Introduction

Federal regulations that apply to aviation do not cover every situation nor do they guarantee safety. For example, a pilot may legally fly in marginal VFR conditions at night even though low visibility and night hazards increase the risk for an incident or accident. Therefore, pilots should consider non-mandatory self-regulation in the form of personal minimums.

Personal Minimums

Pilots who understand the difference between what is “smart” or “safe” based on pilot experience and proficiency establish personal minimums that are more restrictive than the regulatory requirements. The following six steps allow pilots to establish a set of personal minimums in order to reduce risk and fly with greater confidence.

Step 1—Review Weather Flight Categories

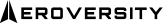

Establishing personal minimums normally begins with weather, and pilots should know the range of ceiling and visibility that defines each category. [Figure 2-1]

Figure 2-1. Weather category values for ceiling and visibility.

Step 2—Assess Experience and Comfort Level

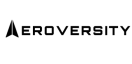

Pilots should also take a few minutes to complete the certification, training, and experience summary in Figure 2-2 by filling in the right column. Some pilots fly different aircraft categories and classes and may develop different personal minimums based on the specific aircraft flown. For example, many pilots will have a different set of personal minimums when flying a single-engine airplane versus a multiengine airplane. Depending on pilot experience, the minimums in a multiengine airplane could be higher than the single-engine airplane minimums. Pilots may use the information entered in Figure 2-2 to set personal minimums for a variety of situations using tables in Figure 2-3, Figure 2-4, and Figure 2-5.

Figure 2-2. Certification, training, and experience summary.

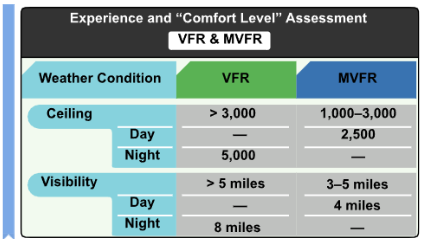

The tables in Figure 2-3, Figure 2-4, and Figure 2-5 layout a sample assessment. Figure 2-3 shows how entries might look in the Experience & Comfort Level Assessment VFR & MVFR table. Suppose a pilot’s flying takes place in a part of the country where clear skies and visibilities of 30 miles or more are normal. The entry might specify the lowest VFR ceiling as 7,000 feet, and the lowest visibility as 15 miles. A pilot may never experience MVFR conditions and would leave the dash in place. However, in this example and as shown in Figure 2-3, the pilot regularly flies in an area where normal summer flying involves hazy conditions over relatively flat terrain and is more experienced and comfortable in MVFR. The pilot used the MVFR column to record personal minimums of a 2,500-foot ceiling and 4 miles visibility for daytime operations.

For night flight, a ceiling under 3,000 feet or visibility less than 5 miles may create an unnecessary risk, so the pilot decided to record a 5,000-foot ceiling and 8 miles visibility in the VFR column.

Figure 2-3. A sample pilot experience and comfort level assessment for VFR and MVFR.

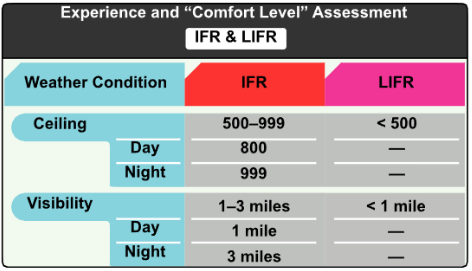

For IFR, Figure 2-4 shows how a pilot recorded the lowest IFR conditions recently and regularly experienced. Although a pilot may have successfully flown in low IFR (LIFR) conditions, it does not mean the pilot was “comfortable” in these conditions. In this example, the pilot did not fill in the LIFR boxes for known “comfort level” in instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) after deciding to avoid flight in those conditions.

Figure 2-4. A sample pilot experience and comfort level assessment for IFR and LIFR.

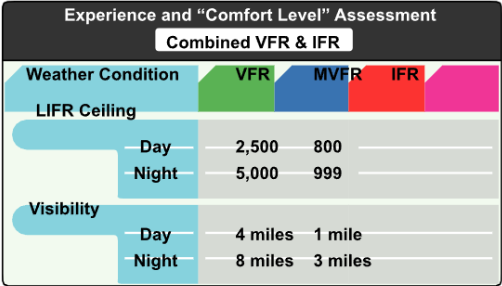

If combined into a single table, the summary of a pilot’s known “comfort level” for VFR, MVFR, IFR, and LIFR weather conditions might appear as shown in Figure 2-5.

Figure 2-5. Experience and comfort level assessment for combined VFR and IFR.

Step 3—Consider Other Conditions

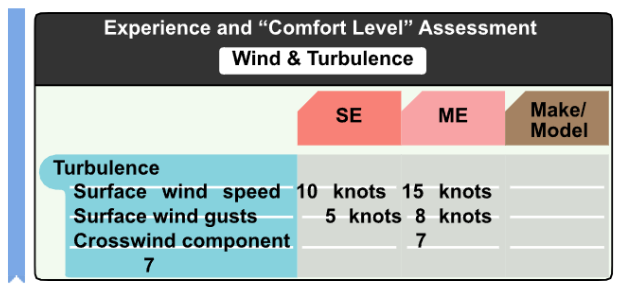

Pilots should also have personal minimums for wind and turbulence and record the most challenging wind conditions comfortably experienced during the last six to twelve months. As shown in Figure 2-6, a pilot may record these values for category and class, or for a specific aircraft.

