As with any aircraft, the ability to pilot a gyroplane safely is largely dependent on the capacity of the pilot to make sound and informed decisions. To this end, techniques have been developed to ensure that a pilot uses a systematic approach to making decisions, and that the course of action selected is the most appropriate for the situation. In addition, it is essential that you learn to evaluate your own fitness, just as you evaluate the airworthiness of your aircraft, to ensure that your physical and mental condition is compatible with a safe flight. The techniques for acquiring these essential skills are explained in depth in Chapter 14— Aeronautical Decision Making (Helicopter).

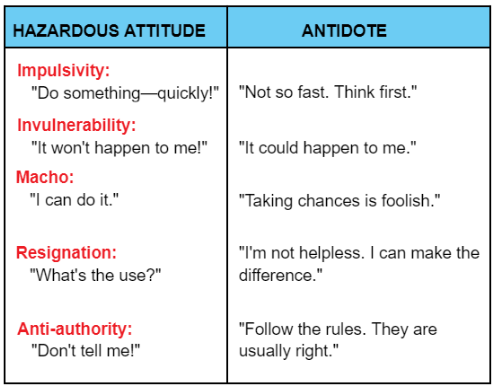

As explained in Chapter 14, one of the best methods to develop your aeronautical decision making is learning to recognize the five hazardous attitudes, and how to counteract these attitudes. [Figure 22-1] This chapter focuses on some examples of how these hazardous attitudes can apply to gyroplane operations.

Figure 22-1. To overcome hazardous attitudes, you must memorize the antidotes for each of them. You should know them so well that they will automatically come to mind when you need them.

Impulsivity

Gyroplanes are a class of aircraft which can be acquired, constructed, and operated in ways unlike most other air- craft. This inspires some of the most exciting and rewarding aspects of flying, but it also creates a unique set of dangers to which a gyroplane pilot must be alert. For example, a wide variety of amateur-built gyroplanes are available, which can be purchased in kit form and assembled at home. This makes the airworthiness of these gyroplanes ultimately dependent on the vigilance of the one assembling and maintaining the aircraft. Consider the following scenario.

Jerry recently attended an airshow that had a gyro- plane flight demonstration and a number of gyroplanes on display. Being somewhat mechanically inclined and retired with available spare time, Jerry decided that building a gyroplane would be an excellent project for him and ordered a kit that day. When the kit arrived, Jerry unpacked it in his garage and immediately began the assembly. As the gyroplane neared completion, Jerry grew more excited at the prospect of flying an air- craft that he had built with his own hands. When the gyroplane was nearly complete, Jerry noticed that a rudder cable was missing from the kit, or perhaps lost during the assembly. Rather than contacting the manu- facturer and ordering a replacement, which Jerry thought would be a hassle and too time consuming, he went to his local hardware store and purchased some cable he thought would work. Upon returning home, he was able to fashion a rudder cable that seemed func- tional and continued with the assembly.

Jerry is exhibiting “impulsivity.” Rather than taking the time to properly build his gyroplane to the specifications set forth by the manufacturer, Jerry let his excitement allow him to cut corners by acting on impulse, rather than taking the time to think the matter through. Although some enthusiasm is normal during assembly, it should not be permitted to compromise the airworthiness of the aircraft. Manufacturers often use high quality components, which are constructed and tested to standards much higher than those found in hardware stores. This is particularly true in the area of cables, bolts, nuts, and other types of fasteners where strength is essential. The proper course of action Jerry should have taken would be to stop, think, and consider the possible consequences of making an impulsive decision. Had he realized that a broken rudder cable in flight could cause a loss of control of the gyroplane, he likely would have taken the time to contact the manufacturer and order a cable that met the design specifications.

Invulnerability

Another area that can often lead to trouble for a gyro- plane pilots is the failure to obtain adequate flight instruction to operate their gyroplane safely. This can be the result of people thinking that because they can build the machine themselves, it must be simple enough to learn how to fly by themselves. Other reasons that can lead to this problem can be simply monetary, in not wanting to pay the money for adequate instruction, or feeling that because they are qualified in another type of aircraft, flight instruction is not neces- sary. In reality, gyroplane operations are quite unique, and there is no substitute for adequate training by a competent and authorized instructor. Consider the following scenario.

Jim recently met a coworker who is a certified pilot and owner of a two-seat gyroplane. In discussing the gyro- plane with his coworker, Jim was fascinated and reminded of his days in the military as a helicopter pilot many years earlier. When offered a ride, Jim readily accepted. He met his coworker at the airport the following weekend for a short flight and was immediately hooked. After spending several weeks researching available designs, Jim decided on a particular gyroplane and purchased a kit. He had it assembled in a few months, with the help and advice of his new friend and fellow gyroplane enthusiast. When the gyroplane was finally finished, Jim asked his friend to take him for a ride in his two-seater to teach him the basics of flying. The rest, he said, he would figure out while flying his own machine from a landing strip that he had fashioned in a field behind his house.

