAT with risks mitigated.

Of the nine risks assessed, she originally assessed four as high (red) and five as serious (yellow). According to her analysis and mitigations, the risk for the current plan has seven medium (green) and two low (white) risks.

Tricia meets with the Smiths. They agree with the early departure from Durango and the other mitigations. Matt Smith makes a few phone calls and returns with word that all of Monday’s festivities will go forward, but without the Smiths in attendance.

This risk mitigations used for the flight include the following:

- Adding a safety margin to personal minimums for instrument approaches;

- Abstaining from alcohol consumption, eating properly, and getting sufficient sleep;

- Reducing the departure fuel load and adding a fuel stop;

- Rescheduling to depart a day early;

- Departing with passengers from the Durango – La Plata County Airport, rather than from Animas Air Park; and

- Flying along a more southerly route to avoid weather hazards.

While on the ground in Daggett, CA for the planned fuel stop, Tricia checks the weather, which shows that the fog and low ceilings are persisting at Santa Rosa. She understands the potential consequences of slightly elevated risk if making an ILS approach with a 200- to 300-foot ceiling, and confirms her risk analysis remains valid by noting that her alternate, Sacramento Executive Airport, is reporting clear skies as forecast. She prepares her EFB for the possible diversion to Sacramento and reviews the airport information. This preparation alleviates the stress she may feel about diverting. She relieves external pressures by discussing a potential diversion with the Smiths, who indicate they will accept whatever decision she makes.

Within an hour after departure, the fog at Santa Rosa has lifted, and she executes a routine landing.

Several days later, Tricia receives a complementary note from the Smiths praising her consideration for safety.

Balanced Approach to Risk Management

The hypothetical case study used in Chapters 3 through 5 represents a moderately complex scenario covering the flight of a general aviation aircraft on a transportation flight.

It is appropriate to conduct a full risk management process for any flight, including the use of a FRAT. However, for less complex flights, such as a flight in the vicinity of the airport on a sunny day with no wind, the completion of a FRAT may not be necessary.

To enhance risk management accuracy and skill, consider the following steps:

- Take risk management and SRM courses.

- Obtain risk management training from a flight or ground instructor.

- Use a formal risk management process to reduce risk on all complex flights.

- If not using a FRAT, continue to use the PAVE checklist to identify hazards and assess and mitigate the associated risks.

Chapter Summary

Risk mitigation identifies hazards and reduces the likelihood or potential severity of associated risks. It may allow a pilot to undertake a flight that would otherwise generate unacceptable risk. In other cases, the risk mitigation process may identify high and serious risks that cannot be mitigated, which may require rescheduling, cancellation, or alternate transportation. A FRAT can enhance any risk mitigation analysis, but may not be required for simpler flights, provided the pilot has sufficient risk management skill. A brief FAA Safety Team (FAASTeam) video on risk-based decision-making summarizes many concepts discussed in this chapter.