Figure 2-6. A sample pilot experience and comfort level assessment for wind and turbulence.

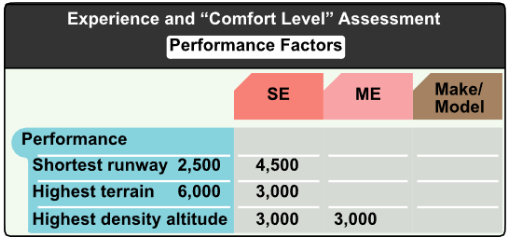

In addition to winds, “comfort level” inventory should also include factors related to aircraft performance. Completing the table with reference to the aircraft type and terrain typical for most flying [Figure 2-7] will establish a safety buffer. If the pilot has never operated an airplane from a runway shorter than 5,000 feet, the shortest runway box should say 5,000 feet.

Figure 2-7. Sample experience and comfort level assessment for performance factors.

Step 4—Assemble and Evaluate

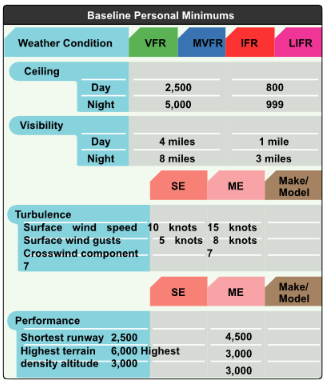

Combining all these numbers results in a baseline personal minimums table as shown in Figure 2-8.

Figure 2-8. Sample baseline personal minimums.

Step 5—Adjust for Specific Conditions

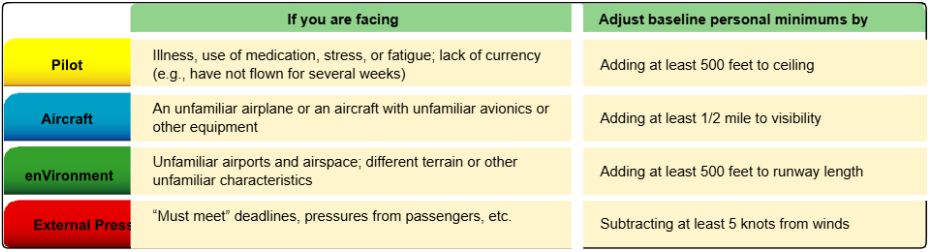

Any flight a pilot makes involves an infinite combination of pilot skill, experience, conditions, and proficiency. Aircraft equipment and performance, environmental conditions, and external influences vary considerably. Both individually and in combination, these factors can compress or expand the safety buffer provided by baseline personal minimums. Consequently, a pilot should develop a practical way to adjust baseline personal minimums to accommodate specific conditions or aircraft.

Note that the example situations and additional safety margins [Figure 2-9] only provide a starting point. Pilots may develop their own adjustment factors based on experience, aircraft capabilities, and operation. If flying experience is limited or infrequent, the adjustment magnitude could increase. If multiple special conditions apply, a pilot could make an adjustment for each factor. For example, suppose a pilot plans a night cross-country flight to an unfamiliar airport, departing after a full workday. The table in Figure 2-9 suggests raising baseline personal minimums by adding 1,000 feet to the ceiling value, one mile to visibility, and 1,000 feet to required runway length.

Figure 2-9. Examples of additional safety margins from baseline personal minimums.

Here are several important cautions regarding personal minimums. The pilot should:

- Not adjust personal minimums to complete a specific flight. The time to consider adjustments is not while under pressure to fly, but rather when time and objectivity permits an honest self-analysis about skill, performance, and comfort level during the last few flights.

- Make adjustments to one variable at a time. For example, if the goal is to lower baseline personal minimums for visibility; the ceiling, wind, or other values should not change at the same time.

- Seek training and consult with a flight instructor before making a significant adjustment to personal minimums.

Step 6—Stick to the Plan

As many pilots know, adhering to personal minimums sometimes creates an ethical dilemma, especially when pressures exist to make a flight. Professional pilots live by the numbers, and so should general aviation pilots. Established personal minimums enable the pilot to make a no-go or divert decision rather than departing with a sense of unease regarding the outcome of a flight. In addition, a written set of personal minimums can also make it easier to explain tough decisions to passengers who depend on the pilot’s judgment.

Using the FAA WINGS Program for Risk Mitigation & Safety

The FAA maintains a safety program that provides courses on a variety of topics as a means to enhance safety. The WINGS Pilot Proficiency Program is based on the premise that pilots who maintain currency and proficiency will enjoy a safer and more stress-free flying experience. As an added bonus, completion of a phase of the WINGS Program can count for a flight review and participants may receive a discount on certain flight insurance policies. Pilots may create an account and watch a WINGS video using the following links:

Chapter Summary

Many GA pilots have freedom to choose when and where they fly. However, this freedom may also lead pilots to situations where lack of proficiency and equipment capability become a factor. Responsible pilots set personal minimums to help reduce the probability of experiencing an encounter that could lead to an incident or accident.

A copy of the charts used in this chapter can be found in Appendix B, Risk Assessment Tools. Pilots are encouraged to copy and use the charts in the appendix or use comparable tools on an electronic flight bag (EFB) before each flight.