Introduction

Radio communications are an important aspect for the safe operation of aircraft in the NAS. It is through radio communications that pilots give and receive information before, during and at the conclusion of a flight. This information aids in the flow of aircraft in highly complex airspace areas as well as in less populated areas. Pilots can also send and receive important safety of flight issues such as unexpected weather conditions, and inflight emergencies. Although small UA pilots are not expected to communicate over radio frequencies, it is important for the UA pilot to understand “aviation language” and the different conversations they will encounter if the UA pilot is using a radio to aid them in situational awareness when operating in the NAS. Although much of the information provided here is geared toward manned aircraft pilots, the UA pilot needs to understand the unique way information is exchanged in the NAS.

Understanding Proper Radio Procedures

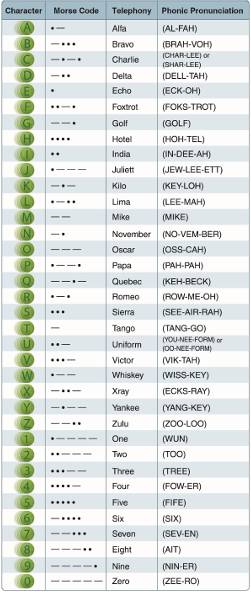

Understanding proper radio phraseology and procedures contribute to a pilot’s ability to operate safely and efficiently in the airspace system. A review of the Pilot/Controller Glossary contained in the AIM assists a pilot in understanding standard radio terminology. The AIM also contains many examples of radio communications. ICAO has adopted a phonetic alphabet that should be used in radio communications. When communicating with ATC, pilots should use this alphabet to identify their aircraft. [Figure 7-1]

Traffic Advisory Practices at Airports without Operating Control Towers

Airport Operations without Operating Control Tower

There is no substitute for alertness while in the vicinity of an airport. It is essential that pilots be alert and look for other traffic a when operating at an airport without an operating control tower. This is of particular importance since other aircraft may not have communication capability or, in some cases, pilots may not communicate their presence or intentions when operating into or out of such airports. To achieve the greatest degree of safety, it is essential that all radio equipped aircraft transmit/receive on a common frequency and small UA pilots monitor other aircraft identified for the purpose of airport advisories.

Figure 7-1. Phonetic Alphabet.

An airport may have a full or part-time tower or flight service station (FSS) located on the airport, a full or part-time universal communications (UNICOM) station or no aeronautical station at all. There are three ways for pilots to communicate their intention and obtain airport/traffic information when operating at an airport that does not have an operating tower—by communicating with an FSS, a UNICOM operator, or by making a self-announce broadcast.

Many airports are now providing completely automated weather, radio check capability and airport advisory information on an automated UNICOM system. These systems offer a variety of features, typically selectable by microphone clicks, on the UNICOM frequency. Availability of the automated UNICOM will be published in the Airport/Facility Directory and approach charts.

Understanding Communication on a Common Frequency

The key to communications at an airport without an operating control tower is selection of the correct common frequency. The acronym CTAF, which stands for Common Traffic Advisory Frequency, is synonymous with this program. A CTAF is a frequency designated for the purpose of carrying out airport advisory practices while operating to or from an airport without an operating control tower. The CTAF may be a UNICOM, MULTICOM, FSS, or tower frequency and is identified in appropriate aeronautical publications.

Communication/Broadcast Procedures

A MULTICOM frequency of 122.9 will be used at an airport that is non-towered and does not have a FSS or UNICOM.

Recommended Traffic Advisory Practices

Although a remote pilot-in-command is not required to communicate with manned aircraft when in the vicinity of a non-towered airport, safety in the National Airspace System requires that remote pilots are familiar with traffic patterns, radio procedures, and radio phraseology.

When a remote pilot plans to operate close to a non-towered airport, the first step in radio procedures is to identify the appropriate frequencies. Most non-towered airports will have a UNICOM frequency, which is usually 122.8; however, you should always check the Cart Supplements U.S. or sectional chart for the correct frequency. This frequency can vary when there are a large number of non-towered airports in the area. For non-towered airports that do not have a UNICOM or any other frequency listed, the MULTICOM frequency of 122.9 will be used. These frequencies can be found on a sectional chart by the airport or in the Chart Supplements publication from the FAA.