Jim is unknowingly inviting disaster by allowing him- self to be influenced by the hazardous attitude of “invulnerability.” Jim does not feel that it is possible to have an accident, probably because of his past experi- ence in helicopters and from witnessing the ease with which his coworker controlled the gyroplane on their flight together. What Jim is failing to consider, how- ever, is the amount of time that has passed since he was proficient in helicopters, and the significant differences between helicopter and gyroplane operations. He is also overlooking the fact that his friend is a certificated pilot, who has taken a considerable amount of instruc- tion to reach his level of competence. Without adequate instruction and experience, Jim could, for example, find himself in a pilot-induced oscillation without knowing the proper technique for recovery, which could ultimately be disastrous. The antidote for an attitude of invulnerability is to realize that accidents can happen to anyone.

Macho

Due to their unique design, gyroplanes are quite responsive and have distinct capabilities. Although gyroplanes are capable of incredible maneuvers, they do have limitations. As gyroplane pilots grow more comfortable with their machines, they might be tempted to operate progressively closer to the edge of the safe operating envelope. Consider the following scenario.

Pat has been flying gyroplanes for years and has an excellent reputation as a skilled pilot. He has recently built a high performance gyroplane with an advanced rotor system. Pat was excited to move into a more advanced aircraft because he had seen the same design performing aerobatics in an airshow earlier that year. He was amazed by the capability of the machine. He had always felt that his ability surpassed the capability of the aircraft he was flying. He had invested a large amount of time and resources into the construction of the aircraft, and, as he neared completion of the assembly, he was excited about the opportunity of showing his friends and family his capabilities.

During the first few flights, Pat was not completely comfortable in the new aircraft, but he felt that he was progressing through the transition at a much faster pace than the average pilot. One morning, when he was with some of his fellow gyroplane enthusiasts, Pat began to brag about the superior handling qualities of the machine he had built. His friends were very excited, and Pat realized that they would be expecting quite a show on his next flight. Not wanting to disappoint them, he decided that although it might be early, he would give the spectators on the ground a real show. On his first pass he came down fairly steep and fast and recovered from the dive with ease. Pat then decided to make another pass only this time he would come in much steeper. As he began to recover, the aircraft did not climb as he expected and almost settled to the ground. Pat narrowly escaped hitting the spectators as he was trying to recover from the dive.

Pat had let the “macho” hazardous attitude influence his decision making. He could have avoided the conse- quences of this attitude if he had stopped to think that taking chances is foolish.

Resignation

Some of the elements pilots face cannot be controlled. Although we cannot control the weather, we do have some very good tools to help predict what it will do, and how it can affect our ability to fly safely. Good pilots always make decisions that will keep their options open if an unexpected event occurs while flying. One of the greatest resources we have in the cockpit is the ability to improvise and improve the overall situation even when a risk element jeopardizes the probability of a successful flight. Consider the following scenario.

Judi flies her gyroplane out of a small grass strip on her family’s ranch. Although the rugged landscape of the ranch lends itself to the remarkable scenery, it leaves few places to safely land in the event of an emer- gency. The only suitable place to land other than the grass strip is to the west on a smooth section of the road leading to the house. During Judi’s training, her traffic patterns were always made with left turns. Figuring this was how she was to make all traffic patterns, she applied this to the grass strip at the ranch. In addition, she was uncomfortable with making turns to the right. Since, the wind at the ranch was predominately from the south, this meant that the traffic pattern was to the east of the strip.

Judi’s hazardous attitude is “resignation.” She has accepted the fact that her only course of action is to fly east of the strip, and if an emergency happens, there is not much she can do about it. The antidote to this hazardous attitude is “I’m not helpless, I can make a dif- ference.” Judi could easily modify her traffic pattern so that she is always within gliding distance of a suitable landing area. In addition, if she was uncomfort- able with a maneuver, she could get additional training.

Anti-authority

Regulations are implemented to protect aviation personnel as well as the people who are not involved in aviation. Pilots who choose to operate outside of the regulations, or on the ragged edge, eventually get caught, or even worse, they end up having an accident. Consider the following scenario.

Dick is planning to fly the following morning and realizes that his medical certificate has expired. He knows that he will not have time to take a flight physical before his morning flight. Dick thinks to himself “The rules are too restrictive. Why should I spend the time and money on a physical when I will be the only one at risk if I fly tomorrow?”

Dick decides to fly the next morning thinking that no harm will come as long as no one finds out that he is flying illegally. He pulls his gyroplane out from the hangar, does the preflight inspection, and is getting ready to start the engine when an FAA inspector walks up and greets him. The FAA inspector is conducting a random inspection and asks to see Dick’s pilot and medical certificates.

Dick subjected himself to the hazardous attitude of “anti- authority.” Now, he will be unable to fly, and has invited an exhaustive review of his operation by the FAA. Dick could have prevented this event if had taken the time to think, “Follow the rules. They are usually right.”