When a manned aircraft is inbound to a non-towered airport, the standard operating practice is for the pilot to “broadcast in the blind” when 10 miles from the airport. This initial radio call will also include the position the aircraft is in relation to north, south, east or west from the airport. For example:

Town and Country traffic, Cessna 123 Bravo Foxtrot is 10 miles south inbound for landing, Town and Country traffic.

When a manned aircraft is broadcasting at a non-towed airport, the aircraft should use the name of the airport of intended landing at the beginning of the broadcast, and again at the end of the broadcast. The reason for stating the name twice is to allow others who are on the frequency to confirm where the aircraft is going. The next broadcast that the manned aircraft should make is:

Town and Country traffic, Cessna 123 Bravo Foxtrot, is entering the pattern, mid-field left down-wind for runway 18, Town and Country traffic.

The aircraft is now entering the traffic pattern. In this example, the aircraft is making a standard 45 degree entry to the downwind leg of the pattern for runway 18. Or, the aircraft could land straight in without entering the typical rectangular traffic pattern. Usually aircraft that are executing an instrument approach will use this method. Examples of a radio broadcast from aircraft that are using this technique are:

For an aircraft that is executing an instrument approach:

Town and Country traffic, Cessna 123 Bravo Foxtrot, is one mile north of the airport, GPS runway 18, full stop landing, Town and Country traffic.

As the aircraft flies the traffic pattern for a landing, the following radio broadcasts should be made: Town and Country traffic, Cessna 123 Bravo Foxtrot, left base, runway 18, Town and Country traffic.

Town and Country traffic, Cessna 123 Bravo Foxtrot, final, runway 18, Town and Country traffic.

After the aircraft has landed and is clear of the runway, the following broadcast should be made: Town and Country traffic, Cessna 123 Bravo Foxtrot, is clear of runway 18, taxing to park, Town and Country traffic.

When an aircraft is departing a non-towered airport, the same procedures apply. For example, when the aircraft is ready for takeoff, the aircraft should make the following broadcast: Town and Country traffic, Cessna 123 Bravo Foxtrot, departing runway 18, Town and Country traffic.

For safety reasons, a remote pilot must always scan the area where they are operating a small UA. This is especially important around an airport. While it is good operating procedures for manned aircraft to make radio broadcasts in the vicinity of a non-towered airport, by regulation, it is not mandatory. For this reason, a remote pilot must always look for other aircraft in the area, and use a radio for an extra layer of situational awareness.

Aircraft Call Signs

When operating in the vicinity of any airport, either towered or non-towered, it is important for a remote pilot to understand radio communications of manned aircraft in the area. Although 14 CFR part 107 only requires the remote pilot to receive authorization to operate in certain airport areas, it can be a good operating practice to have a radio that will allow the remote pilot to monitor the appropriate frequencies in the area. The remote pilot should refrain from transmitting over any active aviation frequency unless there is an emergency situation.

Aviation has unique communication procedures that will be foreign to a remote pilot who has not been exposed to “aviation language” previously. One of those is aircraft call signs. All aircraft that are registered in the United States will have a unique registration number, or “N” number. For example, N123AB, which would be pronounced in aviation terms by use of the phonetic alphabet as, “November One-Two-Three-Alpha-Bravo.” In most cases, “November” will be replaced with either the aircraft manufacturer’s name (make) and in some cases, the type of aircraft (model). Usually, when the aircraft is a light general aviation (GA) aircraft, the manufacturer’s name will be used. In this case, if N123AB is a Cessna 172, the call sign would be “Cessna, One-Two-Three-Alpha-Bravo.” If the aircraft is a heavier GA aircraft, such as a turbo-prop, or turbo-jet, the aircraft’s model will be used in the call sign. If N123AB is a Cessna Citation, the call sign would be stated as, “Citation, One Two-Three-Alpha-Bravo.” Typically, airliners will use the name of their companies and their flight number in their call signs. For example, Southwest Airlines flight 711, would be said as, “Southwest Seven-One-One.” There are a few airlines such as British Airways who will not use the company name in their call sign. For example, British Airways uses “Speedbird.”

To close, a remote pilot is not expected to communicate with other aircraft in the vicinity of an airport, and should not do so unless there is an emergency situation. However, in the interest of safety in the NAS, it is important that a remote pilot understands the aviation language and the types of aircraft that can be operating in the same area as a small UA.